Confirming Faculty Fears, Purdue’s Board Chair Says Trustees Chose President Like a Business

[ad_1]

When Purdue University’s trustees announced their new president this month, they left out some key information: how and why they had chosen that person.

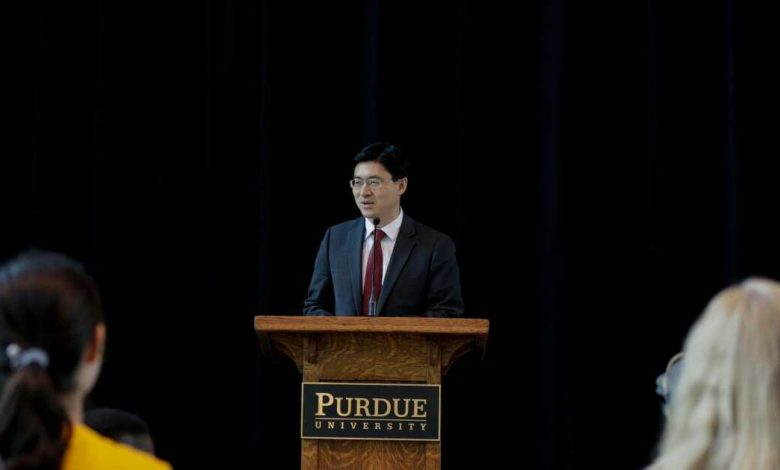

What made the event even more surprising was that the trustees announced the retirement as president of Mitchell E. Daniels Jr., who has led the university for a decade, at the same time they named his successor, Mung Chiang, Purdue’s dean of engineering and executive vice president for strategic initiatives.

Picking a college president is often described as the most important responsibility of a governing board, but that task is usually accompanied by at least a modicum of transparency and input from constituents, including faculty, staff, and students. The stealthy move to name a new president at Purdue has set off alarm bells nationally as the latest example of trustees’ willingness to ignore the core values of shared governance.

While it’s the Board of Trustees’ responsibility to hire the president, doing so without buy-in from campus constituents can lead to a backlash and a lack of trust in the new leader, said Leigh S. Raymond, a professor of political science and president of the American Association of University Professors’ chapter on the West Lafayette campus.

“There are different ways to run a university,” Raymond said, “and the board is choosing a way that is not productive and not good for the morale of faculty.”

While searches for college presidents have become more secretive in recent years, Purdue’s governing board may have set a new precedent for opacity. Not only was no search announced publicly, but the board did not even tell Chiang and other possible candidates that they were under consideration, said Michael R. Berghoff, the board chair.

Had we not been so certain about the candidate, we would have been more likely to have a search that looked outside.

Instead, the board evaluated several members of Daniels’s executive team “on the job” over a three- to five-year period, Berghoff said in an interview. Even as it approached a decision, the board did not conduct any formal interviews with Chiang, he said.

The board did not need to interview Chiang, Berghoff said, because Daniels had provided regular updates on the dean’s successes. In addition, Berghoff said, the trustees had already gotten feedback on Chiang’s performance from a variety of sources, including people on campus and elected officials who had worked with Chiang.

The process and decision resembled how the board of a large corporation might choose a new leader by considering talent that has been groomed from within, said Berghoff, who is the founder and president of the Lenex Steel Corporation.

“Had we not been so certain about the candidate,” Berghoff said, “we would have been more likely to have a search that looked outside.”

Corporate Decisions

Chiang, who earned a doctoral degree in electrical engineering at Stanford, has a lengthy list of accomplishments as an academic and entrepreneur, with numerous awards for research and teaching. He holds more than two dozen patents and has cofounded three start-ups as well as a global nonprofit group. His Purdue biography credits his leadership with improved rankings and enrollment at the engineering school as well as a significant rise in sponsored research.

But surprise announcements of campus leaders in other cases have sometimes ended badly both for the person who took the job and for the reputation of the institution. The challenge for those leaders, even when they are well qualified for the job, is that a flawed process, without public vetting, leaves them with a deficit of good will from the campus community, according to experts in governance.

“While the search process is intended to help gather diverse perspectives and ensure that the candidate is examined from all angles, it also serves to legitimize the process and build trust among stakeholders,” according to a written statement from Henry Stoever, president and chief executive of the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges, a nonprofit organization that promotes best practices.

Several presidents or system heads who were appointed as sole finalists and with minimal campus vetting have resigned under pressure, including F. King Alexander at Oregon State University and Mark R. Kennedy at the University of Colorado system.

Chiang is no stranger to Purdue, but faculty members are fuming over the board’s secrecy and are concerned the trustees considered only a narrow perspective in evaluating Chiang, even in his current position.

AAUP chapters on three of Purdue’s campuses, as well as the national organization, have issued statements condemning the board’s lack of transparency.

“There are lots of ways in which academic institutions are not the same as businesses,” said Alice Pawley, a professor in Purdue’s School of Engineering Education and past president of the AAUP chapter on the West Lafayette campus. In particular, she said, hiring at a university is meant to provide all job candidates with an equal chance to get the position based on their qualifications, not on favoritism.

It’s interesting that the board has adopted a corporate strategy. An academic strategy is meant to hire people on merit with as little bias as possible.

“It’s interesting that the board has adopted a corporate strategy,” she said. “An academic strategy is meant to hire people on merit with as little bias as possible.”

While Chiang’s academic credentials are appropriate for a leadership post, Pawley said, his administrative experience at Purdue is somewhat thin. Chiang was appointed dean of engineering in 2017 and has not yet gone through the typical five-year review for an administrator, she said.

Chiang also has not spent that entire time at Purdue, Pawley said, because he took a leave of absence to serve as an adviser to the U.S. secretary of state during the final year of the Trump administration. In the most recent year, Chiang has split his time between service as dean of engineering and as a vice president, she said.

Raymond, the AAUP-chapter president, said the board’s actions, in this case and others, are part of a larger trend toward the corporatization of higher education.

In recent years, Raymond said, faculty and other groups at Purdue have been shut out of decisions and actions that have a direct impact on academic issues, such as the creation of a new online institution from the purchase of the for-profit Kaplan University.

Last year the board approved a new civics-education requirement despite a vote against it by the University Senate and warnings from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, which advocates for academic freedom and free speech, that the process had undermined shared governance and faculty trust.

“It’s a culmination,” Raymond said, “of acting like an institution of higher education is effectively the same as ExxonMobil.”

[ad_2]

Source link