As Race Looms Large, College Trustees Remain Mostly White

[ad_1]

The report, “Policies, Practices, and Composition of Governing Boards of Colleges, Universities, and Institutionally Related Foundations,” builds on data the group has gathered since 1969, when board members were “97 percent Caucasian” and only 12 percent female. In 2020, nearly 80 percent of board members at private colleges were white, and 64 percent were men, the association found. At public colleges, nearly 65 percent of trustees were white, and 63 percent were men.

Since 2015, when the association last gathered data on board composition, racial and ethnic diversity has improved somewhat on college governing boards. The 2020 figures represented a 6.2-percentage-point increase in such diversity of board members at public colleges, where 30 percent were minorities, and a 3.6-percentage-point increase at private institutions, where 17 percent were minorities.

Still, board diversity has not kept pace with the increasing diversity of students, the association reported. “As with gender, the current racial and ethnic breakdown on boards clearly does not — and has not for decades — reflect the college-student population that governing boards ultimately serve,” Lesley McBain, the group’s director of research, said in a news release.

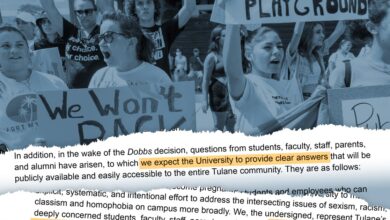

The association’s findings add context to some of higher education’s most significant story lines of recent years. As the nation’s increasingly diverse student populations push for changes on their campuses, they have often found themselves at loggerheads with board members who collectively reflect the demographics of a less-inclusive era.

The disparity between the diversity of college governing boards and the campuses over which they have authority came into sharp focus this past summer at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In a contentious debate over whether Nikole Hannah-Jones ought to be granted tenure at Chapel Hill, the campus’s mostly white trustees had the final say. The board ultimately decided by a split vote to grant tenure to Hannah-Jones, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and lead author of The New York Times Magazine’s “1619 Project,” which situates the nation’s history in the context of slavery. The board only acted, however, when its earlier refusal to vote on the matter fueled national outrage.

The case highlighted what to many observers appeared to be a double standard applied by the trustees. Hannah-Jones had been hired as the Knight chair in race and investigative journalism. Without any attendant public controversy, Chapel Hill had granted tenure to its previous Knight chairs, who were white, but the same was not true for Hannah-Jones, who is Black. (By the time the board got around to voting, Hannah-Jones had had enough, deciding instead to accept a tenured position at Howard University, a historically Black college.)

As the Association of Governing Boards report notes, about 41 percent of public-college students are minorities, compared with 30 percent of board members. At Chapel Hill, the campus’s student-body president, Lamar G. Richards, played a critical role in forcing trustees to vote on the Hannah-Jones tenure case, by formally requesting a special meeting. Richards, who is Black, is a voting trustee by virtue of his office. (In 2020 about 45 percent of public-university governing boards included a voting student representative, according to the association’s report. Less than 8 percent of private colleges had a voting student member.)

In its report, the association noted that public-university boards appear even less diverse when minority-serving institutions are not counted. When focused only on the boards of public colleges that are not categorized as minority-serving, the association found that minority representation fell by about 10 percentage points, meaning just 20 percent of board members were minorities.

Leaders of the University of South Carolina, for example, recently commissioned an exhaustive report on the institution’s historical ties to racism. A Chronicle investigation, however, found that leaders on the Columbia campus had no intention of acting on the commission’s recommendation to remove from 11 campus buildings the names of people who were known to have held racist views. Doing so, under state law, would have required the (unlikely) approval of South Carolina’s majority-Republican legislature. Still, professors have questioned whether the university is as committed as it says it is to diversity and inclusion.

Members of public-college boards are often appointed through a political process, including gubernatorial appointments that require legislative confirmation. That gives public-college board members little power to shape the racial and ethnic diversity of the board, as they do not have direct control over the selection of new members. This helps explain why only half of public-college boards say they are working to improve diversity, according to the association’s report.

On the other hand, 95 percent of private-college boards say they are trying to diversify their membership. That said, only 31 percent of private-college boards say they have a diversity, equity, and inclusion plan, the association reported.

At Kenyon College, a private liberal-arts institution in Ohio, 17 percent of the board’s members are people of color, said Sean M. Decatur, the college’s president. When the board tapped Decatur to lead the college, in 2013, he was the first Black person to hold the job. The board is now slightly less diverse than the student body, he said.

Diversifying the Kenyon board, Decatur said, has been a longstanding goal that predates his presidency, and the trustees will need to become more diverse as the campus does so, he said. Kenyon has intentionally reduced its board’s size in recent years, to 35 trustees from about 43, to improve board engagement, Decatur said. In so doing, the board was clear that reducing its size “could not come at the expense of continuing to increase diversity,” Decatur said.

Like many college presidents, Decatur spoke out after the murder of George Floyd, in 2020. As he watched the video of Floyd’s death at the hands of police officers, Decatur said, “my deep sadness was exceeded only by my powerful anger.”

As the college grappled with how to practically and emotionally navigate the racial reckoning Floyd’s death and others provoked, Decatur saw a reflection of the diversity of lived experiences on Kenyon’s board. The board’s membership included those who, like him, “have encountered and dealt with these issues for a lifetime,” and “folks on the other end of the continuum, who do not necessarily have direct personal experience with these issues and are struggling to understand what the substance of the issues are.”

Selecting a president is arguably a board’s most important job, and white men remain dominant in these leadership roles. Nearly 70 percent of private-college presidents are white, and 66 percent are men, the association found. (At public colleges, the report says, 65 percent of presidents are white, and 77 percent are men.)

In his time at Kenyon, Decatur has seen the ranks of African American college presidents grow, albeit slowly. He said he had not found that the board, in hiring him, became complacent on the work of racial equity. Nor has the campus.

“I find that less of a danger,” Decatur said, “than at times high expectations that a Black president can fix things that haven’t been fixed in the past 200 years.”

[ad_2]

Source link