Court Orders Berkeley to Slash New Undergraduate Enrollment by a Third

[ad_1]

The University of California at Berkeley will have to slash new undergraduate enrollment by a third for the coming academic year, denying thousands of Californians a shot at attending one of the nation’s most sought-after colleges and costing it $57 million in lost tuition, unless the state’s highest court intervenes.

Responding to concerns about the effect of the university’s recent growth on surrounding neighborhoods, the California Court of Appeal last week upheld an Alameda County Superior Court order that Berkeley reduce enrollment for the 2022-23 academic year to the same level as in 2020-21. The university has asked the California Supreme Court to intervene, and hopes it will do so quickly, since the university says it is scheduled to send most of its acceptance letters by March 23. Most acceptance letters for graduate students have already gone out, the university said.

“If left intact, the court’s unprecedented decision would have a devastating impact on prospective students, university admissions, campus operations, and UC-Berkeley’s ability to serve California students by meeting the enrollment targets set by the State of California,” Berkeley said in a statement.

Public colleges throughout California are squeezed between competing demands from the state government, which ordered in recent years that they ramp up enrollment, and local community groups that object to the worsening traffic, rising housing prices, and environmental strain.

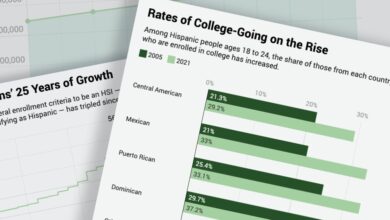

With climbing high-school graduation rates, especially among the state’s growing Hispanic population, more high-school students now qualify for admission to four-year universities. A record 250,000 people applied for freshman or transfer admission in the fall of 2021 to the university’s nine undergraduate campuses — up 16 percent from the previous year, a spokesman for the UC system said.

Not only is it harder to get into a state university, but there isn’t nearly enough housing as campuses struggle to expand their footprints, often in environmentally sensitive or densely populated areas.

“Berkeley acknowledges that it has a housing crisis, but it’s very hard to address it if we’re being sued every step of the way,” a campus spokesman, Dan Mogulof, said on Tuesday.

The enrollment-cap order is a result of a lawsuit filed against Berkeley, University of California regents, and other parties in 2019 by a group called Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods. The group argued that the university hadn’t adequately considered the effect of its growth on police, fire, and ambulance services, as well as trash and noise. It also argued that students spilling out into the surrounding neighborhoods would drive up housing prices and so make more local residents homeless.

The court-ordered enrollment reduction would cost the university at least $57 million in lost tuition, Berkeley’s statement said, “which would impact our ability to deliver instruction, provide financial aid for low- and middle-income students, adequately fund critical student services, and maintain our facilities.”

In a typical year, Berkeley sends letters of admission to about 21,000 freshman and transfer students, and ends up enrolling about 9,500 of them. Based on the usual yield rates, the university would have to cut at least 5,100 such offers to achieve the results ordered by the court. The number of new undergraduates enrolled — most of them state residents — would drop by about a third.

Requiring Berkeley to lower its enrollment to the 2020-21 level is particularly tough, the university argued, because in that year the Covid-19 pandemic prompted an unusually large number of new and continuing students to take time off. In addition to appealing the latest ruling, the university plans “all hands on deck” as it explores ways to mitigate the order’s effects, Mogulof said. It could give students incentives to graduate early, for instance, or determine which programs could offer more online classes.

In a statement posted on Monday on Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods’ Facebook page, Phil Bokovoy, its president, wrote that the university could easily comply with the court-ordered enrollment cap without hurting in-state students by limiting offers of admission to out-of-state, international, and certificate-program students. The group also made that argument, which the university has disputed, in court.

“UC-Berkeley students themselves have repeatedly said that UC should stop increasing enrollment until it can provide housing for its students,” he said. “Berkeley residents don’t want a repeat of the housing crisis in Santa Barbara during the current school year, where students were living in cars and the university had to put them up in hotels due to overenrollment.”

The housing squeeze has prompted some unconventional and controversial solutions in the state. The University of California at Santa Barbara has come under fire for its plan build a massive, 11-story residence hall that would house more than 4,500 students, 94 percent of whom would have small, windowless private bedrooms. It’s based on a design dictated by Charlie Munger, a 98-year-old billionaire who’s been described as Warren Buffett’s righthand man.

[ad_2]

Source link