How 2 Students With Disabilities Chose a College

[ad_1]

(This is the second article in a series on college applicants and the circumstances that shaped their choices this spring.)

But Fera, a high-school senior in Chevy Chase, Md., had to let go of that dream. “I had to make things as doable as possible,” she says. Doable would mean enrolling at a domestic college where she could get around easily and open doors by pushing a big button.

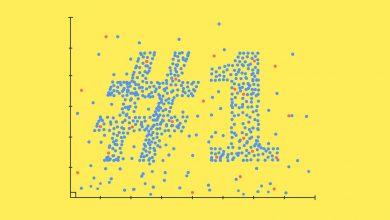

The thoughtful 18-year-old, who writes poetry and plans to major in psychology, will soon be among a large, often-overlooked subgroup: college students with disabilities. Though up-to-date numbers aren’t available, about 19 percent of all undergraduates in 2015-16 reported having a disability, such as a learning difference, attention-deficit disorder, or mental-health condition, according to federal data. Research from 2011 found that about 7 percent of students reporting a disability have a mobility impairment. Their numbers have surely increased since then, advocates for people with disabilities say.

Applicants with paralysis or impaired mobility ask the usual questions when considering a campus: Is this a place where I would feel comfortable and make friends, offering the major I need and all the other things I want? But they also must weigh a long list of other concerns, which can complicate — and limit — their choices. One student’s dream school might not be the most accessible campus on their list; a college that offers the best support services might not be the most affordable option.

Their decisions might come down to practical details. But also … a feeling.

Fera was in a car accident at age 8, sustaining a traumatic brain injury from which she fully recovered. But damage to her spinal cord left her paralyzed from the waist down. She has since used a manual wheelchair, a fact that shaped her thinking about where to enroll.

She got advice from Annie Tulkin, founder and director of Accessible College, who helps students with physical disabilities and health conditions make the transition to college. While federal law requires colleges to accommodate students with disabilities, those accommodations vary from campus to campus. The Americans With Disabilities Act sets “the floor, not the ceiling,” Tulkin says, for what students can expect from a college. Some institutions just stick to that floor; others go way above it.

Courtesy of Luna Fera

Tulkin encourages students to contact the disability-support office at each college on their lists to learn more about the services and assistance it provides. The conversations can be good practice for students who often have to advocate for themselves as never before, once they enroll in college. And those early interactions just might prove instructive.

Fera set up Zoom meetings with several disability-support offices, during which she rattled off questions. Would all academic buildings and gyms be accessible to her? Were there transport services she could use to get around if she had only a few minutes between classes? When it snowed, did sidewalks get shoveled promptly? Were the counters in dining halls low enough for her to reach food, or would someone have to help her?

This spring, Fera narrowed her list to three campuses. One was Goucher College, a small liberal-arts institution near Baltimore. She liked its study-abroad requirement and the fact that she could continue to learn Arabic there. Its proximity to home would allow her to keep the same doctors. And Goucher offered her a generous financial-aid package.

But Fera wanted to study in another state. She was impressed with the University of Pittsburgh, which she first visited last summer. It had all the right programs, and the campus felt welcoming. The disability-support office, she concluded, would provide her with a good safety net. And the city? She fell in love with it.

When Fera returned to the campus for an admitted-students day this spring, Pitt was at the top of her list. But then things changed.

His parents always thought that he would have to attend a college close to them. Schmick has a rare type of muscular dystrophy and uses a motorized wheelchair. He needs help bathing and going to the bathroom. His parents have always assisted him at home.

Schmick insisted on living on his own despite the inevitable challenges. “I’ve never been able to live away from my parents — not even, like, a day,” he says. “I just want to prove to myself that I can do it.” His parents supported his choice but weren’t sure where to begin. They didn’t have a road map for prospective students with his particular needs.

Last summer, his mother, Jean Schmick-Hopkins, searched online for “best colleges for students with disabilities” but found few in the Northeast. Schmick saw a Midwestern college on one list with a relatively low graduation rate. Not interested, he thought. He didn’t want to base his choice on accessibility alone. Strong academic programs mattered to him, too.

Jean Schmick-Hopkins

One day Schmick and his mother visited the disability-support office at a university in Maine to get some basic information. It didn’t go well. The people they met didn’t seem too interested in discussing his needs. Schmick-Hopkins found the experience off-putting. The staff, Schmick says, was “kind of rude, to be honest.”

As his senior year wore on, a big question loomed. Schmick would need a personal-care assistant, known as a PCA, in college: But how would that work? The ADA doesn’t require colleges to provide PCA services as an accommodation, so families must hire one themselves. At first, Schmick’s mother wasn’t sure that their health insurance would cover the cost. If they had to pay someone, say, $15 an hour out of pocket, it would add $20,000 a year, she figured. A potential deal-breaker.

Schmick got acceptances from a handful of colleges. One day he contacted the disability-support office at one of those institutions — and never heard back. “Some colleges, they don’t say it explicitly, but the vibe you get,” he says, ”is that they don’t want you.”

But Schmick got good vibes from Clark University, in Worcester, Mass., which had been his top choice all along. The university gave him a substantial scholarship. And just as important, he found the disability-support office attentive and welcoming. Schmick’s mother noticed that the university answered all her emails promptly.

Intangibles mattered. Schmick liked the engaging student who had led the campus tour when he visited — how she made a point of talking with him. Later, Clark sent him a handwritten note, which made him feel good.

When Clark accepted him, Schmick and his parents celebrated. Then his parents scrambled to figure out how to provide for a PCA. After making inquiries and sorting through some bad information, Schmick-Hopkins confirmed that the family’s insurance would cover the cost of a PCA, or at least a large portion of it, even at an out-of-state college. The news prompted her to shout with joy.

Schmick committed to Clark knowing there would be some trade-offs. The university offered him a double room with a private bathroom for the price of a single, he said. But it would be in a dorm for upperclassmen. Knowing that he wouldn’t live in a building with other freshmen gave him pause. And he would be the only undergraduate at Clark this fall who uses a wheelchair. But he decided that he was fine with all that.

There was much to like. When he visited the dining hall, he was glad to see bar-height tables: “A major selling point.” Low tables require him to bend over to eat, but tall ones allow him to raise his wheelchair and dine more comfortably. Also, the way Clark is situated will allow him to venture from campus on his own, without needing transportation.

Schmick, who figures he will major in political science, is a foodie who loves kabobs. As graduation neared, he pictured himself at Clark a few months later, heading downtown with friends, going to a restaurant, and ordering rounds of appetizers.

By choosing to go away to college, he had created such possibilities.

Fera asked Pitt to connect her with a current student who uses a wheelchair. But the university, she says, told her that it usually didn’t do that. Tulkin, the adviser who helps students with disabilities, encourages them to be persistent — and, in some cases, not to take “no” for an answer. So Fera asked again.

That did the trick. Fera had a helpful one-on-one chat with a student who uses a motorized wheelchair. She asked her about nitty-gritty details, like getting to and from the mailroom. She asked about the culture, whether students were accepting and inclusive of those with disabilities. Yes, she was told.

Fera also asked about the dorm that she would probably end up living in, because she had requested an en-suite bathroom. The student told her that the building might not be easily accessible because it was on a hill. She told Fera about an acquaintance who had some trouble getting around in her wheelchair. “I appreciated how real she was with me,” Fera says.

She had first visited Pitt on a warm, sunny day. But it was cold and drizzly when she returned this spring. She imagined herself turning the wheels beneath her and heading up a hill in bad weather. On the one hand, she believed the challenge would force her to become more independent, better at navigating a world that often makes things difficult for people who use wheelchairs. But her experience that day prompted her to consider another campus.

Students with physical disabilities and impaired mobility have ambitions. They carry the same angst and hopes as their peers. But each day they must confront many questions. Can I even get into this building? Should I go to the bathroom before attending the play? Can I make my way along this uneven, 19th-century brick walkway like everyone else?

Ultimately, Fera chose to attend the University of Oregon, which has been recognized as one of the most wheelchair-friendly campuses in the nation. Among the colleges she considered, it offered the most comprehensive support, she felt, for students with disabilities. When she visited the campus, she was impressed by its beauty. She saw wheelchair ramps that were not too steep — and students using them. The tacos at a campus cafeteria had just the right amount of spice. And the fact that her uncle lives in Oregon comforted her.

After all, moving from one coast to another would be a big deal. Since her accident a decade ago, Fera hadn’t gone out much. Then the pandemic sapped her motivation. “I became very introverted,” she says, “not getting to experience different things.” She felt like she had been inside a bubble for 10 years.

But college surely would bring her out of it. She was looking forward to having a lot of free time, going to concerts, striking up conversations with strangers in coffee shops.

On a recent Friday afternoon, Fera was at home among her many books. As her black cat, Bella, slept in her lap, she described how she was looking forward to making new friends on the other side of the country this fall. She imagined them messaging her at 1 a.m. to ask if she wanted to hang out. And she knew how she would respond: “I would just be like, ‘Yeah! Sure!’”

[ad_2]

Source link