Bots Are Grabbing Students’ Personal Data When They Complete Assignments

The list of true/false questions posed to the 31-year-old were intimate: Did he have more than one sexual partner? Did he use a latex condom, or oil-based lubricants? Did he use alcohol in “sexual situations”? Had he been vaccinated for Hepatitis B, or HPV? Did he regularly perform genital self-examinations?

It read like a health-clinic intake form. But it wasn’t. It was an assignment for a gen-ed health-and-fitness class he was taking asynchronously online through Bowling Green State University in the fall of 2022 — using McGraw Hill Connect courseware.

“It wasn’t enjoyable. It made me constantly want to lie,” said Blaisdell, who’s in the university’s commercial-aviation program. Blaisdell, who sent various screenshots to The Chronicle, guesstimated upward of 80 percent of the assignments in that class asked similarly personal questions, and included risk assessments for alcohol-use disorder, mental-health disorders, and skin cancer. None, to his surprise, offered any assurances as to how such sensitive information would be handled.

“Whatever I put in,” he recalled thinking, “nobody’s going to take care of the information.”

Millions of learners purchase courseware products like Connect, Pearson MyLab, and Cengage MindTap every year to gain access to integral parts of their college courses, including eBooks, homework assignments, exams, and study tools. But as widespread as courseware has become, safeguards to protect student data privacy are riddled with cracks — a weakness that plagues many educational technologies used in colleges.

The way many students sign up for courseware, to begin with, creates a gray area within the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act — the decades-old federal law known as Ferpa — which governs third-party use of student data. Publishers’ privacy notices, which outline when and how that information is used, are often full of vague and jargon-filled language that make them hard to understand. The hidden world of web tracking, too, is so esoteric that companies with access to student data may, in fact, disclose private details unintentionally.

All of those cracks, privacy advocates say, leave students vulnerable to having their data used and shared in ways they have no knowledge of, or control over.

Institutions aren’t “letting the wolf into the henhouse”; instead, “we’re letting the hens out into a forest of wolves,” said Billy Meinke, an open educational resources technologist with the Outreach College at the University of Hawaii-Manoa who’s done research on publisher misuse of student data.

Such concerns may well have merit: In an analysis of two student courseware accounts, The Chronicle identified instances of student data-sharing that conflicted with, or raised questions about, the practices relayed in publishers’ privacy notices. Most notably, in a review of Pearson MyLab, personally identifiable information, such as a student’s name and email, were sent to Google Analytics, along with notifications of what the student was reading and highlighting in their eBook.

For some, living under the microscope of entities like Google may seem like an inescapable trade-off for using the internet. A social contract of sorts. (The Chronicle also uses Google products; you can read about that in our privacy policy.) But privacy advocates draw a hard line between someone who is surfing the web and a student who is paying to get an education.

“We behave differently if we know we’re being watched. We get timid, we get shy, we spend a lot of our cognition on what people are going to think. … That’s not what we want” in higher ed, said Dorothea Salo, a teaching faculty member at University of Wisconsin at Madison’s Information School. This is especially the case in today’s political climate, where exploring topics like gender identity and abortion can put people in danger.

On principle, too, Salo sees it as colleges’ job to protect students from harm. Publishing companies aren’t impervious to data breaches; for example, McGraw Hill suffered a breach, reported in 2022, that compromised hundreds of thousands of students’ email addresses and grades. (A spokesperson for the company wrote in an email that the vulnerability was quickly remediated, and that “there was no unauthorized access” or exfiltration of the data found.)

“We are supposed to be looking after the well-being and welfare of our students,” Salo said. “That definitely includes taking care of them in ways that would not occur to them.”

In the majority of cases where an instructor — even a group of instructors — adopt a courseware product for their classes, there’s no signed contract or memorandum of understanding. And except in scenarios where an instructor has laid out an alternative, students either have to check the box agreeing to the publisher’s privacy notice and terms of service, or not take the class.

“You’re basically compelling students as part of the curriculum to establish a data relationship with a third-party vendor” in which they have no leverage to negotiate better privacy protections, said Mark Williams, a partner with the law firm Fagen Friedman & Fulfrost LLP who specializes in tech procurement and student data privacy. “I’ve got a lot of problems with that approach.”

Sam Green for The Chronicle

While not all publisher privacy notices are created equal in their scope and detail, they typically offer only a small window into how these companies — and the often nebulous groups of “affiliates” they work with — collect, handle, and share data as students use their products. (Data-privacy advocates acknowledge that this practice is not unique to publishers.)

The language, as Williams put it, can be “pretty plain vanilla,” and ambiguous. Take phrasing around personally identifiable information, often referred to as PII.

“We will … process your PII to meet our legitimate interests, for example to improve the quality of services and products,” McGraw Hill’s end-user privacy notice reads. Andy Bloom, chief privacy officer at McGraw Hill, clarified that processing means “anything that you can really do” with data, including collection, handling, storage, and use.

That’s “a place where I need to change” the notice “to make it better,” he said.

In Pearson’s digital-learning-services privacy notice, too, its proffered definition of PII — ”information personally identifiable to a particular User” — is striking in its brevity, given the increasingly deft and unconventional strategies tech companies use to identify individuals online, wrote Pegah Parsi, chief privacy officer at the University of California at San Diego, in an email.

Most new laws she’s observed, in any sector, count PII as information that could be “reasonably associated with” individuals, too, as well as those in their households, she wrote.

Advocates also noted language in the notices that read like loopholes, or that appeared to omit critical details. A notable one involved the sale of PII. Pearson’s notice says that the company “does not sell or rent User Personal Information collected or processed through the Services,” while McGraw Hill’s notice states, “We will not sell PII to other organizations.”

You’re basically compelling students as part of the curriculum to establish a data relationship with a third-party vendor.

Does “sell” refer only to monetary exchanges? Does that mean that data the publishers have deemed to be de-identified can be sold, without restriction?

A spokesperson for Pearson wrote that its privacy notice applies “the appropriate definitions for the jurisdictions in which our products are sold.” It did not respond to The Chronicle’s questions about specific statements in the notice. Bloom, at McGraw Hill, said that exchanging data falls under the “sell” umbrella, and emphasized that the company “does not use end-user data for anything other than educational purposes.”

Referring to Blaisdell’s doubts around whether his sensitive information is being protected, a McGraw Hill spokesperson wrote in a statement that instructors using Connect “can choose a ‘privacy option’ on assignments such as these, which give students the ability to opt out of their responses being stored. They can also choose a ‘responses saved’ option so responses are saved in aggregate for the instructor.” The spokesperson added that the company employs “sophisticated, cryptographic encryption” for data it stores.

Cengage has perhaps one of the more transparent privacy notices; it details different categories of PII collected depending on the product or service, for example. The Chronicle was unable, however, to identify in the notice any restrictions Cengage has in place for other third parties who have access to students’ PII through its products.

The Chronicle asked Cengage for clarification, but didn’t receive a response. (The company is facing a recent lawsuit that, while not courseware related, claims the publisher’s online videos send visitors’ personal information and video-watching behavior to Google.)

To be sure, there are some consumer-privacy laws that extend into higher ed. Vendors have to comply with the international General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) if serving a student who, while enrolled in a U.S. college, resides in the European Union, where privacy laws are stricter. A handful of U.S. states also have active comprehensive privacy laws, including California, which requires vendors to — among other things — publicly share categories of customer information they’ve sold or shared in the last 12 months.

Those laws, however, are not universal protections for all U.S. college-goers.

For the most part, state legislative agendas concerning data privacy often focus solely on elementary and secondary education. According to the nonprofit Data Quality Campaign, just two of the 15 state-level privacy bills it monitored during the 2022 legislative session included provisions that applied to postsecondary students and institutions.

Federal law has its own limitations. Ferpa was enacted in 1974, predating even the earliest versions of the internet. One of its key purposes is to regulate how third parties use student data as they perform services for an institution that receives federal aid. Traditionally — and especially in cases where a formal contract is involved — these third parties operate under the “school official” exception, allowing them access to students’ PII and education records in the absence of direct consent from each student. This access comes with guardrails, including conditions for when PII can be disclosed to additional parties, and how to handle de-identified data.

But what if the institution isn’t really involved? In many cases, individual instructors adopt and assign courseware to students without a formal approval process — not because they don’t care about protecting students, Salo said, but because data privacy may just not be on their radars. Regardless, that approach raises questions about control: Once students set up an account with the publisher, is data subsequently provided still data that the university “maintains”? Who decides the ground rules, in the absence of a contract?

For Parsi, at UC-San Diego, there’s the rub. Ed-tech vendors, like courseware providers, “are in a strange place where multiple laws apply, and not all of them very clearly,” she said. “People just don’t quite know, and I don’t think it’s about turning a blind eye to it. It just … doesn’t come up.”

That doesn’t mean some vendors are flagrantly skirting federal law, noted Williams, the data-privacy lawyer. Rather, in the absence of clarity, some vendors may think they don’t need to hold themselves to the “school official” exception. Rather, they may consider themselves as having met the “consent” threshold within Ferpa when a student checks the box of a click-through agreement. In that case, the law is significantly less clear on what guardrails apply.

Students in those scenarios “have the least amount of protections,” he said. “College administrations need to get their head more into the game. … They need to be a more robust presence in arranging contracts with these vendors that protect students, and don’t leave them to the murky provisions of Ferpa. That’s how I look at it.”

Bloom, at McGraw Hill, said contract or not, the company considers itself a “school official” under Ferpa (he referred The Chronicle to its terms of service). Even so, its read on one provision, in particular, made Williams pause, and highlighted how companies and individuals alike may be interpreting the law differently.

Asked how long McGraw Hill retains users’ PII before deleting it, Bloom stated that, under Ferpa, the company can never delete data without a student’s or college’s explicit request. When it comes to students’ data, “the institution is the controller,” Bloom said.

Williams fundamentally disagrees. “If the question is whether a vendor is required to delete data after its use is no longer required … my answer is yes,” he said. “You don’t get to keep the data forever until someone tells you to get rid of it.”

Pearson and Cengage did not respond to specific questions about how they define themselves under Ferpa. Pearson’s privacy notice does say it complies with “applicable provisions” of Ferpa “as a school official.” Cengage’s notice refers to operating in ways “required” or “permitted” by law.

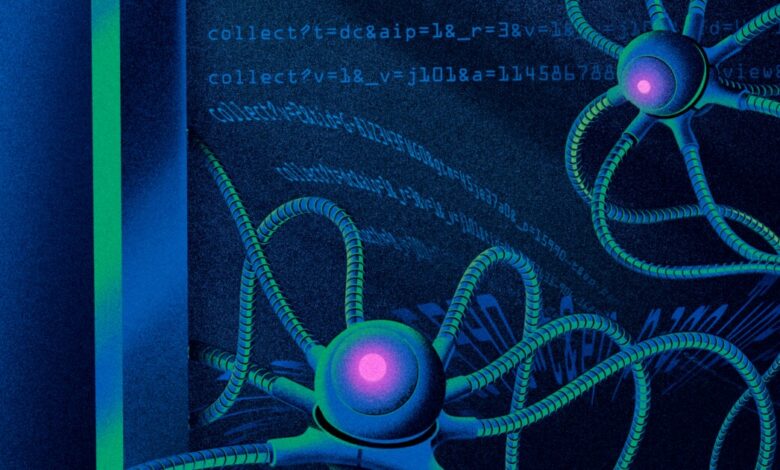

To look inside, The Chronicle gained access to two student accounts: one via Pearson MyLab, the other McGraw Hill Connect. The goal was to see what data was being shared with companies other than the publishers, and whether that reality aligned with what the publishers described in their privacy notices.

Using free Chrome developer tools in consultation with web-tracking experts, a Chronicle reporter analyzed changes to network activity as she navigated around the courseware products and performed actions a student might normally while taking a course. On one of the platforms, doing so appeared to confirm cases of data-sharing beyond what the publisher promised its users.

Every time the reporter logged in to Pearson MyLab and reached the course home page, web page details that included the user’s first and last name, along with the name of the college where the user was enrolled, were sent to Google Analytics. Whenever she viewed the account details page, Google Analytics got the user’s email address.

This contradicted Pearson’s privacy notice, which says that web-analytics services like Google Analytics only “collect and report information on an anonymous basis.” Pearson last year reported about 5.5 million units sold across three main courseware products, which includes MyLab.

The Chronicle also recorded other cases of data disclosure that could theoretically be used to help a company like Google build a unique user profile. For one, among the personally identifiable data sent to Google Analytics was a unique, eight-digit user ID that the reporter observed on a handful of different pages within MyLab. As the reporter interacted with the Pearson eBook, too, Google Analytics gleaned the name of the book and chapter she was reading — even the blocks of text she highlighted, and the exact time that she did so.

Presented with these finding, a Pearson spokesperson replied in a statement: “Pearson uses a variety of tools provided by third parties, with privacy protections in place, for the purposes of improving and personalizing the product experience for students. In customizing our users’ experiences within MyLab, we inadvertently captured certain personal information using Google Analytics tools, one of the third-party tools we use to help us build better user experiences. The information was collected for Pearson’s purposes only, and we prohibit Google from using this information for their own purposes. The information collected was first and last name, email address, and institution name. We have deleted this information, and it is no longer captured.”

A review of a Connect class yielded fewer questions. Visits to the homepage and the “Results” page, which tracks the student’s grades, disclosed to Google Analytics the name of the upper-level course linked to the account, the course semester, and the specific course section the student was in. The reporter also noted, as with Pearson MyLab, the presence of an eight-digit user ID that popped up on some pages, including the eBook.

McGraw Hill’s end-user privacy notice acknowledges that other third parties “collect information automatically from you” through their own tracking mechanisms. But there’s a stated purpose: “To enable the functions of the digital learning system, as well as customize, maintain, and improve our digital learning systems.” Asked how the information above met those standards, a spokesperson wrote in an email that the company uses Google Analytics as a “user behavior measurement system,” and that being able to differentiate between a course and section “provides us with the information required to make specific product decisions for improving student outcomes,” such as content or assessment updates.

The spokesperson added that the eight-digit user ID is “a custom generated value provided by McGraw Hill to Google Analytics” and “is not associated within any other data that would connect the information to other records.”

In both McGraw Hill Connect and Pearson MyLab, The Chronicle found no evidence of students’ grades, answers to assignments and assessments, or any unique written material, including messages sent to instructors, being shared with Google or any other third party. Still, privacy experts are wary. Priyanjana Bengani, a computational-journalism fellow at Columbia University’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism who reviewed the reporter’s analysis, said such findings underscore how murky the world of data privacy and web tracking is, and the need for both colleges and publishers to take it seriously.

“Even if it’s not intentional,” she said, “doesn’t mean it’s OK.”

“People are pretty flippant about privacy these days,” Bengani added. “I think it would behoove everyone to just be a little more careful about use of data.”

Some institutions require faculty members to follow a process when adopting courseware for a class.

Sheri Prupis, director of teaching and learning technologies in the Virginia Community Colleges system office, said there’s a systemwide “lock” in the learning-management system that prevents individual faculty members from integrating a new tool, including an unevaluated courseware product, without supervisor approval. In order for the lock to be lifted, and the tool integrated, the vendor must pass an industry-known risk assessment. The questionnaire asks, among other things, whether the vendor performs security assessments of the third-party companies that it shares data with, and for an explanation of why it shares institution data with each of those companies to begin with.

“As an administrator, it’s not up to me to say what [faculty] use — except when it comes to background safety,” Prupis said.

Meinke, at the University of Hawaii-Manoa, also pointed to his institution’s creation of an executive policy in 2021 that details data-protection requirements for third-party vendors — even those operating without a university contract. The policy explicitly notes its applicability “to any formal or informal agreements made by faculty that require students to purchase products directly from Third Party Vendors.”

While he hasn’t observed the institution being particularly aggressive around compliance, Meinke said there are resources online to help faculty members comply. There’s a Google form for instructors to submit tools to Information Technology Services for review, for example, and a spreadsheet that lists all of the third-party tools and platforms that ITS has reviewed previously.

Salo, at UW-Madison, doesn’t fault already-overburdened faculty members for not being data-privacy mavens. Still, she encourages them to learn — and employ — some best practices where they can: Having an ad blocker installed on their browser to get in the habit of thinking about, and checking for, tracking activity. Always at least skimming companies’ privacy notices, and asking clarifying questions. Finding, and leaning on, colleagues who specialize in data privacy and security.

“I would love to make myself obsolete as a higher-education data-privacy person,” Salo said. “I hate having to worry. But I do have to worry.”

Source link