This University Upheld Its Anti-LGBTQ Policy. Students and Faculty Say It’s Time to Change.

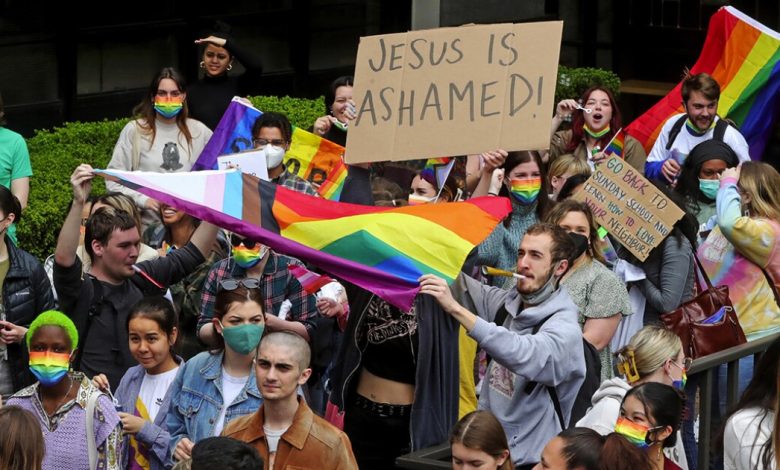

Up until last Friday, if at any point in the day you walked down the hallway toward the president’s office at Seattle Pacific University, you’d see a path littered with sleeping bags, rainbow flags, and water bottles — and anywhere from 10 to 30 student activists.

The students had been there for over a month, protesting an employment policy at the private religious university that they say harms the LGBTQ community.

Now they’ve ended their sit-in and university leaders haven’t changed the policy. But the students are taking a different course of action: They’re considering legal action against the Board of Trustees.

The activists said they plan to file a lawsuit next week, arguing that the board has committed a “breach of fiduciary duty” in light of its insistence on maintaining a policy that requires employees to refrain from extramarital and same-sex sexual activity. As they see it, the policy has negatively affected the university’s reputation and, as such, the reputation of the SPU degrees they will all graduate with.

“The board has chosen to uphold a policy that is out of alignment with the university and that negatively affects our educational opportunities,” organizers wrote on Twitter. “Some students cannot get internships, research funding, or clinical placements. Enrollment is dropping. This policy is detrimental to our campus.”

The potential lawsuit is the most recent development in a months-long standoff over LGBTQ rights at SPU, which enrolls under 4,000 students and is affiliated with the Free Methodist Church of North America. At its June commencement ceremony, dozens of graduating students declined to shake the hand of Pete Menjares, the interim president, as he gave them their diplomas. Instead, they each handed him a small Pride flag. Videos of the protest went viral.

Though organizers concluded the sit-in last week, they’ve left their mark on the space, covering the hallway with 1,080 rainbow paper hearts to represent the 1,080 hours they spent essentially living in the hallway during the sit-in.

“God loves you in a gay way,” they wrote on one of the hearts.

A spokesperson for SPU referred The Chronicle to a letter that Dean Kato, the chair of the Board of Trustees, sent to student organizers on the last day of the sit-in, in which Kato stood behind the board’s decision to maintain the policy and declined to state how individual trustees voted on the matter.

What’s happening at Seattle Pacific University is a striking illustration of growing tensions over LGBTQ rights at religious colleges as their students push back against norms that they consider to be out of touch with a more diverse campus. College leaders, meanwhile, have to balance those demands with the views of board members and alumni who believe it’s crucial for the university to preserve its religious identity.

Months of Activism

Students at SPU have been organizing to improve the treatment of LGBTQ students and employees for years. But the current saga over SPU’s employment policies began in January of 2021, when Jéaux Rinedahl, an adjunct nursing professor, filed a lawsuit against the university for refusing to hire him as a tenured professor because he’s gay.

As is the case at many religious colleges, SPU has a policy in place stating that employees are expected to refrain from “cohabitation, extramarital sexual activity, and same-sex sexual activity.” The school’s statement on human sexuality outlines a similar philosophy, stating that “it is in the context of the covenant of marriage between a man and a woman that the full expression of sexuality is to be experienced and celebrated and that such a commitment is part of God’s plan for human flourishing.”

“Within the teaching of our religious tradition, we affirm that sexual experience is intended between a man and a woman,” the statement reads.

Days after the news of Rinedahl’s lawsuit broke, students and professors protested outside of then-president Daniel Martin’s house to express their support for Rinedahl. The student government at SPU sent a letter to the school’s Board of Trustees calling to replace SPU’s statement on human sexuality with a statement “affirming” the LGBTQ community. Many faculty and staff members joined them with a similar letter.

But last April, the Board of Trustees announced that the statement on human sexuality would remain in place.

That stance doesn’t appear to align with most of the campus community. Shortly after the board’s announcement, 90 percent of all faculty members participated in a vote of no confidence in the board, and 72 percent endorsed it. Hundreds of students, alumni, and others also signed a no-donate pledge, saying they planned to withhold donations to the university until the trustees reversed their decision.

Last fall, students returned to campus to the news that the trustees had commissioned a consulting group to assist with SPU’s culture and policies, among other things. As protests continued throughout the semester, Rinedahl filed a second lawsuit in November against SPU, saying that he applied for a second position at the university that officials did not hire him for and that he had been discriminated against twice. (The university announced this spring that officials had settled the lawsuit.)

In January, the university created a LGBTQ work group made up of professors, trustees, and staff members to evaluate the statement on human sexuality and the anti-LGBTQ employment policy and make recommendations to the board.

The group’s recommendations outlined three options: to maintain the statement on human sexuality and the controversial employment policy; to revise both documents to “affirm” the LGBTQ community; or to remove the mention of “same-sex sexual activity” from the employment policy but keep the mention of extramarital sexual activity. The work group endorsed the third option in its letter and submitted its full report to the board in May.

On May 23, the board once again announced that no changes would be made.

Internal Strife

As a key reason for their decision, the trustees cited a new resolution passed by the Free Methodist Church, which states that any university that changed its employment policies to hire people with a lifestyle “inconsistent with” their teachings on sexual conduct would lose their affiliation with the church.

“While this decision brings complex and heart-felt reactions, the Board made a decision that it believed was most in line with the University’s mission and Statement of Faith and chose to have SPU remain in communion with its founding denomination, the Free Methodist Church USA (FMC), as a core part of its historical identity as a Christian university,” Cedric Davis, the then-chair of the Board of Trustees, wrote in an email to the university community.

The board, though, became mired in internal strife over the decision.

Davis, who was also a member of the LGBTQ work group, resigned from his position as chair three days after the trustees announced they were keeping the policy. Davis declined to comment to The Chronicle. Two other trustees also stepped aside shortly before the vote.

Matthew Whitehead and Mark Mason, both members of SPU’s Board of Trustees and the Free Methodist Church’s Board of Administration, had recused themselves from discussion and voting on the policy. The Chronicle asked an SPU spokesperson to talk with Whitehead and Mason, as well as other trustees, but they were not made available for interviews.

But April Middeljans, an associate professor of English who was a member of the LGBTQ work group and former chair of the Faculty Senate, said in an interview that she believes Whitehead and Mason still influenced the university’s process. She noted the timing of the Free Methodist Church’s resolution on universities, which came shortly before the board’s announcement.

Many faculty members feel that the trustees’ actions violated shared governance, and that “the vote was unduly influenced by the church’s pronouncement,” Middeljans said in an email.

As the power struggle over SPU’s direction continues, a broader question hangs over the debate: Why maintain the university’s affiliation to the Free Methodist Church?

Michael S. Hamilton, a former professor of history at SPU, said in an interview that the push for social change at SPU is best understood in the context of changing student demographics over the past 15 years. When Hamilton first started working there in 1999, the average SPU student was usually white, raised in a suburban evangelical church, and often homeschooled. Today’s student body is much more diverse, he said.

Hamilton, who has researched religious colleges, said SPU doesn’t benefit much — financially or in terms of stature — from its affiliation with the church. Instead, he believes the trustees were using the church to absolve themselves of the responsibility for a fraught decision. That approach, he said, “didn’t involve them in moral or biblical interpretation questions” — and therefore was “the most defensible.”

The church, meanwhile, is balancing a desire to maintain a relationship with SPU because of its academic reputation, Hamilton said, while also trying to appease the more conservative members of the church who don’t like SPU’s more-progressive evolution.

“It is likely that there are Free Methodist leaders who have long lamented SPU’s increasing autonomy and increasing cultural and political liberalism, and are now happy to be able to have their hands on a chain that might yank the school back in a more conservative direction,” he wrote in a follow-up email.

Kevin Neuhouser, a professor of sociology at SPU who was also a co-chair of the LGBTQ work group, said the board might be trying to avoid the “secularization” of SPU.

“From the board’s point of view, it seems that they have a concern that if SPU lost its connection to the denomination that there would be a secularization of the university, that the university would lose its Christian focus and identity,” he said.

Neuhouser said the board tends to be a “self-perpetuating group” — meaning that if a trustee leaves, the remaining members are likely to fill the open spot with a trustee who shares their beliefs. The three trustees who left amid the vote on the employment policy, Neuhouser said, seemed more “open to change.” But their replacements might not be.

Real Consequences

As some on campus see it, the board’s actions have had real consequences for SPU. Lori Brown, the director of the Center for Career and Calling, sent an email to the student body in late May offering advice for how to separate themselves from SPU’s anti-LGBTQ practices as they search for jobs or internships.

Her email recommends that students clarify on their resumes, LinkedIn profiles, or cover letters that they do not support SPU’s anti-LGBTQ policies.

“We’ve had reports of internships/jobs lost or put on hold due to the Board of Trustees decision regarding SPU’s LGBTQIA+ hiring policy,” Brown wrote in her email. “If you have an internship or job offer that has been affected by the board’s decision, we in the CCC are here to help.”

Mishu Alemseged, a graduate student studying at SPU, worked at the Center for Career and Calling until he decided a month ago to leave his job. Alemseged said he plans to finish his degree while distancing himself from the university as much as possible.

He shared his frustrations after resigning from his career-services job on a widely read LinkedIn post. “While the department I worked in and the people I worked with are amazing, the university’s Board of Trustees decided that people like me — queer — were not welcome there,” he said in his post.

Laur Lugos, a recently graduated senior at SPU who has been involved in student organizing efforts, said she and other student organizers have heard anecdotally from other students who have chosen to transfer because of the policy.

Now the student activists, armed with over $36,000 of funds raised via GoFundMe, are gearing up to pursue legal action.

Gilbert Mireles, an associate professor of sociology at Whitman College who has studied student activism at secular and religious colleges, said it can be difficult to prove a breach of fiduciary duty, so the potential lawsuit may be a longshot. But it’s a “sophisticated strategy” for student activists, he said.

“This is not the typical sort of strategy that one sees in student mobilization efforts on college campuses, and certainly I would say it is uncommon at religious institutions,” he said.

Beyond the possible suit, Neuhouser believes campus activism will persist even as some of the student organizers graduate.

Neuhouser is the faculty adviser for Haven, a group for LGBTQ students and allies at SPU. He said when the student organization first tried to become an official club in 2007 — which ended up becoming a six-year-long fight — he would have been excited to hear that even a handful of tenured professors were willing to sign a petition in support of their organization. Today, with an overwhelming majority of professors expressing support for the elimination of the anti-LGBTQ policy, he said there’s been a “sea of change” on campus.

“I’m confident that this momentum is deep-seated enough that it’s not going to evaporate over a summer,” he said.