Everybody Has a Secret

[ad_1]

A Brooklyn native, raised in a traditional Jewish household, he is amused by a satirization of the sexual fantasies of New Yorkers.

He is married with children. But he dreams at work about a sojourn in Paris with a woman other than his wife — someone who enjoys a good bistro; someone who makes his heart hurt.

He asks saucily if he might “lure” her with a knish.

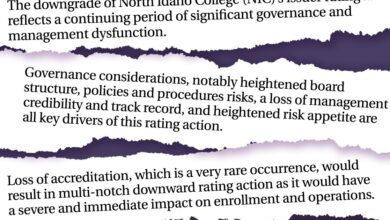

This is the portrait of Mark S. Schlissel that emerges from 118 pages of documents that the University of Michigan’s Board of Regents made public on a Saturday evening in January, shortly after they had removed him as president. In this collection of cringey communications between Schlissel and a subordinate, the university’s former top executive is stripped of his veneer of esteem, reduced instead to a lovestruck buffoon. All of it was so unbecoming of a man in Schlissel’s position, the regents agreed, that he should be summarily fired with cause.

Schlissel’s termination ranks among one of the more profoundly embarrassing firings of a major university leader in modern memory. Instantly memeable, excerpts from the emails quickly wound up on T-shirts and stickers. Before the Sunday sun had risen, some prankster had chalked the word “Lonely” on a campus sidewalk above a Michigan “M,” referencing one of the messages Schlissel had signed with the first letter of his name.

Turbulence around Schlissel was nothing new. He had, since 2020, worn the scarlet letter of a Faculty Senate vote of no-confidence, drawing the ire of professors for his handling of the pandemic, among other things. His tensions with the board, whose members are elected by statewide vote, had begun to bleed into public view. Even so, most expected this to end just as it often does for people in Schlissel’s rarified air: The president walks away with warm regards from the board and giant fistfuls of money. Schlissel’s transgressions upset this timeworn choreography.

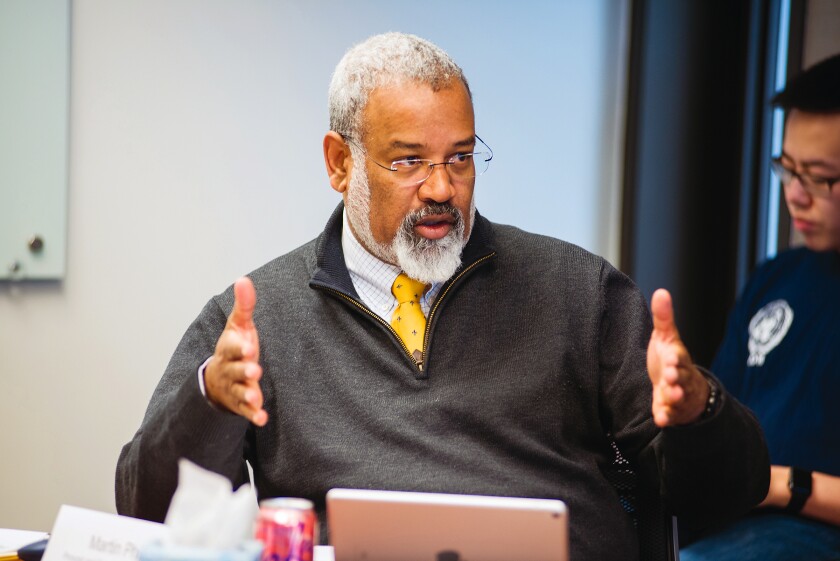

But his story is about more than a president getting crosswise with his board, or what appears to have been a workplace romance. The university’s recent history imbues his downfall with a complicated resonance that people in Ann Arbor are still sorting through. His firing came less than two years after Schlissel dismissed the university’s provost, Martin A. Philbert, who was accused of sexually harassing multiple women over the course of 15 years at Michigan.

Taken together, the two cases sent a message that the the university’s problems with sexual misconduct go all the way to the top. It isn’t that simple. There is nothing in the public evidence that would definitively establish that Schlissel engaged in sexual harassment. Even so, he gave fodder to a more systematic criticism that Michigan’s leaders still don’t get it. After all of the apologies, the legal settlements, the training sessions, the promises, and the shame, something has yet to sink in at the highest levels. Something is left to understand.

Since Philbert’s firing, in 2020, the university has signaled its willingness to turn over every rock, hiring an outside law firm to investigate how the system failed. As president, Schlissel was a visible champion of this work. But new reporting from The Chronicle suggests that the job remains unfinished. A retired professor, who has not previously discussed with the news media her role in the Philbert case, told The Chronicle that she was met with intimidation and indifference more than 15 years ago, when she first reported allegations against the future provost. Another faculty member, who has not spoken with news reporters about the case before, said she was twice told that decision makers at the university believed in Philbert’s capacity for “rehabilitation.”

The University of Michigan’s administration considers the matter of Martin A. Philbert settled. But Schlissel’s firing cracks open history, inviting still unanswered questions. When powerful people cross the lines of propriety, who renders the final verdict on what really happened? Whose memory counts? Who is burdened by history, and who is allowed to forget it?

Carlos Osorio, AP

“I think the letter kind of speaks for itself,” Acker says. ”It’s a judgment question at the end of the day. And I think it’s clear from the letter, what was lacking here was judgment.”

Strictly speaking, Schlissel was fired for violating a morals clause in his contract, which stipulated that he must at all times comport himself in a manner that promotes the “dignity, reputation, and academic excellence of the university.” Nevertheless, the board saw fit to invoke the past, calling Schlissel’s conduct “particularly egregious” in light of his commitment to stamp out sexual misconduct at the university. The letter lets the reader decide exactly what’s being charged here. Is the board calling Schlissel a hypocrite or accusing him of harassment?

“Mark Schlissel is not a monster,” Acker says. “He’s not an evil, evil guy. Mark Schlissel was guilty of extraordinarily poor judgment. But I put him and Martin Philbert in very different categories. Martin Philbert was engaged in sexual harassment. I can’t say the same about Mark Schlissel.”

Schlissel declined an interview request, and Philbert could not be reached for comment.

When the revelations about Philbert came to light, there was enormous pressure on Schlissel to make changes that would confront sexual misconduct directly. One of the Philbert-inspired policies, adopted last summer, proved prescient: A supervisor at the University of Michigan is forbidden from initiating an intimate relationship with a subordinate, and any such relationship must be disclosed. (The regents, to whom Schlissel reports, said they learned of his relationship with a subordinate through an anonymous complaint — not Schlissel.)

In firing Schlissel, however, the board was silent on the question of whether the president had violated the supervisor-supervisee relationship policy. Acker declined to state a position on the matter. The university adopted the policy, effective immediately, on July 15. Around that same time, Schlissel sent a few tortured emails to the subordinate, inviting speculation that the president knew he either had to end the relationship or report it. “I still wish I were strong enough to find a way,” he wrote on July 1.

There was an honorable option staring Schlissel in the face; he could have resigned before July 15. Instead, he hung on and secured a lucrative exit agreement. Schlissel, who is 64 years old, signed a contract in September that entitled him to receive his presidential salary of $927,000 for 2½ years after his planned resignation, in 2023. (Since he was fired for cause, Schlissel will not be paid the 2 ½ years of presidential salary, university officials confirmed. But he retains his rights as a tenured faculty member.)

Even after the regents changed the relationship policy, Schlissel continued his familiar emails with the subordinate. He told the woman she was sexy and suggested a “private briefing” with her. He forwarded her an ad for the Hulu series Only Murders in the Building, which carried the tagline “Every Body Has a Secret.”

“If we’re talking about a future president,” Acker says, “I would have a really hard time with the president of the University of Michigan having an extramarital affair with any staffer. The presidency is a different job than every other job on campus. You’re not a researcher, necessarily; you’re not a hospital administrator. You’re not just the face of the university. You’re everything. And so that requires a special degree of care that no other position requires.”

“You are the president 24 hours a day,” Acker continues. “No matter what you do, whether you’re sitting in Zingerman’s or presiding over a board meeting, you’re the president of the university. So that requires you to be ethical 24 hours a day and represent our values for 24 hours a day. So, yeah, I think that engaging in a relationship with a university staffer, extramaritally [sic], would not be wise of a future president. No.”

Schlissel’s case raises complex questions about the private lives of college leaders, including whether they can really have private lives at all. There are questions, too, about the power dynamic that exists between any college leader and a subordinate, and what effect a boss’s affair may have on the workplace. But there is a simpler reason people couldn’t stop talking about Schlissel’s demise: The president made a fool of himself; it’s an easy story that an undergrad could render in full with a piece of sidewalk chalk. Less simple, and more consequential, is how the university responded to some of the earliest known allegations of sexual harassment made against a future provost.

The generally accepted understanding of what went wrong in the case of Martin Philbert is contained in a law firm’s nearly 100-page investigative report, which the university released in 2020. But there is another history. It can be found in a black notebook that, for many years, gathered dust in a professor’s basement.

Loch-Caruso came to Michigan, in 1986, as an assistant professor on the tenure track. In 2001, she became the first woman ever to be named a full professor in the department of environmental health sciences, which, at that point, had existed under various names for more than 100 years. Philbert joined Loch-Caruso’s department in 1995. He was a promising scientist who, Loch-Caruso surmised, was being groomed by higher-ups for administrative roles.

Loch-Caruso and Philbert weren’t close. But she kept tabs on a graduate student who worked in his lab, because the student had been supported by a training grant that Loch-Caruso directed. In May 2005, Loch-Caruso bumped into the graduate student in a hallway of the public-health building. The conversation “started really going sideways,” Loch-Caruso said. The woman, Loch-Caruso said, told her Philbert was “a bad man. He did bad things.”

Loch-Caruso asked for specifics. Philbert had kissed her, the woman said. Where? Loch-Caruso asked. “By this point, she was crying,” the professor recalls. “And as she’s crying, she points to her neck. And I was just aghast, because there’s no way I believe that that woman was lying. That young woman was terrified, scared, and being bullied into having to accept inappropriate sexual behavior towards herself.”

The woman seemed afraid of retaliation from Philbert, who held sway over her future, Loch-Caruso said. The professor had her own fears, too. Philbert appeared ascendant at the university, and she could envision a day when he could harm her career. He might even become her dean.

The WilmerHale law firm, which the university hired in 2020 to investigate the Philbert case, identifies Loch-Caruso in its report only as “The SPH professor,” denoting her position in the School of Public Health. Before speaking with The Chronicle for this article, Loch-Caruso had never granted an interview with the news media or publicly discussed her role in the case beyond comments she made in a department faculty meeting after Philbert was fired. Now retired, Loch-Caruso says she finally feels free to speak about her experience without fear of retribution.

The professor’s notes, which are referenced numerous times in the WilmerHale report, appear to have been vital to the firm’s reconstruction of some key events. In interviews with The Chronicle, Loch-Caruso drew upon the notebook for reference. She also shared scans of relevant pages, redacting the names of Philbert’s accusers to protect their identities.

In June 2005, about a month after Loch-Caruso had spoken with the graduate student about Philbert, a research assistant who worked in Philbert’s lab asked to meet with Loch-Caruso, according to the professor’s notes. The researcher, who is identified in the WilmerHale report as “E-1,” told her that Philbert had asked her to marry him, spoke of having “caramel colored babies” with her, and referenced “chocolate syrup sex.” Loch-Caruso wrote the words down, she said, “because they were so specific and weird.”

The researcher did not want to be named as Philbert’s accuser, Loch-Caruso said, but “I think she hoped I could do something that would not involve her.”

Sarah Kunkel, The Michigan Daily

On August 8, 2005, Loch-Caruso reported the allegations to four different university officials. Among them was Kenneth E. Warner, who was then dean of public health. Drawing on her notes, Loch-Caruso’s rendering of the phone call she had with Warner differs greatly in tone and content from what wound up in the WilmerHale report. It’s an interaction that, more than 16 years later, sticks with Loch-Caruso as an example of institutional indifference toward protecting people from harassment. (Warner, who retired in 2017, is a distinguished university professor emeritus of public health; professor emeritus of health management & policy; and dean emeritus of public health.)

According to Loch-Caruso, Warner was displeased when she informed him that she had, earlier that day, reported Philbert by name to Lori Pierce, vice provost for academic and faculty affairs. (Pierce had told Loch-Caruso that, if she was reporting misconduct, she had to name the faculty member.) The dean told her, “You shouldn’t have done that,” according to her notes. Warner advised Loch-Caruso that she was potentially liable in some way, the professor said.

The meeting shifted to a discussion of what would now happen to the graduate student, who had begged Loch-Caruso not to report Philbert. According to the professor’s notes of the meeting, the dean told her that the student could not be protected from retaliation. “I told Ken that the student was very afraid,” the notes state, “that the faculty member would know she had reported his behavior + that she would suffer retribution. Ken said he could not protect the student from retribution. He agreed it was likely that the faculty member would suspect the student + retaliate, even if by subtle means such as not being available to the student at critical times. I said that this was a poor statement of the system if it could not protect the student. He said yes it was, but that’s the way it is.

“Ken’s last words to me were, ‘You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t.” (The exchange about retribution, and this quote in particular, does not appear in the WilmerHale report.)

In his interview with investigators, Warner said he did not remember the conversation. According to the report, Warner said he would “never have suggested” that the professor not report the information. “On the contrary, he would have encouraged her to do so,” the report states. “He told us that he was concerned only about public accusations in the absence of evidence, and that it was plausible that he suggested that the SPH Professor be careful if that were the situation.”

After her meeting with Warner, Loch-Caruso wrote in her journal that “Ken Warner never expressed concern for the women complainants. Rather, the majority of conversation focused on the rights of the faculty member against whom these complaints were made.” Reflecting on the passage, Loch-Caruso said, “That bothered me a lot. I was worried about the women. He was worried about Philbert, in terms of protection.”

The Chronicle contacted Warner by email and phone to discuss the Philbert case and Schlissel’s firing, but he declined an interview. In response to a detailed summary of Loch-Caruso’s recollections, Warner provided a statement via email. “This was an enormously challenging situation,” Warner wrote. “I felt a great deal of sympathy for the women involved in Dr. Philbert’s atrocious behavior. I was troubled, and seriously constrained, by the limits of what university officials said we could do or say in the absence of the filing of formal complaints.”

The university never opened a formal investigation into Philbert, citing a lack of cooperation from the women. But Warner told investigators that he had found the allegations credible and had “read [Philbert] the riot act,” putting “the fear of God in him.” Philbert continued to harass the researcher, who quit her job in the lab, according to the report. The doctoral student never completed her Ph.D., Loch-Caruso said.

David Ramos, AP, Shutterstock

According to the WilmerHale report, Pierce had been directed by Philip J. Hanlon, who was provost at the time, to ask female faculty members and graduate students in public health if they had concerns about Philbert. Hanlon, who is now president of Dartmouth College, had by this point been apprised of the 2005 allegations.

Loch-Caruso met with Pierce on November 8, 2010. At first, Pierce said that the two had never met, the professor said. Loch-Caruso was “flabbergasted” by the assertion, she said, given the gravity of their interactions five years before. “It got hostile quickly,” Loch-Caruso said. Pierce eventually admitted she remembered their prior meeting, the professor said, and then pressed Loch-Caruso on whether she had any new information: Did Loch-Caruso know if Philbert had engaged in any sexual misconduct since 2005? Had Philbert done anything sexually inappropriate to Loch-Caruso directly? Had Loch-Caruso ever witnessed Philbert doing anything sexually inappropriate to someone else? To all of these questions, Loch-Caruso said, she answered no.

“She sat across from me at the table, and she stared me in the eyes,” Loch-Caruso said. “And she had very bright red painted fingernails. And I just remember — it’s a very enduring memory, because she looked at me and she said there was ‘Not one shred of evidence’ for those women’s allegations. And she repeated it; she said it twice. And she tapped her nail on the table and stared at me.”

Loch-Caruso’s notes of the meeting are dated December 2, 2010, about three weeks after it took place. Many, but not all, of the details she provided in interviews with The Chronicle about this exchange are documented in the notes. The notes mention, for example, that Pierce had “tapped her fingernail on the table.” Pierce, according to the notes, stated “emphatically” that it was “highly unusual” nothing had come of the inquiries that had been conducted, in 2005, by the university’s Office for Institutional Equity, which was responsible at the time for investigating sexual-harassment complaints against faculty members. The words “Not one shred of evidence” do not appear in Loch-Caruso’s notes. “I didn’t write it down, but I do remember,” Loch-Caruso said. “She said, ‘Not one shred of evidence.’ And she said it twice, and she was staring me down while she said it each time.”)

Pierce, who is still vice provost, did not respond to emails requesting an interview. Kim Broekhuizen, a university spokeswoman, told The Chronicle via email that Pierce had not received the interview requests, which were sent to an address listed in the university’s directory.

“The notes you provided from the meeting with her are not consistent with her recollections,” Broekhuizen wrote, “and are not what is detailed in the WilmerHale report. “And given her work in cancer care, Dr. Pierce does not wear nail polish.” (Pierce is a radiation oncologist.)

To Loch-Caruso, the implication from the meeting with Pierce was clear. She wrote in her notes, “I felt like she was implying that the students who came to me about Martin 5 years ago were lying, + that perhaps even I was lying. I felt hung out dry.” Loch-Caruso feared that, if Philbert became dean, she could be vulnerable to retaliation. “I was angry,” Loch-Caruso wrote in her notes. “I spent minutes staring at Dr. Pierce. I asked her how I would be protected if Martin became dean. She said the provost [sic] office could do nothing for me.”

Loch-Caruso said she “felt intimidated into silence.” Leaving the meeting, the professor said, she gave a “parting shot,” telling Pierce, “You are letting down the women of the university.”

“I literally walked out,” Loch-Caruso said, “and thought, ‘What did I expect? Truth? Justice? What a fool.’ I went into that meeting thinking that maybe something would happen. And I walked out defeated and intimidated.”

As with Loch-Caruso’s meeting with Warner, the WilmerHale report describes the professor’s interaction with Pierce as far more benign than Loch-Caruso recalls it. The report notes flatly, “The SPH Professor said she was unsettled by the meeting.”

Reporting back to Hanlon, Pierce told the provost that she “had found nothing negative,” the WilmerHale report states, “and that the SPH Professor’s account of Philbert’s conduct in 2005 was ‘strikingly different’ from what she was told by everyone else with whom she spoke.”

Loch-Caruso’s telling puts a substantially different spin on what, in the context of the WilmerHale report, is cast as Pierce’s ill-fated fact-finding mission. As Loch-Caruso interpreted it, what Pierce had billed as a garden-variety reference check was instead an unambiguous dressing-down, putting Loch-Caruso on notice that she needed to back off. It is among several instances in which the report, which has served as the definitive history of these events, omits something critical about Loch-Caruso’s perspective: There wasn’t just an insufficient investigation; there was intimidation.

“Take the WilmerHale report for what it is,” Loch-Caruso said. “It was not a deposition. There was no oath of truth. Too often WilmerHale has been held up around the university as being the end, but it really should have been the beginning of an investigation at the university.”

In response to The Chronicle’s reporting, Broekhuizen, the university spokeswoman, emphasized the breadth and independence of the WilmerHale investigation. “WilmerHale had unfettered access to do its work, interviewing more than 200 individuals and reviewing 2 million documents from the Bentley Historical Library, 125 boxes of paper personnel files and tens of thousands of other documents,” Broekhuizen wrote in a statement. “The nearly 100-page investigative report WilmerHale issued was made available to the public at the same time the university was provided access. The university fully cooperated with the investigation.

“We have enacted systemic changes that are transforming how the university prevents and addresses sexual and gender-based misconduct.”

In 2017, a little over six years after her meeting with Loch-Caruso, Pierce served on the search committee that led to Philbert’s appointment as provost — making him the university’s second-highest-ranking administrator. During his time as provost, Philbert was “in simultaneous sexual relationships with at least two university employees, sometimes more,” the WilmerHale report states. “He pressed some of these women to send him explicit photos, which he stored on his university-owned devices. And he engaged in sexual contact with them in university offices, including with one woman on a near-daily basis for a time. These relationships took a toll on the environment in the provost’s office and created uncomfortable dynamics among some staff.”

As a member of the provost-search committee, Pierce told investigators, she did not share what she knew about Philbert with other members or Schlissel, who chaired the group. She “did not think about it,” Pierce said. There had been “no evidence to support” the allegations,” she said, “so it was just gone from [her] mind.”

Elaine Cromie for The Chronicle

“She was very distressed,” Stewart recalled in a recent interview. “She felt helpless to protect these younger people.”

In her role, Stewart often heard from women who were being harassed or knew of harassment toward others and were unsure of what to do. She leveled with Loch-Caruso as she would have with anyone else: “When people won’t come forward, there’s not much anyone can do. But you can at least inform people that this has happened, so there’s some potential for institutional memory.”

Institutional memory. Sometimes that’s all there is. In Stewart’s experience, harassment allegations seldom stick without the cooperation of accusers or “smoking gun” evidence — “often email, ironically,” she says. Absent that, Philbert was unlikely to be disciplined or fired. But promotions to dean, and later to provost, were a different matter. By reporting what she knew, Loch-Caruso had flagged Philbert as a risk; in Stewart’s view, that should have been sufficient to block his advancement.

“Nobody’s got a God-given right to these positions,” Stewart said. “It is always a calculus about, What are the gains and what are the risks of appointing anybody to these positions?”

Stewart took steps, which have not been previously reported, to alert decision makers about the risks of promoting Philbert. Before he was promoted, to dean in 2010 and to UM’s top academic job in 2017, Stewart contacted the provost’s office with a warning, she said. “I said both times, you should know there’s this history,” she said. “In both cases,” Stewart said, “they said in response that they believed in rehabilitation.”

Stewart would not identify the person with whom she spoke in the provost’s office. Whoever it was, Stewart said, had done his or her job by elevating Stewart’s concerns within the provost’s office. It was never entirely clear to Stewart who on high had mentioned the power of “rehabilitation.” But the word stuck with her. It suggested to Stewart that upper administrators believed that the charges against Philbert were credible or at least that “there was a there there.”

“I remember thinking, and I think I said, ‘I believe in rehabilitation, but I don’t think you get promoted to a position of more authority over more people if there is a serious question about your judgment,’” Stewart said. “So that’s what I thought. Nobody cared what I thought.”

WilmerHale investigators never spoke with Stewart, she said, and her contacts with the provost’s office are not mentioned in the report.

Stewart joined Michigan’s faculty in 1987. She has read plenty of news articles about sexual harassment, and she tends to be disappointed in how the issue is covered. There is often a binary conclusion about where the fault rightly belongs, she said, “as though there are no structural problems to making this right — as if it’s a matter of lack of courage on the part of the victim, lack of courage on the part of administrators. ‘It’s all very straightforward: People should just step up and take care of business here.’ It’s not that simple. It’s much more complicated than that.”

Good policy can only go so far, Stewart said. Taking a zero-tolerance position on retaliation, as Michigan has done, may be important. But academic hierarchies and scholarly networks give predators a structural advantage. “It’s completely possible for me to kill your career because my network trusts me, so I can keep you from ever getting a job anywhere in your field,” Stewart said. “And what can the University of Michigan do about that? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. We pick up the phone and call each other. We see each other at conferences. Our network doesn’t operate through official channels that the university can control.”

Sexual-harassment allegations are not evaluated in a vacuum, Stewart said. Administrators, she said, fear they may be unable to protect complainants. They may fear the accused professors, too. “They are afraid of blowback from the individuals. They’re afraid of the blowback in the network. They’re afraid of losing that person from their firmament of fancy professors. They’re afraid of a lot of things. Can they make it stick? And do they think this person is going to fight back? That’s always a calculus.”

When Philbert came up for promotions, Stewart made her own calculation. “Do I think the risk was worth taking? No, I don’t. But why don’t I? Because I believed Rita. I believed the junior people who came to Rita.”

Joshua Lott, Getty Images

A new institutional memory had been created. But so much time had passed by this point. Bits of the Philbert story had died a little bit every day. People had forgotten things, or at least they would say they had forgotten things. Emails and notes were roadmaps that took the story only so far. Piecing it together was no small task. It would require the services of WilmerHale, an international law firm famous as a waypoint for high-ranking government officials, to sift through it all.

But even now, the picture that formed from the investigation is changing — shaded by events that continue to unfold at the university. Schlissel’s response to the crisis looks different when juxtaposed against his own indiscretions. He used the Philbert case as a catalyst for adding new positions to respond to sexual misconduct, and creating a standalone policy to prohbit retalation against complainants. To hear it from people who worked with Schlissel during this period, he seemed sincere in his belief that the university needed to do better. We know now that, at this same time, he was sending racy emails to a subordinate. There is another layer to the story.

Mysteries persist about what Schlissel may have known. He was provided with the results of a survey, in 2019, that contained anonymous feedback on Philbert, describing the provost as “a notorious sexual predator.” Schlissel said he didn’t remember seeing it. If he had, he told investigators, he would have reported it to the university’s Office for Institutional Equity.

“As a president, you would have immense numbers of documents to read, and you can’t read everything,” said Stefan Szymanski, a professor of sport management at Michigan. “But seriously, when there’s something like that” survey feedback, “I just find it incredible to think that he could not have read it — incredible to the point of barely being able to believe it.”

These sorts of doubts are pervasive at a university that, in trying to move on, finds in every twist of the Philbert story a reason for lingering skepticism. By selecting Mary Sue Coleman as interim president, the regents sought to signal stability. There is, to be sure, symbolic power in the decision. Coleman, who led the university from 2002 to 2014, is the only woman ever to have held the presidency. Who better to clean up the mess the men have made? But history clings to Coleman, too.

Records obtained by WilmerHale show that Coleman was alerted, in 2010, to the allegations that had been made against Philbert in 2005. Hanlon, who was provost at the time, told Coleman in an email of allegations that Philbert had “hugged and kissed and suggested sex with three female graduate students in his lab.” But, as Hanlon described it, there was “no evidence apart from rumor.” The matter “was resolved with the Dean having a frank discussion with Martin,” Hanlon wrote to Coleman.

In effect, a new institutional memory was created. There was really nothing here. Loch-Caruso, a full professor who had reported firsthand accounts of harassment from two different individuals, had been reduced to someone peddling “rumor.”

Speaking with investigators, Coleman said, “she did not remember receiving this email” from Hanlon, “nor did she recall learning about any allegations about Philbert as part of the Dean’s search (or at any other time),” the WilmerHale report states. But the investigation has informed the way Coleman sees the case now, she told The Chronicle in a recent interview at her office.

“It’s really interesting,” she said. “I’ve reflected on that a lot because Philbert, when he was promoted to dean, Phil Hanlon and I were talking about this. Phil was the provost, and we were talking about it. And Phil had gotten an anonymous email about some allegations about Martin. And we turned it over to the Office for Institutional Equity at that point.”

(According to the WilmerHale report, Hanlon discussed the Philbert allegations with the director of the Office for Institutional Equity. But Hanlon did not turn to the office’s “trained investigators” to conduct a follow-up inquiry, which he should have done if he had misgivings, the report states.)

In her conversation with The Chronicle, which lasted about 20 minutes, Coleman spoke without the benefit of notes about events that had transpired more than a decade before. But she conveyed a command of history that does not come through in the WilmerHale report.

“They investigated and they couldn’t get people to confirm anything or talk to them,” Coleman said. “It was anonymous. And you know, we felt like we just didn’t have the kind of evidence that we might need to interrupt somebody’s — and I don’t want to say interrupt somebody’s career, because, you know, if Martin hadn’t become dean here, he might have gone to another place.”

(At that very moment, a staffer knocked on Coleman’s door, saying she had another meeting. But she took a few more questions.)

Speaking with Coleman, it was difficult to reconcile what seemed today to be her clear memory of events with the hazy recollections she had previously shared with investigators. But Coleman’s view of history, specifically whether she had knowledge of the allegations against Philbert before he was promoted to dean, is shaped by what investigators showed her, she said.

“At the time I did not remember it,” Coleman said. “I did not remember it. However, they showed me the email that Phil sent to me. So, of course, I said, ‘OK, you told me about it.’”

“He showed me the data,” added Coleman, who is a trained biochemist.

As interim president, Coleman said, “One of my jobs is to regain trust and to accept as an institution we failed. There were things that were wrong, and that people weren’t aware of, or didn’t ask enough questions. Things happened and we accept that responsibility, and we know we have work to do.”

In 2020 the university announced that it had reached a $9.25-million settlement with eight women who said Philbert had subjected them to emotional and sexual abuse. This past January, days after Schlissel was fired, the university announced that it had reached a $490-million settlement with about 1,050 people who said they were abused by Robert E. Anderson, a physician who worked with the university from the mid-1960s to the early 2000s. (Anderson died in 2008.) The case inspired a prolonged protest by Jon Vaughn, a former Wolverines running back and abuse survivor, who maintained an encampment in front of the university president’s house for more than 100 days — and, more recently, chained himself to a tree there.

In recent years, the University of Michigan has made numerous organizational and policy changes aimed at preventing and responding to sexual harassment and sexual assault. In 2021 the university created the Equity, Civil Rights and Title IX Office or ECRT, a multidisciplinary unit that reports to the president and places greater emphasis on support and prevention, university officials say. (The unit replaced the Office for Institutional Equity, which, during Philbert’s tenure, had reported to him as provost.)

Under the terms of a settlement of a class-action lawsuit related to the Anderson case, Michigan plans to create a new group called the Coordinated Community Response Team. The team, of about 30 people from Michigan’s three campuses, is expected to provide input and advice on the university’s efforts related to sexual and gender-based misconduct. Michigan is engaged, too, in what the university describes as a “culture change journey,” a broad-based effort to identify the university’s common values and to acknowledge where it is falling short of its stated ideals. “Those things that happened,” Coleman said, “we didn’t live up to our values as Michigan. We know the work has to be done. We want to have a culture where it’s just inconceivable that this kind of misconduct could happen or that it would be much less prevalent.”

These dogs, Loch-Caruso complains aloud. “I’m never coming here again!”

Loch-Caruso, today a professor emerita, wears a soft green sweater with a white turtleneck poking out. When she laughs, her smile grows wide and toothy. On a dime, though, she turns deadly serious, her eyes widening in consternation, as she describes a system that failed so many women. There are real heroes in this story, she says, and they are the women who, anonymously or not, tried to stop Martin Philbert. But so many others showed so little courage, Loch-Caruso says.

For the university, the Philbert case is over. There has been a thorough investigation. Restitution has been paid. The institution moves on — informed by the past but not encumbered by it. Schlissel’s firing, embarrassing as it is, just proves a zero-tolerance maxim. But it isn’t over for Loch-Caruso. She still has a Google alert set for Philbert’s name, pinging her anytime he enters the news. All these years on, he lingers still. Something has changed, though. There were times when Loch-Caruso was so cynical she would not have discussed the case at all. Now she feels compelled to do so.

As day turns to night, and the fire pits on the gravelly terrace of Homes Brewery provide the last remaining light, Loch-Caruso is greeted by a younger colleague from the School of Public Health. The woman is on the tenure track at Michigan, just as Loch-Caruso was in the 1980s. They talk for a bit and laugh together. Loch-Caruso smiles as the woman leaves, walking off into the shadows ahead.

[ad_2]

Source link