A Human-Rights Leader Was Denied a Harvard Post Over Alleged ‘Anti-Israel Bias.’ Now a Dean Faces Calls to Resign.

[ad_1]

Harvard University is under fire over accusations that a dean rejected a proposed fellowship for Kenneth Roth, once the longtime executive director of Human Rights Watch, over the organization’s supposed “anti-Israel” stance.

Faculty members and free-speech organizations, alike, have condemned the denial — which was first reported by The Nation last week — as an assault on academic freedom. “Scholars and fellows have to be judged on their merits, not whether they please powerful political interests,” the American Civil Liberties Union’s executive director, Anthony D. Romero, said in a statement condemning the decision. Hundreds of Harvard students and alumni have called for the resignation of Douglas Elmendorf, dean of the John F. Kennedy School of Government, The Boston Globe reported.

A Kennedy School spokesperson said in an emailed statement that Elmendorf “decided not to make this fellowship appointment, as he sometimes decides not to make other proposed academic appointments, based on an evaluation of the candidate’s potential contributions to the Kennedy School.”

Roth told The Chronicle in an email that “it wasn’t our non-existent ‘bias’ that led Elmendorf to veto my fellowship. It was fear of giving Harvard’s imprimatur to our impartial criticisms of Israel.”

Recruited, Then Rejected

In April, Roth announced that he planned to step down from Human Rights Watch, an organization he had led for nearly 30 years. Under his guidance, the group transformed from an “obscure shoestring network of a few scattered offices into a well-financed organization that reports on rights abuses globally,” according to a New York Times article that details Roth’s reign. It described him as an “unrelenting irritant to authoritarian governments.”

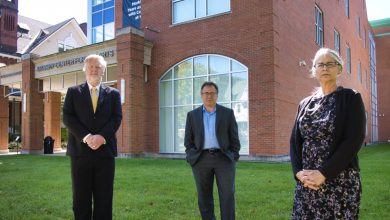

In Roth’s impending departure, the Kennedy School’s Carr Center for Human Rights Policy saw an opportunity. The center soon recruited Roth for a fellowship “because he is one of the most distinguished human-rights leaders of our time,” the center’s director, Mathias Risse, told Carr Center community members in an email on Saturday. (Risse provided the email, which was reported by other media outlets, to The Chronicle.)

After some conversation, Roth and the center “came to an understanding” on what a fellowship would involve, and the center submitted the proposal to Elmendorf’s office for approval “not expecting any difficulties,” Risse wrote in his Saturday email.

But difficulties arose. According to Roth, who wrote about this saga in The Guardian, he met with Elmendorf to introduce himself. The half-hour conversation was pleasant until Elmendorf asked Roth if he had any enemies.

“It was an odd question. I explained that of course I had enemies. Many of them,” Roth wrote. He told the dean that he’d been sanctioned by the Chinese and Russian governments and was hated by Rwanda’s and Saudi Arabia’s regimes. “But I had a hunch what he was driving at, so I also noted that the Israeli government undoubtedly detests me, too,” Roth wrote.

Two weeks later, Roth’s fellowship was dead in the water. Kathryn Sikkink, a professor of human-rights policy at the Kennedy School who is affiliated with the center, told The Nation that the dean’s explanation was that Human Rights Watch has an “anti-Israel bias,” and the outlet reported that “Roth’s tweets on Israel were of particular concern.”

Sikkink told The Chronicle in an email that the dean had shared this reasoning at a small meeting with her, Carr Center leaders, and a staff person in the dean’s office. Risse echoed this account in emails to The Chronicle. “The point wasn’t so much that Doug Elmendorf thought that, but that ‘some people in the university’ who mattered to him did,” Risse said. (Explaining the decision, to the extent that he could, to Roth was “one of the lowest moments in my professional life,” Risse wrote in his Saturday email.)

Elmendorf’s office did not respond to an email or a voicemail message from The Chronicle.

The dean is advised by a 16-member executive board, described on the Kennedy School’s website as “a small group of business and philanthropic leaders who serve as trusted advisors to the Dean and are among the most committed financial supporters of the School.” A handful of those board members have ties with Israel, The Nation reported.

“Several major donors to the Kennedy School are big supporters of Israel,” Roth wrote in The Guardian. “Did Elmendorf consult with these donors or assume that they would object to my appointment? We don’t know. But that is the only plausible explanation that I have heard for his decision.”

The Kennedy School’s website says that its funders “do not control the way we carry out our work.”

The Kennedy School spokesperson said in an emailed statement that, “We have internal procedures in place to consider nominations for fellowships and other appointments, and we do not discuss our deliberations about individuals who may be under consideration.”

The Aftermath

Both Roth and Human Rights Watch have been accused of being hostile to Israel. In 2009, the organization’s founder wrote in a New York Times op-ed that its recent work was “helping those who wish to turn Israel into a pariah state.” In 2014, a tweet from Roth drew criticism from Jeffrey Goldberg, then a correspondent at The Atlantic and now its editor in chief, for, in Goldberg’s words, blaming the Jewish state “for the violent acts of anti-Semites.”

More recently, in 2021, Human Rights Watch issued a report positing that in order to “implement the goal of domination, the Israeli government institutionally discriminates against Palestinians,” and that the government’s actions ultimately amount to the crime of apartheid.

The American Jewish Committee deemed the report a “hatchet job” and “only the latest chapter in an anti-Israel campaign by the once reputable watchdog group.”

Defenders of Roth and Human Rights Watch point to the organization’s ample criticism of other governments, including of Palestinian authorities. Its reporting sets standards in the field, and political scientists who study these matters “confirm the fairmindedness of their reporting,” Risse said in his Saturday email to Carr Center community members.

Roth told The Chronicle in an email that Human Rights Watch is not “anti-Israel.”

“I recognize that there is a cottage industry of groups out there, all with deceptively neutral sounding names, who like to pretend that Human Rights Watch is ‘biased,’” he wrote. “This is rich coming from groups that never criticize the Israeli government for any human rights violation and attack anyone who has the audacity to criticize Israel.”

News of Roth’s denied fellowship rocketed across academe. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression urged Elmendorf to reconsider. PEN America said in a statement that the denial “raises serious questions about the credibility of the Harvard program itself.”

Former Harvard president Lawrence H. Summers tweeted that while he “loathe[s]” Roth’s views on Israel and thinks some of his statements “border on anti-Semitic,” he also thinks it’s correct for FIRE to “seriously question” the decision to deny him a fellowship.

For Roth, the issue is bigger than himself. “Being denied this fellowship will not significantly impede my future,” he wrote in The Guardian. “But I worry about younger academics who are less known. If I can be canceled because of my criticism of Israel, will they risk taking the issue on?”

Risse, the Carr Center’s director, is also concerned about the broader implications. He told The Chronicle in an email that he hopes for some acknowledgment that the wrong call was made and for a commitment to human-rights work at Harvard “that makes it possible for us to remain a credible actor in this domain.

“The current situation,” he said, “undermines our ability to be such an actor.”

[ad_2]

Source link