What Really Goes Into Making the Grade

Across the country, professors teaching first-year students wondered the same thing. Many new students would have to reacclimate to in-person learning and adjust to college at the same time. Some had suffered losses; many were struggling with their mental health. Admissions officers, meanwhile, had a murkier view of these students than they typically would. Freshmen, everyone agreed, had been through a lot. But it was unclear how that had affected their college preparation. Could they do the work?

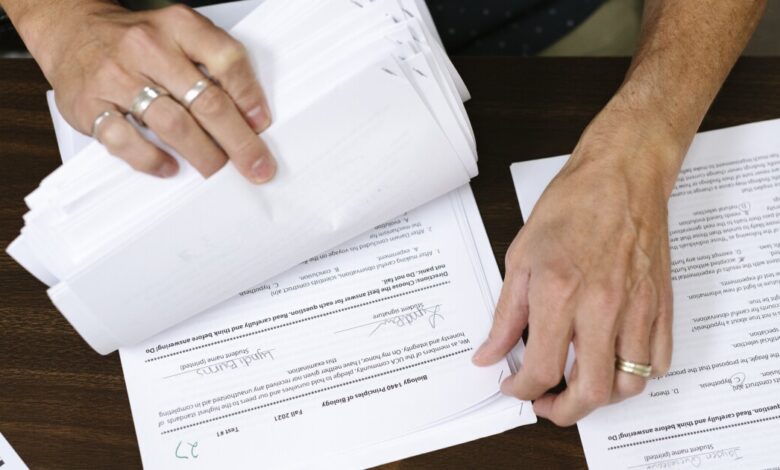

For Padberg, the way students performed on this first test — much of which covered content they should have learned in high school — would provide the first real clue.

When he finished grading, he was relieved. The class average was 78 percent, pretty typical for the first exam. Students in another section of the course taught by his wife, Mita Puri, an assistant professor, had a nearly identical average.

But what did 78 percent really mean? The number didn’t tell the professors how, or why, students seemed to be on track. Had they managed to learn what they needed to at the tail-end of high school? Were they working harder to compensate for this semester’s particular challenges? Were the couple’s extra efforts to support them paying off? Perhaps what mattered most was that the wheels had not come off the bus. Still, Padberg would feel more sure of that when he saw how students fared on the second exam.

Academic performance always contains a lot to unpack. Students’ test scores might be rendered as a nice, clean numeral, but they aren’t some pure measure of students’ understanding. Performance is influenced by what students knew before the course began; whether and how they studied; their confidence; their reading comprehension and test-taking savvy. And it isn’t just about students, either — their performance is also shaped by the way they’re taught.

And that has changed over the past year and a half. Padberg didn’t think the pandemic had put a dent in students’ academic abilities, exactly. But he expected they might feel rusty and face mental-health challenges. He thought they would benefit from some additional direction. So he’s making an extra effort to check in with students, to be personable, and to be clear. “There’s that old thing of: Tell ‘em what you’re gonna tell ‘em. Tell ‘em. And then tell ‘em what you told ‘em,” he says. “I’m trying to put those breadcrumbs down a little bit more.”

Padberg had been excited six months earlier when he’d signed up for in-person teaching. Now, it felt irresponsible, even dangerous. Was the university really moving forward with this? How could he even write a syllabus without being sure which format he’d be teaching in, or what safety measures he could put in place?

Lucy Garrett for The Chronicle

About a week and a half before the semester began, Padberg emailed his department chair. Could classes, he asked, be moved online? “I’m not trying to be a pain,” he wrote, “but we are scientists, and from what we understand about delta’s transmissibility, and looking at the current numbers in our state, in-person instruction truly seems like a horrible (and sadly, potentially deadly) idea at the present time.”

That afternoon, the chair emailed the department. “I know everyone is concerned about the fall semester with COVID,” he wrote. “Here is what I have confirmed. As of this moment, the position of UCA is that all courses that are listed as traditional (i.e. F2F) will still be offered F2F.” In closing, the chair offered to work with professors. “My personal stance is that I want to support whatever instructional method you feel comfortable with while still trying to satisfy the UCA position — we just may need to be a little inventive.”

It looked like in-person instruction would proceed, no matter what. The university would require masks, at least for the time being, but campus Covid mitigation seemed to have moved into do-it-yourself mode. Padberg was surprised at how angry he felt.

Lucy Garrett for The Chronicle

The night before classes began, he and Puri spent the better part of an hour preparing room 102 of the Lewis Science Center, where they’d hold their respective sections the next day. They tested a microphone Puri had borrowed, hoping it would help students in the lecture hall hear her through her mask. They measured the distance between chairs, which varied because of the way the room was laid out. They drew X’s on pink Post-it Notes and affixed them to the back of every other chair so that students would remain distanced even in Padberg’s larger section (Puri started the semester with 56 students). They brought extra masks for any students who came to class without them.

Padberg and Puri hoped they were ready. They didn’t really have a choice.

Lots of students take introductory biology because they want to work in health care, or with animals. They aren’t always prepared to begin by studying cells and things even smaller than cells.

The professors were trying to put the classroom experience back together. But parts of it kept breaking.

And there’s so much to cover. Scientists are gaining new knowledge at a steady clip. Professors debate the tradeoffs between breadth and depth. It’s not a theoretical debate: Students who continue in the course sequence will be expected to build on what they learned in intro. They’ll be expected to demonstrate their knowledge again on the MCAT.

Little by little, higher ed is shedding the weed-out course. The fact remains that students fail out of introductory biology, and they fail following patterns that deepen existing inequities and limit the life experiences scientists can draw on. Many biology instructors now see student success as an important goal, and are making their lectures more interactive and labs more authentic. Student performance, growing numbers of instructors recognize, says something about their teaching. Padberg and Puri were prepared to make an extra push to help this year’s cohort.

Puri is collecting regular feedback from her students about what they’re struggling with. Reading their responses is time consuming, as is adjusting her teaching accordingly. Still, Puri thinks it’s important to know where students are running into trouble. Early in the semester, they agreed: It was chemistry.

She was mildly frustrated to hear it. Students are required to have taken chemistry, though some take the two courses concurrently. They’re not expected to know that much, in Puri’s view, just to have a solid handle on key concepts, like the way water’s polarity allows it to act as a solvent, enabling cells to function and supporting life on Earth.

Puri tries to put herself in the mind-set of a novice. She deploys simple analogies, comparing the way oxygen attracts the shared electrons in a water molecule to a little brother hogging the video-game controller. She has students draw pictures. She explains things she thinks they should already know. Still, some remain confused.

She isn’t sure why. It’s her first time gathering this feedback so she’s not sure whether the pandemic weakened students’ comfort with chemistry. But adjusting to the kind of abstract thinking this course demands, she knows, is a persistent challenge.

Lucy Garrett for The Chronicle

Padberg’s approach is slightly different. He’s focusing less on students’ understanding of the material and more on how their lives are going, something he started doing during remote instruction.

This isn’t English class. Science professors have fewer built-in chances to to ask students how they’re doing, just as people. But Padberg has found the practice helpful. It not only gives him a window into students’ lives, it helps him build community in his classes, despite their size and the awkwardness of wearing masks.

This year, Padberg’s goal is to be welcoming. A spirit of teamwork, he thinks, will encourage students to follow safety procedures and roll with the semester’s inevitable disruptions.

Puri considers this student to be a star: “She may not may not be like making 100 on the tests, but she is so engaged, and responds to questions, and engages in discussion in class.”

Taken aback, Puri told her, “You’re doing great!”

Later, she wished she hadn’t said it in front of other students. She wasn’t sure it had been the right response at all.

The student had looked disappointed. Maybe, Puri thought, she felt like her concerns had been dismissed. So she emailed the student later on. “I wanted to follow up and make sure it’s clear that I am happy to help and I hope to see you in office hours on Thursday morning!” Puri wrote. “I just wanted you to know that you really are doing a really solid job so far, so even if you feel lost sometimes, it seems like you are understanding the important concepts pretty well at least up to this point. But for sure the more we go over everything the more confident you’ll be about the info!”

The student wrote back: “Thank you so much, I really appreciate your encouragement!”

Maybe this group of students is worried about being unprepared. Maybe they’re particularly comfortable asking for help. But there’s no question many of them are making significant adjustments: to college, to learning in person, to learning in person in pandemic conditions.

Lucy Garrett for The Chronicle

It took Padberg and Puri’s students weeks to get used to the hybrid lab schedule, in which two groups alternated attending in person. They weren’t all sure whether their test would be in person, or where to submit assignments.

Puri found herself prompting students to take notes during lecture. She asked if they had a good system for doing so, and not all of them did. She explained, from a neuroscience perspective, why note-taking was helpful.

Padberg gave an even simpler reminder: Pay attention. Sure, students might have been more distracted on Zoom. But their distraction was not as obvious to the person teaching.

Puri had to put her course on the back burner for several weeks early in the term. Her tenure packet was due on September 1. Her father moved, suffered a fall, and had an unrelated operation. She and Padberg made an offer on a house, with the idea that her father would live there, too.

Students’ performance in a course isn’t just about them. They way they’re taught matters, too.

Almost immediately, she was behind on her syllabus, and students began to worry that they hadn’t covered what they would need to know for the first test. She sent an encouraging email: “Be assured,” she wrote, “that everything on the exam is related to what we’ve discussed in class and/or you’ve seen in the chapters!” With so much material to cover in intro biology, Padberg, too, struggled to stay on track.

Then there was the challenge of accommodating students who had to quarantine. Puri had figured she was in good shape — she could give them the short, digestible chunks of her lectures she’d recorded for online teaching the year before. But then she realized those lectures included references to previous terms’ deadlines, labs, and earlier lectures. Maybe they would just confuse students more.

Covid precautions complicated test days, too. Students asked to make up the exam if they had cold symptoms, something they wouldn’t have done before the pandemic. Padberg was all for reducing the risk of illness spreading through his classroom. But every time a student had to make up a test, he realized, he was stuck in his office, and out of his lab, another 75 minutes.

The professors were trying to put the classroom experience back together. But parts of it kept breaking.

Despite everything, the students seem to be hanging in there. They took their second exam — the one that provides a more accurate gauge of how the course is likely to go. Padberg’s students scored about the same as they had in previous years. Puri’s class average was several points higher than his.

It’s too soon, of course, to say if that pattern will hold for the whole semester. If it does, someone looking only at the numbers might see no big difference between how students performed before the pandemic and how they’re doing now.

But things have changed. Most students are happy and excited to be learning in person. Padberg can feel it when he teaches and confirmed it in a bonus question on his second exam. Students said they’re better able to focus, and get help, in the classroom.

And the professors? They’re putting in extra work, and have picked their spots with care.

Academic performance is always tricky to untangle. But when the dust settles on this semester, anyone hoping to make sense of it should keep that energy and extra work in mind. Without it, students might well have scored lower.

Source link