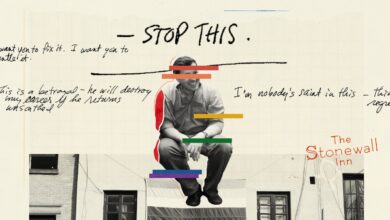

2 Donor Conflicts Reveal Tensions for Jewish-Studies Scholars

[ad_1]

Two years later, the Jaffes stopped giving to Western Washington, apparently because they disagreed with comments that the Jaffe professor, Sarah Zarrow, had made about Israel. The Bernard and Audrey Jaffe Foundation never finished out its pledge.

The situation calls to mind another, more recent donor conflict in the region. Last month, an independent journalist broke the news that the University of Washington returned $5 million to a donor, Rebecca (Becky) Benaroya, after she objected to the Benaroya chair and other faculty members signing a May 2021 public letter. The letter criticized Israeli government actions, said Zionism is “shaped by settler colonial paradigms,” and called the region Israel/Palestine, instead of just Israel. The university decided to refund Benaroya after she wanted to amend her gift agreement to include clauses limiting the political statements the Benaroya chair could make, a university spokesperson said.

The highly unusual return set off a chorus of criticism from academics. “UW programs funded by private donors must not face potential elimination or unstable contingent funding because of a donor’s political demands,” reads a “statement of solidarity” on the University of Washington’s history-department page. “Academic freedom does not only mean permitting scholars to express opinions without institutional reprimands. It also means protecting the ability of faculty, staff, and students to conduct their work.”

The freedom to push boundaries is required for “scholarly excellence,” said David N. Myers, a professor of Jewish history who has an endowed chair at the University of California at Los Angeles.

Together, the University of Washington and Western Washington cases are fresh examples of the ways in which big donors try or expect to exert influence on universities. While donor pressure can happen all across a campus, these cases reveal Jewish studies’s particular vulnerabilities: namely, the third-rail politics of modern Israel and the fact that the field has depended heavily on donors since its founding in the 1970s.

The cases differ in degree. The Benaroya gift was an order of magnitude larger than the Jaffe Foundation pledge, and the University of Washington’s decision to return its gift was unusual, while not finishing pledges is more common.

Either way, however: “It’s certainly a form of exerting power,” said Lila Corwin Berman, a professor of history at Temple University. In her book The American Jewish Philanthropic Complex: The History of a Multibillion Dollar Institution, Berman argues American law gives big-time philanthropists undue influence because charities decide, without public input, what causes to fund, while taking tax breaks that are ultimately subsidized by the public.

A call and email to Larry Benaroya, Rebecca Benaroya’s son, weren’t returned. Reached via the number listed on publicly available tax documents, Jeffery Jaffe declined to answer questions because, he said, The Chronicle serves a higher-ed audience. “You’re pandering to a culture of cancel, and they will directly and immediately reject anything that does not go along with their perception,” Jaffe said. “I’m not buying into that. I’m totally disenfranchised with the higher-education system.”

“I do not speak for the foundation that made the donation. That foundation is no longer in existence,” he added. (After 2019, the IRS no longer listed the Bernard and Audrey Jaffe Foundation as a tax-exempt organization.) “I spoke only for myself,” he said, “and not for the foundation.”

In a sense, however, Jaffe did agree with an academic, in that there are drawbacks to private funding for public universities.

“I believe there should be a law in this country that all state-run institutions should be funded only with public money and should not be allowed to get private donations,” he said.

“If we had a higher education system that was 98-percent funded by the government,” Berman said, “these things wouldn’t happen.”

Steven Garfinkle, a professor of ancient history who led the fund-raising effort for the endowed chair at Western Washington, wouldn’t say what drew the Jaffes to the cause, but he talked about the pitch administrators made to donors generally.

A Western Washington professor of Jewish history was retiring, leaving a gap in a department that’s a major pipeline for K-12 teachers in the state. In the years following the 2008-9 financial crisis, state funding for Western had declined. And administrators argued that education was the best way to combat anti-Semitism, 11 instances of which had been reported on campus in 2016-17.

Zarrow came to Western Washington in 2017, after the university raised money for the position, including from the Bernard and Audrey Jaffe Foundation. She taught courses including “History of the Jews” in different time periods, “History of the Holocaust,” “Women and Gender in Judaism,” and “Jewish Nationalisms.”

In a tax document for the fiscal year ending in March 2016, the Bernard and Audrey Jaffe Foundation reported $400,000 was “approved for future payment” to the Western Washington University Foundation for a “professorship in Jewish studies.” Over the next two years, tax documents listed $100,000 each year as “paid during the year,” with concomitant declines in “approved for future payment” figures. Then, in a tax filing in 2019, there are no more donations to Western Washington.

Those numbers aren’t what the Jaffe Foundation pledged and gave to Western Washington, Garfinkle said, but he wouldn’t say what the correct amounts were. The advancement office declined to confirm numbers.

What happened? Neither Garfinkle nor a university spokesperson would say. Zarrow said Garfinkle had told her that comments she made to a student publication troubled the Jaffes. Garfinkle disputes this. “I do not recall that I ever brought a particular publication or concern to Professor Zarrow,” he wrote in an email. “It was not my responsibility to convey such concerns and I would not have undertaken to communicate them.”

In the story that Zarrow believed was the problem, she was quoted saying she didn’t think Israel was a democracy, because different rules applied to Israeli and Palestinian residents, and that it “makes no sense” to use biblical references to decide modern Israel’s borders. She also talked about how criticisms of Israel can descend into anti-Semitism.

In an interview with The Chronicle, she said she was “a little bit scared” when she first learned the Jaffe Foundation had pulled out of her endowed professorship. “I was scared about my position,” she said. She had only been at Western Washington for one year. She also worried about her position in her community. “That somehow I would be a pariah in the community,” she said. “My husband’s very active in the synagogue. I’m not super active, but I go.”

Things turned out fine. Her salary remained the same, and no one at the university seemed to blame her. The Jaffes were quiet about the end of their donations. In contrast to the situation at the University of Washington, where the professor in question joined months of deliberations between the administration and Benaroya, Zarrow didn’t need to interact with her donors. “I was mostly shielded from the process, which I’m grateful for,” she said.

She wasn’t even sure what happened with the Jaffe Foundation money. Garfinkle said what the foundation had already donated remained in the endowment, which continues to fund Zarrow. Numerous other donations remain in the account. The university is continuing to fund raise.

Zarrow considered herself more fortunate than her colleague at the University of Washington, and yet, she said of her situation: “It’s outrageous.”

“I think that every student who comes though my class, my Jewish-history survey, changes their sense of the history and the present of the conflict,” she said. “They come out realizing different things. It’s not that I’ve changed opinion in one way or the other. I don’t have a sense that students understand my politics. So to have a donor and, potentially, public opinion say: ‘No, what you’re doing in the classroom is poisoning the minds of students,’ it’s an enormous blow.”

In an interview Tuesday, Victor Balta, a university spokesperson, said the university was “committed” to maintaining the Israel-studies program and Halperin’s endowed chair. The remaining gap seems to be significant, however. Worth about $11 million at the time that the university refunded Benaroya, the endowment now has about $6 million in it, comprised of interest not returned to the donor, university matching funds, and other sources, according to a university statement.

Washington draws a percentage of the endowment each year to fund programs. That percentage now represents a smaller number of absolute dollars.

“Absolutely, there’s a gap that we’re looking to make up in the short term, and we’ve got several commitments from the university centrally, from the College of Arts & Sciences, and from the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies,” Balta said.

“I can understand the concern, initially, before any specifics had been outlined,” he said. “Certainly, it took some time, and it’s still taking some time to put all these pieces together.”

Another aspect of the donation return that disturbed onlookers was the fact that a representative from a pro-Israel advocacy group, StandWithUs, participated in discussions that led the university to give the money back to Benaroya. StandWithUs has a more conservative definition of what counts as acceptable discourse around Israel. In an op-ed in 2021, one staffer wrote that anti-Semitism “invariably shadows” anti-Israel activism. (The Anti-Defamation League does not consider “anti-Israel activity” to be always anti-Semitic, but warns about when it crosses the line, or is used as a cover.)

An anonymous source told the journalist Emily Alhadeff that StandWithUs would receive the $5 million instead. StandWithUs wouldn’t confirm whether that was true, but did acknowledge that a staffer attended one of the meetings.

“No one at the meeting was introduced as representing an organization,” Balta said. “In hindsight, we would not have permitted this individual to participate in the meeting, had we known he would be soliciting Mrs. Benaroya.”

Some see groups like StandWithUs as “outside forces, coming in and alighting on the university” and creating conflict, as Myers, the UCLA historian, put it. Myers was Halperin’s doctoral adviser, and started a letter of support for her that ran to 36 pages of signatures.

StandWithUs sees itself as supporting donors’ rights and pre-existing intentions. “We do not seek out donors on this issue,” Roz Rothstein, StandWithUs’s co-founder and CEO, wrote in an email. “We educate about this issue, and that leads donors to learn about us and reach out to us to seek guidance.”

In a series of op-eds, StandWithUs leaders framed the purpose of college gifts as fighting what they see as anti-Semitism. They recommended donors structure their gifts so that they pay out slowly over time, allowing donors to stop giving at any time, as the Jaffe Foundation did. Leaders suggested language for gift agreements that specifies what ideas and causes supported programs can’t promote, such as the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement, with donors getting to define “promote.”

That isn’t quite the right way to think of university donations, Myers said. “If you want to support, as I think some donors do, a platform of advocacy for Israeli government policy, there are ways to do that,” he said — not at the university.

Perhaps the Jaffes learned that lesson. After the Bernard and Audrey Jaffe Foundation stopped giving to Western Washington, and before its shuttering, it made one grant, of $29,000, to StandWithUs Northwest, according to tax documents. (StandWithUs did not advise the Jaffe family about its endowed professorship, and the donation was unrelated to Western Washington, Rothstein wrote in an email.) The other donations the foundation made that year were to the Boys & Girls Clubs of Whatcom County and Birthright Israel.

[ad_2]

Source link