Priceless Sculptures Are ‘Literally Being Chipped Away’

[ad_1]

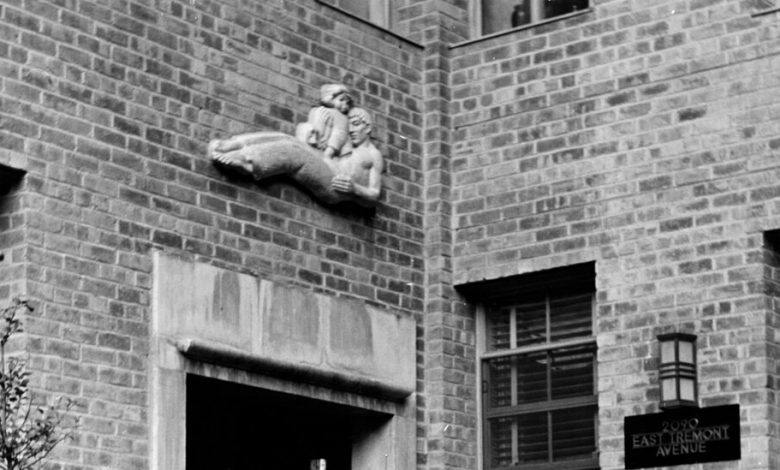

Among the more than 33,000 residents of Parkchester, the sprawling 1940s Bronx apartment complex, the most exuberant characters tend to hang out at the buildings’ entrances and corners: folk singers and firefighters, accordion players and harlequins, steelworkers and mermaids. There are exotic fauna as well, not typically found in such urban environs: gazelles, puffins, kangaroos and bears.

Vivid and three-dimensional, these neighborhood fixtures are whimsically crafted terra-cotta sculptures — more than a thousand of them, many colorfully glazed — embedded in the facades of Parkchester’s red brick apartment blocks.

These playful architectural ornaments, many by distinguished sculptors, have enlivened Parkchester ever since the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company built the middle-income housing complex starting in 1938. But in recent years some 45 of these signature artworks have vanished after being taken down by maintenance crews, infuriating many residents.

“They’re like the totems for the community, they’re the mascots,” said Sharon Pandolfo Pérez, a creative director for a multicultural advertising agency who spent her childhood in Parkchester and now runs the Parkchester Project, which documents on its Instagram page the removal of the distinctive sculptures.

Standing by the subway station at Hugh J. Grant Circle, Ms. Pandolfo Pérez pointed up at a brick tower, where a larger-than-life sculpture of a hose-brandishing firefighter in period garb jutted from the western corner near the building’s roof. For some eight decades, the building’s eastern corner was home to a companion firefighter, the pair serving as ornamental sentries at Parkchester’s southern gateway. But in 2018, workers removed the second firefighter and bricked up the wound in the facade as if the statue had never been there.

“When that first fireman came down, it was a sign that they just don’t care, because he’s one of the two you see when you come from the subway,” Ms. Pandolfo Pérez said. “It’s a sign that they are being taken for granted, and the people here feel taken for granted. This is working-class New York. If you’re taking that down, what’s that saying?”

In March, the Historic Districts Council, a citywide preservation group, announced the selection of the Parkchester Project for its annual Six to Celebrate program, which honors historic city neighborhoods and community groups that work to preserve them.

The council was impressed by the grass-roots efforts of Ms. Pandolfo Pérez, who, with crowdsourcing help from followers of her Instagram page — including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, now a Democratic congresswoman whose district includes Parkchester — chronicled the removal of several of the complex’s most high-profile sculptures between 2018 and last year. According to Ms. Pandolfo Pérez, the losses include larger-than-life sculptures of two firefighters, a muse, a skier and a woman carrying a flower.

The project’s inclusion in the Six to Celebrate program lends new momentum to a campaign, begun last year by prominent architectural historians, to persuade the city to designate the 129-acre Parkchester complex a historic district. The effort has attracted the backing of several preservation groups and elected officials.

Preservationists maintain that the clock is ticking.

“The complex’s unmatched set of polychromatic terra-cotta ornament — some 500 statuettes and 600 plaques — is, quite literally, being chipped away,” Roberta Nusim, president of the Art Deco Society of New York, wrote to the Landmarks Preservation Commission in November.

The destruction is the result, she wrote, of “sheer carelessness — the kind of carelessness that landmarks designation could prevent. The damage isn’t overwhelming — yet — and there is still time to act, but that time is slipping away.”

Nancy Johnson, a co-founder of the Parkchester Watch Group, an association for renters and owners of condominium units that advocates for quality-of-life improvements, said that there had been a lack of transparency about the sculptures from Parkchester’s management.

“I think it’s appalling that they’ve taken them down without a restoration plan,” she said. “We don’t know what they’re doing with them, if they’re being stored, or where they’re being stored, and this should have been discussed with the unit owners, with the community.”

The boards of managers of the Parkchester North Condominium and the Parkchester South Condominium said in a joint statement that 80 years of exposure to the elements had taken their toll on some statues and that “the masonry behind them needed repairs to be made safe. In those cases, the Parkchester North and South Condominium boards of managers have found it necessary to remove the terra-cotta elements, which are often too fragile to reinstall safely.”

The boards added that whenever possible, statues had been saved, carefully wrapped and placed in storage for safekeeping, an approach that would continue until a final plan was adopted. A spokesman for the condominiums would not say where the sculptures were being stored and declined to show them to a reporter.

But the boards pointed to the expense of caring for the sculptures. “We hope to be successful in saving and re-displaying as many as possible, if that can be done safely, securely and affordably for the community’s residents,” the statement continued. “Parkchester units have thousands of owners, and as a designated Naturally Occurring Retirement Community, many of those owners are on a fixed income.”

Preservationists say that landmark status is long overdue for Parkchester. In 1978, the landmarks commission’s staff wrote a Bronx Survey report that identified five potential historic districts, with Parkchester at the head of the list. Four have since been designated. But 44 years later, Parkchester remains unprotected.

“It’s one of the most important housing projects in America,” said Andrew S. Dolkart, a professor of historic preservation at Columbia University who worked on the 1978 Bronx Survey and later wrote the book on historic districts for the commission — the first edition of “Guide to New York City Landmarks.

Mr. Dolkart said that Parkchester and the contemporaneous Castle Village in Manhattan were the first housing projects in America to implement the modernist towers-in-the-park precepts set forth by Le Corbusier, the influential Swiss-born architect.

“Castle Village is five buildings, and it was for a solid upper-middle-class audience,” he added. “Whereas what makes Parkchester so important is that it’s an enormous complex and that it was built for less-wealthy people. It’s built for working people to create quality housing for them.”

The landmarks commission “is undertaking a detailed process of research and evaluation of this large complex,” Zodet Negrón, the commission’s spokeswoman, wrote in an email. “While much of the concern has been focused on the terra-cotta decorative elements, LPC must evaluate Parkchester’s architectural merit and historic significance in the context of housing complexes and our standards for designation.”

Easily the nation’s largest apartment complex when it opened, Parkchester was built by MetLife following the passage of a New York State law that allowed insurance companies to invest up to 10 percent of their assets in low-rent housing. With the eyes of the world on the venture, the company assembled an all-star team of design and building professionals led by the architect Richmond H. Shreve.

Known as the Board of Design, the group included Andrew J. Eken of the Starrett Bros. & Eken construction company, which had teamed with Shreve’s firm to speedily erect the Empire State Building.

Parkchester’s master plan was by Gilmore D. Clarke with assistance from Michael Rapuano, with whom he also worked on the master plans for the 1939 and 1964 World’s Fairs.

“Their impact on American space, primarily the New York metro area but by example, cities throughout the United States, was every bit as profound as the impact of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, if not more so,” said Thomas J. Campanella, a professor of urban studies and city planning at Cornell University who is writing a book about the pair. “Clarke basically was one of the inventors of the modern highway: the Bronx River Parkway, the Hutchinson Parkway, the Saw Mill Parkway.”

As the first major American example of towers-in-the-park urbanism, he added, the Parkchester plan became a template for urban-renewal public housing projects that would “fundamentally change the character and appearance of our cities from coast to coast, for better and worse.”

The pioneering complex was envisioned as a parklike community of more than 12,000 modern apartments on rolling land the company had purchased from the New York Catholic Protectory, which had dotted the area with orphanage and reform school buildings. The East Bronx site was bisected diagonally by Unionport Road, a constraint that Parkchester’s designers elegantly incorporated by widening the thoroughfare to 110 feet and crossing it with a second diagonal boulevard, dividing the complex into four irregular quadrants.

Building heights, too, were irregular, ranging from seven to 13 stories, with each quadrant’s structures arrayed in a variety of orientations, like rotated Tetris pieces, around a large central lawn. There was an intrinsic generosity to the design, which maximized light and air by placing the 51 residential buildings at least 60 feet apart and leaving three-quarters of the complex as open space. When a scale model of Parkchester was displayed at the 1939 World’s Fair, it “awed many a visitor,” Architectural Forum reported.

Not everything about Parkchester was generous, however. At the outset, MetLife restricted residency to white people. But after passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the complex was opened to all races. The 2020 U.S. Census found that its population was 35 percent Black, 33 percent Hispanic or Latino, 25 percent Asian and 3 percent white, according to Social Explorer, a research company. About half of the 12,271 units are owned by the Parkchester Preservation Company, whose management arm superintends the complex.

Parkchester was conceived as a city unto itself, complete with its own “downtown.” The main commercial district still has Streamline Moderne-style facades of colorful terra-cotta, including the first branch of Macy’s. Some store fronts are embellished with elaborate sculptures, like a rondel depicting a pair of women exchanging scandalous gossip.

The former Loew’s American, originally a 2,000-seat cinema and now occupied by a Marshalls, features some of the most charming, colorfully glazed terra cotta. Two harlequins flank the theater, while the building’s rear is decorated with a dazzling row of movie-character types, including a matador, a hula girl and a flamenco dancer.

“The time, care and money that went into” Parkchester’s ornament “is phenomenal,” said Susan Tunick, president of Friends of Terra Cotta and the author of “Terra-Cotta Skyline.” “It’s very special also because some of the pieces can be attributed to the sculptors. Terra cotta is usually unsigned, so it’s very important that the work was done by sculptors who signed their work rather than just workers in a terra-cotta factory.”

As a child, Ms. Pandolfo Pérez was enchanted by the ornaments. But her mother, a cook at a Bronx school, did not have access to information about them, said Ms. Pandolfo Pérez.

It was to fill that void for current residents that Ms. Pandolfo Pérez began the Parkchester Project, researching the development’s sculptors and corresponding with their descendants. She also bought small works by the artists through online auctions.

The complex’s visual smorgasbord of ornament was designed by nine sculptors and produced by the Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Company, which also made the cladding for the McGraw-Hill Building, including its celebrated crown.

Four of the sculptors —Raymond Granville Barger, Joseph Kiselewski, Carl Schmitz and Theodore Barbarossa — were described in Art Digest in 1941 as “prominent” artists who had done “important sculptural decoration” for the New York World’s Fair and for Parkchester.

Ms. Pandolfo Pérez said that Parkchester’s sculptures sparked her interest in art as a child and set her on a path to becoming a creative director. She hopes to have a similar effect on children, through a walking-tour app and school visits.

For many working-class people “who don’t get the opportunity to go to the Met, it’s attainable art, and it’s inspirational,” Ms. Pandolfo Pérez said of the ornaments. “That’s why identifying the artists is so important, because it gives residents a sense of pride to say, ‘The artist who made this sculpture had work in the Whitney Museum.’”

[ad_2]

Source link