4 Ways a Settlement Could Change the Housing Industry

[ad_1]

In the early hours of Friday morning, the National Association of Realtors agreed to a global settlement deal that would resolve several lawsuits against the trade group.

A group of Missouri home sellers sued N.A.R. over their policies on agent compensation, arguing that a N.A.R. rule requiring home sellers to pay commissions to their agents and the agents of their buyers led to inflated fees and price fixing. The lawsuit also called into a question another rule requiring agents to list homes on N.A.R.-affiliated databases in order to sell them. In October, a jury agreed that both practices were anticompetitive, and a judge ordered damages of at least $1.8 billion.

More than a dozen copycat cases, all accusing N.A.R. of stifling competition and violating antitrust laws, have followed.

With the settlement agreement, N.A.R. will pay $418 million in damages, but more important, it has agreed to rewrite a number of rules that have long been central to the U.S. housing industry. Here’s how things stand to change, pending court approval.

Home prices will drop.

In the United States, most agents specify a commission of 5 or 6 percent, paid by the seller. That means that someone with a $1 million home should expect to spend up to $60,000 on real estate commissions alone, with $30,000 going to his agent and $30,000 going to the agent who brings a buyer. Even for a home that costs $400,000 — close to the current median for homes across the United States — sellers are still paying around $24,000 in commissions, a cost that is baked into the final sales price of the home.

With the settlement agreement, sellers’ agents will no longer be required to make offers of commission to buyers’ agents, a practice called decoupling. This will save homeowners billions.

“Decoupling will allow commissions to be removed and negotiated down, lowering both housing prices and overall consumer costs,” said Steve Brobeck, the retired executive director of the Consumer Federation of America. Mr. Brobeck said that Americans spend about $100 billion a year in real estate commissions, and with the settlement, that number is expected to dip by at least $20 billion and up to $50 billion.

Since commissions are tacked onto the price of a home, “Over time, both sellers and buyers will force rates down through negotiation and comparison shopping in a more price-transparent marketplace,” he said.

The 6 percent commission will cease to be the norm.

The lawsuits argued that N.A.R., and brokerages that required their agents to be members of N.A.R., had set rules that led to an industrywide standard commission of 5 or 6 percent — one of the highest rates in the world. Without that guaranteed rate, agents will now most likely be forced to lower their commissions to compete for business.

“U.S. commissions are unlikely to decline to the 1 or 2 percent rate level in England, where only one agent and an attorney are usually involved in a home sale. But they certainly will decline substantially, and commissions will also increasingly reflect the competence and efforts of agents on sales,” Mr. Brobeck said in an email.

Steering — the practice of agents directing buyers to more expensive houses — will be less common.

Most of the databases where homes are listed for sale in the United States are restricted to dues-paying members who belong to N.A.R., a dominance that has led to antitrust allegations against N.A.R.

One N.A.R. rule demands that a listing agent, when posting a home on the database, clearly state the amount of compensation that a buying agent will receive should they bring a buyer. This is a practice that critics say has long led to “steering,” in which buyers’ agents direct their clients to pricier homes in a bid to collect a bigger commission check.

Under the settlement, any fields displaying broker compensation will be eliminated entirely, which will help damper the practice.

About one million real estate agents could leave the profession.

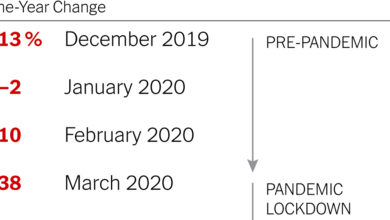

The number of real estate agents swelled during the pandemic, when mortgage rates plummeted and the housing market boomed. In 2020 and 2021, more than 156,000 people got their real estate licenses, and membership in the National Association of Realtors hit a peak of 1.6 million members in 2022.

A lot of that growth was predicated on the idea of easy money.

But now a lot of those agents are struggling, and a reduction in commission rates will only increase the pain. Half of the agents in the country sold one house — or no houses at all — last year. With the industry now staring down a massive overhaul, veteran agents predict their less experienced peers will leave the field all together.

Some analysts predict a mass departure. One widely cited report from investment banking firm Keefe, Bruyette & Woods projects 1 million agents leaving the field as shared commissions vanish.

“Veteran agents have built strong relationships, established reputations and extensive networks. Newer real estate agents may struggle,” said Jen McDonald, who leads LPT Realty in Reno, Nev., and has spent 24 years in the industry. “Without established reputations or strong clients bases, they are going to find it challenging to retain clients or attract new ones.”

[ad_2]

Source link