Fielding Questions About Abortion, Colleges Turn to a Familiar Vehicle: the Working Group

[ad_1]

Following the Supreme Court’s reversal of a nationwide right to abortion, colleges in states where the procedure is restricted or politically tenuous are facing thorny questions:

What will happen to students who become pregnant and want to get an abortion?

Can staff and faculty members legally help them get one?

Can college funds be used to transport students and employees to states with less-restrictive laws?

What can be taught about abortion?

How will colleges prevent students who become pregnant from dropping out?

Will campus employees’ jobs be protected if they voice abortion-rights views or seek out an abortion?

Colleges are being careful about how they answer those questions. For the most part, their health centers have been tight-lipped about how they plan to support students’ reproductive health in states where abortion is mostly banned. Some employees and students are not satisfied with the answers, or lack thereof.

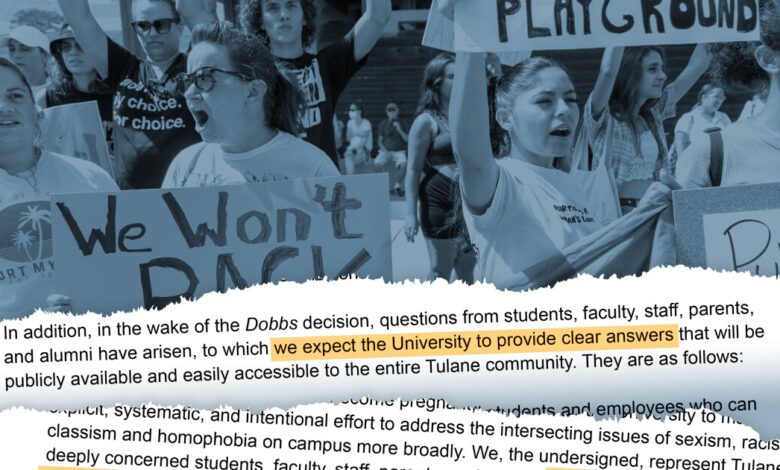

At Tulane University, in New Orleans, nearly 1,500 faculty members, staff, students, alumni, and parents signed a letter to the administration in July asking some of those questions and for the university to take a more clear and public stance that abortion should be a fundamental right. Abortion is now banned in Louisiana, except in some severe cases, such as to prevent the death of a patient. The letter’s signers asked the university to communicate that “abortion is a crucial component of reproductive health care” and that Tulane “supports reproductive autonomy.”

“As a leader in public health and medicine,” they wrote, “it is crucial that Tulane shows its commitment to supporting abortion rights and makes a definitive public statement about what the research shows.” The letter cited Tulane’s status as an R1 university and member of the Association of American Universities.

About 200 Tulane faculty members signed another letter back in May, before the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade. The letter asked the administration to communicate what students, faculty members, and staff could and could not do with regard to abortion in Louisiana.

“This is a huge public-health issue,” said Stephanie Porras, an art-history professor and one of the letter’s signers. She worries that students will seek her guidance in finding a way to get an abortion, but she will not know exactly who can help them.

The university should communicate to students, she said, what the law is, especially since many come from states with few restrictions on abortion. Tulane has made two nearly identical statements, one from human resources and the other from the dean of students, saying that the university recognized that “abortion is one of the most divisive issues of our time, and members of the Tulane community have passionate, deeply held opinions and convictions.” The statements encouraged students and staff members who needed help to reach out to campus health, student affairs, or the counseling center, in the case of students, or the university’s employee-assistance program, in the case of employees.

The statements also said that Tulane had convened two working groups made up of representatives from campus health, human resources, government affairs, and other departments.

“These working groups,” the statements said, “have been endeavoring to understand the ruling’s impacts and what changes we will need to make in response.”

‘Planning for 2 Extremes’

Several other universities have established working groups to try to answer some of the many questions about the implications of the court’s decision. Case Western Reserve University announced the formation of a reproductive-health working group in August, and Vanderbilt University created a task force in June.

At Michigan Medicine, the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor’s medical center and school, Dee E. Fenner knew back in December that such a group was necessary to sort through some of the many questions campus leaders at both the university and the hospital would need to be able to answer. Fenner, the chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, and Lisa Harris, the associate chair and a professor of reproductive health, knew that the State of Michigan had a 1931 law on its books that would make abortion illegal except to save the life of a pregnant patient.

“We’ve been planning for two extremes,” Fenner said. If Roe was overturned, either the law would go into effect or it wouldn’t, and Michigan could suddenly see a sharp influx of patients from nearby states with bans. “Right now it’s still a surge, so we’re seeing patients from all around the country.”

At the University of Michigan, a task force was created, along with several working groups, to consider what the overturning of Roe would mean for both the campus and the hospital. The campus group has been trying to mitigate the impact of the loss of abortion and reproductive-health care for students and faculty members, and to understand the ruling’s potential impact on health-insurance benefits, recruitment, retention, and development, Fenner said. A group focused on clinical care has been looking into the effect on patients and doctors during either scenario — a surge or a ban. Other groups have been considering the legal implications, the university’s messaging to students, employees, and the community, and the research that should be done to monitor how the shifting laws affect access to medical care.

“School just started at the university this week,” Fenner said. “We’ve been having forums, talking to students, talking to faculty. What do you need to know? What are you curious about? How is this issue impacting you?”

For now, the 1931 law is not in effect, but that could change. On Wednesday, Michigan Republicans blocked an effort to put a referendum on the November ballot that, if approved, would add the right to an abortion to the state’s Constitution. Whether the initiative appears on the ballot will probably be decided in court, The Detroit News reported.

Fenner said that clinicians at Michigan Medicine need to be able to adapt at a moment’s notice. If the 1931 law takes effect, they’ll need to make quick decisions about whether they can perform abortions if a pregnant women comes into the emergency room while hemorrhaging, for example, of if she needs radiation to treat cancer. At least until the November election, the task forces will continue to meet.

[ad_2]

Source link