Hay House: How Designer Sheila Bridges Made Space for Herself

[ad_1]

For more than two decades, the interior designer Sheila Bridges, a creative beacon for Bill Clinton, Tom Clancy and Sean (Diddy) Combs, the hip-hop mogul currently known as Love, has divided her time between Harlem and the Hudson Valley. Most of those years, Ms. Bridges, 57, retreated to an antique farmhouse in the town of Germantown in Columbia County, where she kept horses, sheep, goats and chickens. But in 2019, she moved into a 1,600-square-foot village house near Hudson, N.Y., that was built for her from scratch. (Since 2015, she has also maintained a small residence in Reykjavik, Iceland.) Speaking from her weekend property, she talked about designing to please the ultimate client: herself. (This interview was edited for length and clarity.)

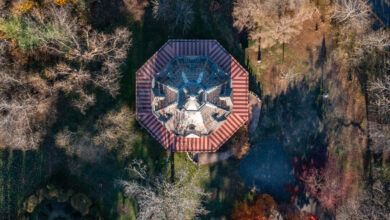

Why did you name your new Hudson Valley home Hay House?

It was sort of a joke. So many people have these very fanciful names for their houses. This is the opposite of a farm, but I have hay bales, which I brought here. And the house looks like a barn.

Was it a struggle to limit the size to 1,600 square feet?

It was a challenge, but the goal was to downsize my life on some level. I’m one person. The bigger the property, the more headaches in terms of upkeep. I’m trying to move away from that as I get a little older.

Did you at least leave room for a work space?

I didn’t design the house thinking that I would be here 24/7, but thankfully the attic is an open space. During the pandemic I turned it into a working studio. I had California Closets come in and build storage for our wallpaper, fabrics and umbrellas, and I put in desks. It worked out very well. It doesn’t intrude on the rest of my living space. One of the challenges we all have faced is how do you separate these spaces when you’re sitting at a laptop 12 hours a day.

I couldn’t help noticing that the wall treatments on the ground floor are, for you, quite plain.

With the architecture and design, it made sense to have white walls. I assume you noticed how much art I have on the walls; all the color and texture come from the art, the sculpture, the carpets, the upholstery. The bedrooms are very colorful. So basically, when you come into my house, it kind of looks like a white box, but as soon as you open any door, you’re hit with color and pattern in a way that I think most people associate with my work.

Which came first: the soaring ceiling or the decision to make mobiles a focal point?

Both.

Sorry, it can’t be both.

I always had mobiles in my rooms, even as a child. I knew that I wanted to have mobiles in this home and having 17-foot-or-whatever ceilings gave me the opportunity to do that. This is the first house that I’ve designed for myself that was built from the ground up. I wanted to surround myself with the things that I love and are meaningful to me. This is a home for a lot of art pieces that I’ve collected or that were passed down from my parents and that I’ve acquired over the years.

Many people struggle with what to do with inherited objects. Do you have advice about how to incorporate family treasures into one’s home?

I think whether inherited or not, if it’s something that you love you have to make room for it. I’m sitting here looking at a lamp in my living room that used to be in the living room of my parents’ home in Philadelphia for 50-some years and it just works. That’s the beauty of mixing periods. I love mixing old and new, vintage and modern, and it makes it easier to embrace the things that may have belonged to your family if you’re not so rigid about only having one style of furnishings in your home.

Your living-room beams and upper-floor ceiling remind me that you are not a person who is afraid to paint wood.

It all depends on the architecture and what you want the space to look like. In my apartment in the city, the wood paneling is painted in a Farrow & Ball Oval Room Blue, but it works because of the very classical sort of architecture. The paneling is mahogany, but it wasn’t in good condition. I didn’t have the money to restore it, so I decided to paint it, which really helped to hide a lot of those flaws. This space is brand new, so the white paint seems to work very well. There’s not a specific rule.

Seven years ago, you designed a sequel to your Harlem Toile de Jouy wallpaper called Hudson Valley Toile that gently poked fun at city people pouring into the region. You showed a gay farmer couple in the style of “American Gothic,” a station wagon driver searching for foie gras, and Rip Van Winkle waking up on a crowded Rip Van Winkle Bridge, which spans the river between Hudson and Catskill. Ignoring for a moment that this work is in the Brooklyn Museum’s permanent collection, would you design the same motifs today?

These scenes are like visual tropes. They became a little clichéd. We’ve seen them all play out. Toile is a fun way to document them. I should add that the roofed structure on the bridge behind Rip Van Winkle was recently torn down. Someone commented recently that one of the great parts of documenting these things in wallpaper is preserving what no longer exists.

Though you no longer own a farm, you still have almost an acre to tend. What are you doing out there?

My property gets a lot of water, so there’s a rain garden. I also have raised beds and last year I grew tomatoes and kale and lettuces and spinach and cucumbers and all kinds of herbs. Nothing super complicated. It’s fenced because I’ve always had dogs and I want to keep the deer out. I just looked out my window this morning and saw a doe munching on my neighbors’ hedges across the street. My neighbors spend the winter in Florida and I’m sure they’ll come home to some newly shaped shrubs and trees.

For weekly email updates on residential real estate news, sign up here. Follow us on Twitter: @nytrealestate.

[ad_2]

Source link