Despite Sky-High Inflation, No Sign Yet of Surging Tuition Costs

[ad_1]

While high inflation continues to bedevil the wider economy, those price increases have yet to translate into significant spikes in college-tuition costs across the nation, according to data released on Tuesday by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Since August 2021, out-of-pocket college-tuition costs for households have climbed by 2.79 percent in a 12-month span, according to the bureau’s analysis. In contrast, prices across the economy grew by 8.3 percent in comparison with a year ago.

Muted tuition inflation, coupled with the increased costs of most goods and services, is likely to squeeze colleges financially, said Robert Kelchen, a professor of education at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Student-derived revenue typically accounts for about 75 percent and 50 percent of total operating revenue for private and public universities, respectively, according to Moody’s Investors Service, a credit-rating agency.

To be sure, some institutions are jacking up their sticker prices for the 2022-23 academic year to combat the effects of inflation. In Iowa, regents overseeing the state’s three public universities voted to raise tuition by 4.25 percent. Trustees at Pennsylvania State University took a similar approach, approving a 5-percent tuition-rate increase. “We are caught in an inflationary vise,” wrote President Robert A. Brown of Boston University in May, when he announced that tuition would go up by 4.25 percent for the coming academic year.

Apart from these and other examples, a broader appetite to raise tuition rates has yet to manifest itself. Indeed, the post-pandemic era of subdued tuition-price growth looks nothing like the market that colleges enjoyed in the 1980s, ‘90s, and 2000s — decades defined by soaring tuition prices, according to historical data.

Why aren’t tuition prices rising like they once did?

There are most likely several factors in play. In the past decade, some consumers have grown more price-sensitive regarding the cost of college. That interest in affordability, in turn, reduced the commercial advantage of institutions and spawned relatively modest tuition increases. Meanwhile, the population of graduating high schoolers has stagnated. With increased competition to recruit a freshman class, most institutions have lost additional leverage to set prices, though did still manage to eke out revenues in a low-inflation environment. Of course, that was until a historic pandemic led to additional enrollment losses, and price increases rippled across the economy.

“Most colleges just don’t have the market power to increase tuition anywhere near the rate of inflation,” said Kelchen.

Without surges in enrollment or significant revenues from nontuition sources (such as donors), Kelchen said, institutions will probably struggle to, for instance, finance competitive wages for employees, or subsidize programs outside of certain core services.

“This is a set of circumstances most people in higher ed have never seen before,” Kelchen said.

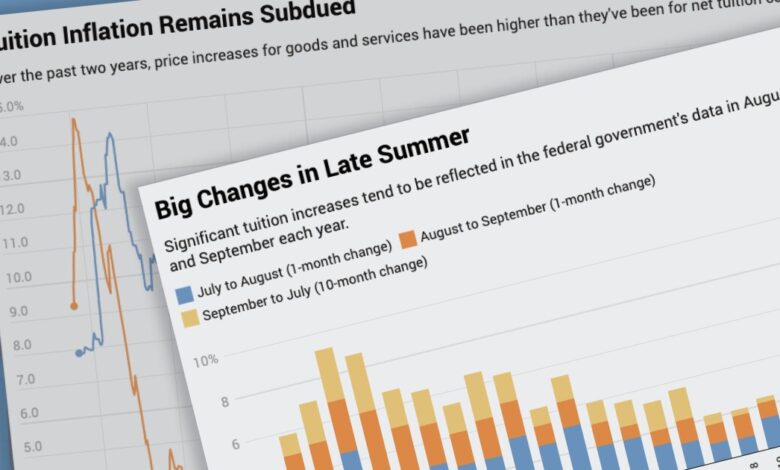

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ analysis indicates that college-tuition prices traditionally rise most significantly in August and September, relative to fainter increases calculated during the rest of the academic year. September index values will be published next month. So, while tuition doesn’t appear to have spiked during the past two months, that doesn’t eliminate the possibility of sectorwide tuition changes sometime in the future.

[ad_2]

Source link