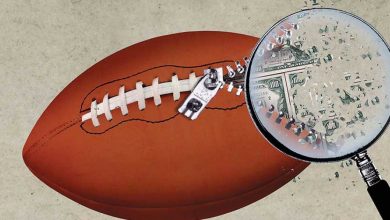

Bursting at the Seams and Battling in Court, Berkeley Faces an ‘Urgent and Real’ Student-Housing Crisis

[ad_1]

Cyn Gómez understands, from personal experience, how badly the University of California at Berkeley needs to expand its student housing. Desperate for an affordable place to live after returning from an academic program in Washington, D.C., he spent three weeks crashing on friends’ couches and struggling to keep up with his studies before reclaiming a coveted spot in a student co-op.

Still, when construction crews arrived this month at nearby People’s Park to begin clearing the area for a planned student apartment complex, the incoming third-year student was among the protesters linking arms and trying to keep them, and the dozens of police officers who accompanied them, away. Protesters broke through security fences and clashed with construction crews on August 3, forcing the university to retreat.

As Gómez sees it, the historic park is the wrong place for Berkeley to be breaking ground. The university acquired the lot in the late 1960s by eminent domain. In 1969, protesters seeking to reclaim it as a community park and a space for concerts clashed with police officers in riot gear. The confrontation left one person dead and many injured.

Since then, the park has become a symbol of community resistance and countercultural protests. In recent years, many of the people gathering there are financially struggling or homeless. The planned student-housing project has drawn fierce opposition despite the university’s commitment to helping resettle many of the people who have been living there.

“From a student-activist standpoint,” Gómez said, “it’s frustrating to see the struggles of Berkeley students pitted against the needs of unhoused people living in the Bay Area.”

The tensions playing out in People’s Park are an extreme example of the challenges facing colleges with housing shortages, as students eager to return to an on-campus experience run up against limited dorm space and sky-high rents for off-campus accommodations.

It’s frustrating to see the struggles of Berkeley students pitted against the needs of unhoused people living in the Bay Area.

Those tensions also reflect the competing demands facing the University of California and its flagship campus today. The housing stock of the UC system hasn’t kept up with the growth in the state’s population and the record-setting numbers of students applying for admission. Despite adding 15,000 student beds from 2016 to 2020, thousands of students across the system remain on wait lists for housing. Meanwhile, as students have spilled out into surrounding neighborhoods, putting pressure on traffic and housing prices, community groups have fought back, frequently in the courts.

Berkeley houses just over one in five of its undergraduate students, the lowest percentage in the UC system. Freshmen are guaranteed access to one of the campus’s 9,875 beds. The university wants to extend that to two years for undergrads, and at least one year for transfer and graduate students, a goal that would require 8,000 extra beds.

On-campus dorm rooms and apartments generally go for around $1,100 to $1,900 a month, depending on how many students they house, while one-bedroom apartments in Berkeley typically cost well over $2,000. To make ends meet, many students live far from campus or squeeze into single-family homes that have so many beds they’ve been dubbed mini-dorms.

“The student-housing crisis is urgent and real,” Berkeley’s chancellor, Carol T. Christ, wrote in an August 15 message to the campus explaining the need for the People’s Park complex. “Every year we are forced to turn away thousands of students seeking below-market-rate campus housing. It is a crisis that particularly impacts students from low-income families.”

A Systemwide Housing Crisis

The People’s Park project, which was halted by a court order following this month’s protests, is the most contentious of the six housing complexes the flagship campus is struggling to move ahead with. The $312-million project would house more than 1,100 students and 125 people who are currently homeless in two wings of a building — one rising 11 floors high and the other six. Combined, the six projects would supply 3,650 beds, or less than half of those needed.

Meanwhile, the university system continues to face pressure to expand. Last month the system announced plans to increase enrollment by 23,000 students over the next eight years — the equivalent of adding another campus to the 10-campus system. Gov. Gavin Newsom’s 2022-23 state budget provides enough money to do that. But if it can get more money from the state, the university would like to raise that to 33,000 additional undergraduate and graduate students by 2030.

Each campus will tailor growth plans to its own circumstances. Despite widespread criticism of its design, the University of California at Santa Barbara is moving ahead with Munger Hall, an enormous, 11-story residence hall that would house more than 4,500 students, mostly in small, windowless private bedrooms interspersed with common living spaces. It’s based on a design dictated by Charlie Munger, a 98-year-old billionaire and close associate of Warren Buffett. Construction could start early next year and be finished by 2026.

Berkeley, like Santa Barbara, has to abide by long-range development plans formed with input from their communities. Berkeley’s calls for its undergraduate population to grow by 1 percent or less over the next 15 years. Nevertheless, it’s expected to accommodate many of the increasing numbers of California residents in the system’s growth plan.

Here’s how those seemingly contradictory directives might play out: About a quarter of the growth at the Berkeley campus, as well as the Los Angeles and San Diego campuses, is expected to come from replacing out-of-state and foreign students with Californians. Berkeley, where about a quarter of students are from overseas or out of state, will also need a major infusion of state money to achieve the goals, set by some lawmakers, of having Californians represent closer to 90 percent of students. Those students pay less and need more financial aid, especially now that the test-optional university is attracting so many more first-generation and other disadvantaged students. The current California Legislature has committed to making up the difference for the loss in tuition money, but some worry that future legislatures might not.

Much of the rest of the growth would rely on limiting the numbers of students physically on campus at any given time. That will require a delicate dance, welcoming many more students, as long as they don’t linger. Urging them to stay home and study online. To enroll at Berkeley but spend time away. To spread themselves out by taking courses during the summer, ideally online.

One way to reduce the number of students on campus is to improve the four-year graduation rate (currently 81 percent for incoming freshmen) and two-year rate for transfer students (currently 60 percent). Tutoring can be expanded and data more closely analyzed to identify bottleneck courses and swoop in on students who are struggling.

The university also plans to expand enrollment in summer courses, many of which will be online. Bridge programs will provide mentoring and support to help students get on track and stay there.

The courts are open to anyone with means and motivation to challenge us in court, and there is no shortage of people who sue us at every turn.

Options for remote courses can be expanded, and faculty members given more help in designing and delivering such courses and programs. Berkeley was able to avoid large-scale admissions cuts this past spring by requiring some accepted students to start out online.

Berkeley also plans to widen participation in study abroad and remote internships, which would further reduce on-campus enrollments. Among the programs offering off-campus study are Cal in the Capitol, in Sacramento, and UCDC, in Washington, D.C.

Even with those steps, there’s no getting around the need to build in areas where opposition runs deep, said Dan Mogulof, a Berkeley spokesman. “We need to build on every piece of university-owned property in close proximity to the campus,” he said. “People’s Park is one of those sites.”

Competing Needs

To respond to concerns about the development, the university spent nearly $5 million to help move people who had been living in the park to transitional housing in a converted motel. It also spent $1 million in a joint effort with the City of Berkeley to open a daytime gathering space where people without housing can get food and services. Just over 60 percent of the park will be left as green space, and the university plans to work with local groups to commemorate the history of a park widely regarded as a hotbed of political and social activism.

The university’s overtures to the community did little to appease activists who converged on the site after midnight on August 3, when construction crews with chain saws began clearing trees from the park. After the clashes with protesters, who damaged some equipment, the university withdrew its crews, citing safety concerns.

Two days later, a state appellate court approved an order halting all construction until October. The university can maintain fences and security at the site, but it can’t proceed with construction or demolition. The delay was intended to give the judge time to consider an appeal by two community groups that have been fighting the project.

After agreeing to concessions from the university, the City of Berkeley has backed the campus’s plan for People’s Park, as have two-thirds of the students the university polled. Still, Mogulof said, “the courts are open to anyone with means and motivation to challenge us in court, and there is no shortage of people who sue us at every turn.”

If the court allows the university to resume construction in People’s Park, it plans to do so, as long as the work can be done safely, he said. Construction is expected to take three years.

Jonathan Lorenzo Dena is a formerly incarcerated, first-generation Berkeley student who spent time living on the streets to escape the crowded and chaotic living conditions at home. When he walks by the park and sees people living in makeshift tents, the problem of homelessness is staring him in the face, he said. “We forget that some of the students we go to class with don’t have housing.” The People’s Park development, while far from perfect, could help, he said. “Any housing that’s meant to be affordable, I’m for it.”

Dena, a transfer student from Cosumnes River College, in Sacramento, knows what it’s like to be so focused on basic needs that there’s little time or energy left to study. “It’s hard to do great in your courses when you’re constantly focusing on, ‘Where will I go after this semester ends?’” Dena said. Some leases, he said, are for one semester, and rent increases are common. “Some students who’ve been couch-surfing full-on withdraw because they just couldn’t figure it out. It was, ‘I was ready to go to school, but Berkeley wasn’t ready for me.’”

[ad_2]

Source link