Making a Home for Students With Autism

[ad_1]

True, he has autism, a developmental disorder that makes navigating college — and life in general — harder than it ought to be.

And yes, he failed the first time he tried college, dropping out after his mother died and he fell behind in his classes. “I crashed and burned,” Otto says, with characteristic bluntness.

But the fact that he made it to college at all sets him apart from the majority of people with autism, who enroll at rates well below most of their peers with other types of disabilities. That he got to try college a second time, this time with the support of a program for students with autism, makes him doubly fortunate.

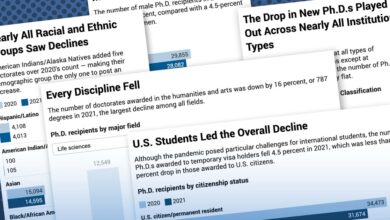

Each year, tens of thousands of students diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders graduate from high school, many with aspirations to attend college. Yet only about 100 colleges, most of them four-year institutions, have standalone programs for those students, according to an analysis by members of the College Autism Network. On average, the programs reach just 38 students each. More than a dozen states have no college at all with a program.

William DeShazer for The Chronicle

Yet as colleges stretch to serve a generation of students with increasingly complex academic, social, and emotional needs, programs designed to meet those needs are becoming more common. Campus autism programs, which have doubled in number over the past five years, are part of that growth.

It’s too soon to say what the programs’ long-term benefits will be for young adults with autism, who have some of the nation’s highest unemployment rates among people with disabilities. Because the programs are so new, they haven’t been rigorously evaluated, either individually or in comparison with one another. Though some, including Western Kentucky’s Kelly Autism Program (KAP), report graduation rates on par with the broader student population, it’s unclear which interventions are contributing to that success.

The goal “isn’t just to get autistic students to graduate and move on. It’s to make them feel like they’re actual people.”

Still, for Otto, at least, college isn’t just about the diploma that awaits at the end. It’s about autonomy and independence, the experience of “being treated like a respected adult and like my own decisions have value,” he says.

“The goal of KAP isn’t just to get autistic students to graduate and move on,” he explains in a meeting with his adviser, Kim Minton, this fall, “it’s to make them feel like they’re actual people.”

A moment later, Otto sighs, palm resting on his forehead, and grimaces. Kim asks what he’s thinking.

“I’m thinking about my life — and luck,” he says. Lucky to have an aunt who works in special education and picked up on his challenges early; lucky to have a school and parents who supported him; and lucky to get a second chance at college.

“I’m lucky, and that probably makes me the exception,” he says.

The most frequently cited figures come from a 2015 study that drew from a survey conducted in 2009, the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). It estimated that 49,000 autistic students graduated from high school in 2014-15, and 16,000 of them pursued postsecondary education within a few years of finishing, the vast majority at two-year institutions.

Given the striking rise in autism diagnoses in recent years, those numbers are probably much higher today, according to Bradley E. Cox, founder of the College Autism Network and an associate professor of higher education at Florida State University. Extrapolating from several data sets, he estimates that roughly 9,000 first-time, full-time freshmen with autism attend four-year colleges, and as many as 167,000 autistic students are enrolled across higher education.

The American Psychological Association defines autism as “a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by markedly impaired social interactions and verbal and nonverbal communication; narrow interests; and repetitive behavior.” Individuals with autism may have heightened, or suppressed, sensory systems, and difficulty with executive functioning skills like time management, organizing, planning, and emotional regulation. As many as half also have anxiety or attention-deficit disorder.

William DeShazer for The Chronicle

Because autism spectrum disorder encompasses a range of symptoms and severities, it manifests in highly individualized ways, as the students in Western Kentucky’s program illustrate.

Kayla, a junior, can’t stand the sound of a water bottle clattering to the floor in class, or an unattended scooter left beeping, and wears white-noise headphones to cope. Dante, a senior, sometimes struggles to read social situations, missing nonverbal cues. Ben, a sophomore, is working on time management. Most days, he’ll send his mom a picture of his breakfast to show her he’s up. If she doesn’t hear from him 40 minutes before class starts, she’ll call to check in.

While roughly a third of children with autism also have an intellectual disability, many of the students who make it to four-year colleges have average or above-average IQs, experts say, and might once have been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, a condition now subsumed under autism spectrum disorder. Students with mild to moderate cognitive impairments, or those who lack the skills to live independently, are more likely to attend open-access community colleges.

Yet while 70 percent of the students surveyed in 2009 said they’d attended a two-year college at some point or exclusively, just 10 community colleges offer autism programs, according to the College Autism Network.

On average, programs for students with autism charge between $3,000 and $4,000 a year, according to an analysis by the College Autism Network. While that price can put them out of reach for some low-income students, many are able to cover a portion or all the costs with financial aid, scholarships, or state vocational rehabilitation grants. That’s the case at Western Kentucky, where the state pays the full $5,000 cost for 90 percent of students, according to Michelle Elkins, who directs the autism program.

“Nobody understood the spectrum,” she says. When college administrators pictured autism, they saw severe cases — “mute boys rocking in a corner.”

Though there were autistic students attending college even then, many either weren’t diagnosed or didn’t register with disability services. Some who sought accommodations provided documentation for a different disorder — anxiety or a learning disability, for example, says Jane Thierfeld Brown, who directs College Autism Spectrum, a counseling and consulting firm.

Today, “you’d be hard pressed to find a campus that isn’t familiar with autistic students and their needs,” says Wolf.

Some of that familiarity stems from the fact that autism is much more prevalent today than it was 20 years ago — or at least more widely recognized. In 2000, one in 150 8-year-olds was diagnosed with autism, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; by 2018, that number was one in 44.

Meanwhile, secondary-school services for students with autism have improved, so they’re graduating from high school more prepared for the rigors of college, and better equipped to make decisions on their own.

As more students with autism make the transition from special ed to higher ed, the number of college programs serving them has grown from just a couple in 2000 to close to 100 today. Faculty members have become much better at recognizing and accommodating students with autism, program directors say.

Yet myths and misunderstandings persist. Among them: that autistic students are all math and science whizzes (they’re not — a lot love literature and theater); that they’re antisocial and uninterested in forming friendships or romantic relationships (they generally want friends — they just aren’t sure how to make them); and the biggest one of all, according to Wolf: that they’re disruptive and prone to outbursts in class (it happens, but it’s rarer than you think).

In an effort to combat those misperceptions, some college autism programs offer training for faculty, staff, and student groups. Some will act as mediators with peers and professors, helping smooth over misunderstandings.

Students “may just need some small adjustments — a little extra time on a test, or a less distracting environment.”

At Western Kentucky University, Elkins prepares professors ahead of time, emailing them a video about the program and a little information on each student’s needs before classes start.

Professors “think they’re going to have to make a ton of concessions,” Elkins says. They don’t realize that the students are “academically very capable,” she says. “They may just need some small adjustments — a little extra time on a test, or a less distracting environment.”

“Some don’t want anyone to know about their diagnosis,” she says. “Others are loud and proud.”

When Elkins sees her students on other parts of the campus, she doesn’t approach them. “It’s their story to tell,” she said.

That discretion includes deciding how to self-identify, and how much to disclose about their disorder to professors and peers. While some people with autism prefer identity-first language (“autistic student”), others favor person-first language (“student with autism”). Still others embrace the label “neurodiverse,” an umbrella term that includes other neurological or developmental conditions, such as ADHD and learning disabilities, and is associated with a social-justice movement that celebrates neurological differences.

William DeShazer for The Chronicle

In one recent survey of students with autism, participants said they typically revealed their diagnoses to professors and staff only to acquire formal accommodations, and waited to share them with peers. They described a tension between their efforts to “pass” as neurotypical, and their desire to embrace autism as part of their identity. Some researchers believe that for every student with autism who discloses their diagnosis to faculty and staff, there is one — maybe even two — who doesn’t.

College programs for students with autism vary in size and scope, but many offer some combination of coaching or advising, peer mentoring, career preparation, and social events. Common, but controversial, are “social skills” classes, which teach students how to interact in socially acceptable ways.

Such classes are fixtures in secondary schools, where they sometimes take the form of “lunch bunch” sessions with a paraprofessional. The most popular formal program, Peers,

developed by researchers at the University of California at Los Angeles, started with autistic adolescents but now has a version for young adults, too.

Proponents of Peers say it trains students how to navigate a neurotypical world, breaking down social interactions into concrete rules and steps, then having students practice those skills. Critics say Peers and similar programs are ableist, reinforcing the notion that autistic people must “mask” to fit in.

“Autistic people, in order to fit into society, have to pretend to be something that they are not,” says Sara Sanders Gardner, director of Bellevue College’s Neurodiversity Navigators program. “That takes a huge toll on them.”

Gardner, who uses “they/them” pronouns, speaks from personal experience. Years of masking their autism

have left Gardner with chronic pain and two autoimmune disorders. “It is soul-crushing to have to pretend to be someone you are not, all the time.”

Instead of offering social-skills classes, Bellevue’s program pairs students with peer mentors who help them develop a script for what they might say in a given interaction. Mentors don’t tell students what to say but walk them through a process of figuring it out for themselves, Gardner says.

Thierfeld Brown says that by the time autistic students reach college, they’ve typically had enough of social-skills classes.

“Most of the students I’ve worked with would say, ‘I could teach those classes,’” she says.

At Western Kentucky, students are required to take a semester-long social-skills class and can opt into additional skills groups, such as a recent one on dating. Peyton Collins, the program’s full-time mental-health counselor, readily acknowledges the sentiment among many students that they “have been social-skilled to death.” But he says students who were diagnosed at an older age — a population that includes many females — are often open to the training, “even yearning for it.” (A quarter of WKU’s current cohort is female this year, a record).

More universally popular among students are the regular socials — video-game night, Dungeons and Dragons night, the trip to the local coffee shop — and the weekly meet-ups with mentors in the student union.

But this week, Cady has brought a pack of Uno cards, so Uno it is. She deals the cards.

“Be prepared for friendships to be made and broken,” Otto warns.

Geoffrey lays down a red card. “Rojo, which is red,” he says. “I would have said it in Hungarian if I could. I went to Hungary this summer. I got a hat there.”

Over the next two hours of play, the students will debate which Marvel movie is the best, who played Spider-Man the best, and whether there has ever been a good DC Comics movie. The argument is animated but civil.

“These are the kinds of debates we have — movies, games, food,” explains Cady. “It helps us relate.”

“We’re humans, we debate about all things,” says Otto, tapping his head.

On one edge of the table, a couple steals quick kisses, their lips touching so briefly you almost wouldn’t notice if it weren’t for the brief smacking sound.

Someone mentions the Elvis movie, and Jaden, a mentor, asks how he died — was he really going to the bathroom? A nuanced discussion follows, until Otto distills it for the group: “Short answer: Died on toilet. Didn’t die going to the toilet.”

Halfway through the evening, Sean stands up to ask if the group would like to learn about a new historical figure. When no one objects, he shares the story of Ea-Nadir, a copper merchant in ancient Babylon who sparked the world’s first customer-service complaint. Beaming, he sits back down.

To his right, Geoffrey looks up foreign words — and profanities — on his phone. When the player next to him puts down a card that he likes, he throws down his own, shouting, “Spasibo! That’s Russian for ‘thank you.’”

At one point, the group falls silent for a moment. “I hate the silence,” says Jaden.

“It always happens every 20 minutes,” says Otto. “Just an observation.”

Someone throws down a card in a new color, and Sean exclaims, “My undying curses on people who mess with colors!”

“It’s Uno. Chill,” says Cady.

“I know,” Sean replies. “I just enjoy being dramatic.”

Eventually, the group starts disbanding. Some wave or mutter a goodbye, others wander off without saying much. Otto, one of two students in the program who commute to campus, is the last to leave, hoisting his backpack, computer bag, lunch bag, and water bottle and heading outside to meet his father.

“I love my family, but I live off-campus with them,” he explains. “Sometimes, it feels nice to be at a place where you can feel like a human being.”

Growing up, students with autism often have little say in their education. Decisions are made for them by their parents and teams of teachers and administrators, governed by Individual Education Plans, or IEPs. In many cases, parents oversee their social lives and schedules, too.

In college, students with autism have to advocate for themselves, seeking academic accommodations when they need them, and forming friendships independently. There’s no one to tell them when to wake up, when to head to class, or when to go to bed. For many, it’s a difficult, if welcome, adjustment.

“We’ve gone from parents orchestrating social activities for us, to now it’s up to us to reach out to a gaming club, to find out where there is a dance to go to,” says Michael John Carley, the facilitator of New York University’s program for students on the spectrum, who is himself autistic. “A lot of our folks get really overwhelmed.”

The transition to college can be tough on the parents of autistic children, too, says Minton, Otto’s adviser. “Sometimes, families can’t see them as adults,” she says.

When Otto started at Western Kentucky last year, his parents asked program staff to limit his screen time until he completed his schoolwork, Minton says. (Otto admits to a history of lying about finishing homework to get online). Instead, Minton and Otto worked out a plan to hold him accountable for getting his assignments done.

Sitting in Minton’s office for his weekly advising session, Otto sighs again, rubbing his eyes and grimacing. He’s thinking about luck, again, and about “scale,” he says.

“The people here are lucky to be here,” he says, slowly. “But I hope there would be a future where it doesn’t feel like the exception; it feels like the rule.”

[ad_2]

Source link