Who Is Native Enough?

When the University of California system announced this spring that it would provide free tuition to any Native American student who belongs to a federally recognized tribe in California, Bauerle’s job became more complicated.

Bauerle was now faced with helping the financial-aid department figure out who among UC Berkeley’s 300 self-identified Native American students belong to a federally recognized tribe, an emotionally fraught process wrapped up in bureaucracy, paperwork, and some activists say, a racist history.

She had three months to do it.

Limiting the scholarship program to members of federally recognized tribes is the only way the UC system can waive tuition for Native Americans without violating the state’s Proposition 209 law, which bars universities from providing special benefits to students based on their race, sex, or ethnicity.

But by taking such a restrictive approach, the university system is effectively excluding thousands of adults who belong to one of the state’s many tribes without federal recognition, are mixed race, belong to multiple tribes, or whose family members have been disenrolled from a tribe.

In the weeks after the announcement, Bauerle was bombarded with emails and phone calls from confused students, parents, and prospective students. There was animosity.

“What about the non-federally recognized tribes?” they asked her.

As administrators struggle to help historically disenfranchised students afford rapidly increasing tuition costs, Bauerle’s experience shows that waiving tuition for a category of racial minorities can be more complicated than it looks, even when universities are explicit about who they’re trying to help.

So far, after scouring copies of tribal enrollment cards and documents, Bauerle and the university’s financial-aid office have managed to identify only 50 students who qualify for their $14,000 tuition to be waived.

It’s still too early to determine how many Native students qualify in the entire UC system. A number of campuses are still processing applications, according to the system’s spokesperson.

Bauerle said she’s conflicted.

On the one hand, she doesn’t want students who are not Native American to try to scam the scholarship program. On the other hand, she said, she doesn’t want Native students to feel like they’re not qualified for the litany of other services the university provides Native American students, question their identity, or feel like they’re not Native enough.

“There are some stereotypes that permeate higher ed that really cause people to question if they’re authentic enough,” she said.

It’s rare for colleges to address disparities in such a race-conscious way.

College administrators have said they have struggled to reverse the lingering effects of explicitly racist laws without being conscious of the ways bias, housing, and other forms of discrimination still affect students’ lives.

Talia Herman for The Chronicle

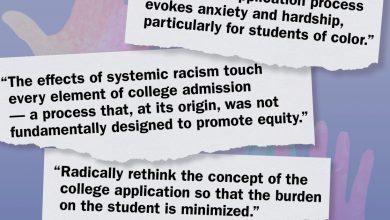

Ignoring race is not the way to fix racism in higher education, according to a 2020 report from the Education Trust, a national nonprofit that advocates for students of color and students from low-income families. In order to have racial equity in higher education, the organization says that institutions should use holistic admissions processes that include race as a factor, and state bans on affirmative action should be removed.

“Racist and race-conscious policies got us here,” said Kayla C. Elliott, director of higher-education policy at the Education Trust. “So it takes race-conscious policies that are progressive, that are affirmative, that are anti-racist, to undo the effects of those laws and those policies.”

But defining the confines of who belongs to which racial category is exceedingly complicated and places administrators in awkward positions.

The free-tuition program for Native Americans belonging to federally recognized tribes has been lauded by national media outlets, diversity advocates, and some Native Americans as a way to boost the measly enrollment of a group of students who struggle more than any other racial group to afford and matriculate through college.

Across the nation, just a quarter of Native students pursue higher education, compared to 41 percent of students over all, according to the Postsecondary National Policy Institute.

The free-tuition program comes at a time when many universities are grappling with the ways their institutions have, in the past, stolen Native land, supported and gained from Native massacres, and prevented Native Americans from enrolling.

But many Native American advocates of non-federally recognized tribes have questioned the program’s actual impact and its methodology.

They say the scholarship program, which costs the system $2.4 million, perpetuates longstanding inequities between Native Americans because there are many historically verifiable tribes that are not yet federally recognized.

For many tribes, federal recognition means financial stability, access to land, health care, and other resources. But that recognition is hard to come by. Tribes must petition for federal acknowledgement from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and meet seven criteria, including a statement of facts establishing that the tribe has been identified since the early 1900s, a copy of the tribe’s membership criteria and government documents, evidence that the tribe has maintained political influence or authority over its members as an autonomous entity from 1900, and more.

Many tribes aren’t on the federal list because of an accident of history and not because of an issue of legitimacy, said Rev. John Norwood, a citizen of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation in New Jersey and the general secretary of the Alliance of Colonial Era Tribes.

Louise J. Miranda-Ramirez, tribal chairwoman of the Ohlone Costanoan Esselen Nation, said that not having federal recognition is like “having to do everything with nothing.”

While she is glad that the UC system is addressing the underrepresentation of Native American students, she said that students who are members of non-federally recognized tribes and already don’t have access to additional financial resources from the government are being left out.

“They’re providing university education to individuals that belong to federally recognized tribes that may have casino money that can afford to go,” Miranda-Ramirez said. “And our kids and young people cannot because there is no money. And that’s what happens with non-recognized tribes.”

For other advocates, the scholarship program is bittersweet.

Non-federally recognized tribes are often forgotten, Norwood said, “sometimes just by accident and ignorance, and sometimes with malicious intent.”

“Even though what they’re offering, ultimately, is aimed at doing good, and I applaud it, the way they are executing it is unjust.”

Of the UC system’s more than 280,000 students, only 1,025 undergraduates and 442 graduate students identify as American Indian. Of these students, the tuition-waiver program is estimated to support 500 undergraduate students and 160 graduate students, according to a UC spokesperson.

For decades, Native American tribal leaders have demanded that UC reconcile and make amends for stealing its land, displacing its people, and collecting more than 10,000 human remains and burial objects in the process, the majority of which now sits in UC Berkeley’s Museum of Anthropology.

In 2018, the system established an advisory council to help determine what to do with the university’s collection. (The university has since repatriated the remains of 49 individuals and more than 40,000 associated funerary objects, according to a university spokesperson.)

Ignoring race is not the way to fix racism in higher education. Institutions should use holistic admissions processes that include race as a factor.

Though the main priority of the advisory council is to ensure that the UC system returns human remains and cultural items back to Native tribes, Bauerle, a member of the council, said they spoke about other ways to make life better for Native students, including a free-tuition program.

Offering Native American students free tuition seemed like a step in the right direction, the committee concluded.

“Native Americans are among the most underrepresented groups within higher education, including at the University of California,” said a university spokesperson in an email to The Chronicle. “The UC Native American Opportunity Plan is part of the university’s larger commitment to expanding diversity and its efforts to make a UC education more affordable and accessible to students of all backgrounds.”

Figuring out how to legally waive tuition for a category of students and then coming up with a verification program were the trickiest parts of the process, Bauerle said.

UC decided to restrict eligibility to students who belong to federally recognized tribes, but it left it up to each campus to determine how to verify this.

The tribal-verification process varies by tribe (there are more than 570 federally recognized tribes in the country), and there are 13 regions in the United States that issue a Certificate Degree of Indian or Alaska Native Blood.

At Berkeley, administrators decided that to qualify, students must provide documentation of tribal enrollment, whether that’s a certification, an enrollment membership card that contains the tribal seal or official signature of a tribal leader, a tribal identification card with an enrollment number, or a Certificate Degree of Indian Blood.

When Bauerle met with officials at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which issues these certificates, she said they told her, “Please don’t send 100 people to our door wanting that CDIB right away because we have limited capacity and they may not get it.”

The UC system president, Michael Drake, met with tribal leaders to see if there was interest in establishing a separate scholarship that would cater to students from non-federally recognized tribes.

In May, the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria announced a $2.5 million scholarship fund for California Native American students from non-federally recognized tribes. “Together, the two programs will allow all eligible CA Native American students to attend with tuition and fees covered.”

To qualify for that scholarship program, students must be members of a non-federally recognized tribe and must provide a Certificate Degree of Indian Blood with a California tribal affiliation or be a descendant of a person with a Certificate Degree of Indian Blood showing a California tribal affiliation.

Of the 23 people who applied for the program across the UC system, 19 were approved, according to a spokesperson for the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria. Two of the applications were denied because they were submitted by members of federally recognized tribes.

Greg Sarris, chairman of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, sees the scholarship as a way that federally recognized tribes can assist those that are not federally recognized.

“It’s impossible to be just and fair in a bad situation that exists because of colonization,” Sarris said. “I just try to do the best I can.”

Previously, students who identified with multiple races would not be considered Native American within the UC system.

They want the new process to recognize tribal citizenship and affiliation. This way, administrators can better identify which students are members of federally recognized tribes, non-federally recognized tribes, or state-recognized tribes, and which claim lineal descent.

It’s impossible to be just and fair in a bad situation that exists because of colonization.

Native American students on campus said how they identify themselves to the university is something they don’t take lightly since the American government has taken extreme measures to erase their identity.

Alexis A. Zaragoza, who is half Cherokee and half Mexican, said she’s wrestled with her identity when it comes to self-identifying on college-related documents. She identifies more with being Native American, so she chose to check just that box on her college application. She said that she knows that if she checks the one saying that she’s Hispanic, she’ll be put solely in that category and not counted as Native American.

“At this point, I only check Native, even though I am Hispanic, because I know that they’re going to group me into Hispanic only,” she said. “And I don’t want that, especially when it comes to representation … I have to make that choice.”

Bauerle said she’s learned of ways to streamline the process for figuring out who’s qualified for the process next year, including providing scholarships earlier in the school year and updating the system’s technology to allow students to upload their Native identification documents.

She hopes others in the UC system become more aware of all the nuances of Native identity.

“When one community pushes for benefits or recognition, I think it will probably have an impact on the universities starting to look at ‘how do you provide more support for education for other communities as well?’”

Source link