Rejected

[ad_1]

“I feel many things,” he continued, “but not shame or regret. I am so proud of our work during our time at yale, and angry that this version of that work will come to an end, this end.”

Harry Haysom for The Chronicle

The statement reminded us how harsh that vote, which can upend — and even end — a scholar’s career, can feel to someone who’s spent more than a decade training and striving to succeed. Faculty members on the tenure track are the lucky ones, the minority who landed such jobs after laboring to earn their graduate degrees. But fortune is fickle. While Kraus told The Chronicle he was not ready to say more, five other scholars who’ve been denied tenure talked to us about the surprise, the grief, and the aftermath.

Alice Daer, denied tenure at Arizona State University in 2015

Alice Daer had considered the income loss. She’d thought about what it might be like saying goodbye to her research and how she would miss her students. But Daer hadn’t prepared for the way a single decision took away her very identity, the one she’d dedicated years to building.

“It’s really hard not to be Dr. Daer anymore,” she says. “There’s a prestige that comes with being a professor at an R1. That was really hard because all my friends were professors and now I have local friends who have no idea — and it’s weird because respect is not automatic.”

It’s been seven years since Daer learned she could no longer work at Arizona State University at Tempe.

Initially, she’d hoped to switch to a non-tenure-track role at a different ASU campus. But when she sat with English department leadership to discuss her options, Daer says she was told that the system has a rule that prevents professors who are denied tenure from working for the university again. (ASU’s current rule states that people who are denied tenure “are not eligible for rehire in any capacity” without approval of the provost’s office.) The finality of the information sent Daer into a “tailspin.”

“When you become an academic, you spend all of those years essentially building your brand,” she says. “It’s like owning a small business and your name is the name of the business.”.

Courtesy of Alice Daer

“You can feel bankrupt. … Those who survive, I don’t think survive on their own and without resources.”

Daer notes that she was fortunate to have a spouse to lean on. She considered going back on the academic job market but was reluctant to move her family. She felt that the communication and mentoring in her department were poor, particularly when relaying its decision to deny her tenure, and she feared facing the same problems at another college. In the end she decided to just start over.

She worked in content and digital marketing for a few years, then in 2018 launched a consulting company for academic writing with the help of a former colleague who’d also been denied tenure. She’s also on retainer with the online gaming company Twitch.

Daer says she’s been asked many times how she managed to start over. “Exercising that kind of humility is life-changingly difficult,” she says, so she tells those who come to her for advice to lean on as many support pillars as possible. She also advises moving — if that’s an option.

“It’s really, really hard to live next door to the university that took away my entire life,” says Daer, who stayed in Tempe. “It’s sort of like getting divorced, and then living across the street from your ex-husband or something and everybody in the neighborhood loves him.”

—Sahalie Donaldson

Charles A. Laughlin, denied tenure at Yale University in 2005

When conversations about tenure denials made waves on academic Twitter last week, Charles A. Laughlin was brought back to the disorientation and confusion he felt at Yale University more than 15 years ago.

Laughlin had been hired as an assistant professor in 1996, his first job out of his Ph.D. program at Columbia University, and was promoted to associate professor a few years later when the East Asian languages and literatures department renewed his contract for the second time.

He was up for tenure during his ninth year — on the clock Yale used at the time — but did not think a decision had been made when he set up a general meeting with his department chair. There, he says, he was informed that the department had already looked over his file and decided to deny his bid, citing Laughlin’s unpublished second book as the official reason.

The news came as a shock.

While Laughlin understood that publishing a second book was a condition of tenure, he had assumed he’d be given flexibility, as he’d completed the manuscript and was already speaking with a publisher. He’d also been asked by department leaders to head a fellowship program for students studying languages in East Asia and to serve as the department director of undergraduate studies — so he’d thought he had good relationships with colleagues.

He doesn’t remember any conversations that indicated his case might not go through, he says. “It wasn’t like I dropped the ball on the 1-yard line either. Everything was in place.”

He says he was also told of factors — a lack of familiarity with his field, and some misunderstandings — that might have influenced the department’s decision.

Courtesy of Charles Laughlin

“I believe in most cases that people sitting around the table are carefully reading the materials. But they can be so easily influenced by a letter here, a review here, a faculty member complaining there — these relatively small factors can have such a big impact,” Laughlin says.

Yale has a reputation of not hiring internally for tenured positions. Laughlin recalls a faculty meeting where the provost appeared very proud to report that one out of five tenured faculty at the university had risen from within its ranks.

“You can almost say there was a culture of being psychologically prepared for being denied for tenure among junior faculty in the humanities, at least that I knew at Yale,” Laughlin says.

Still, he thought about filing a grievance. In the end, he decided not to. He says he wouldn’t have wanted to continue working in a department with colleagues who were in favor of his leaving, nor did he want to burn bridges with the university and risk squandering other opportunities.

One opportunity arose a few weeks later, when Laughlin was asked to head one of the university’s study-abroad programs in Beijing. He promptly accepted. A few years later, the University of Virginia offered him a tenured full professorship and endowed chair in East Asian studies. He’s been there ever since.

Laughlin knows he’s luckier than most people who’ve lost their tenure bids. Still, lingering questions about what happened and why have remained with him.

“It bugs me,” he says. “I work really hard to get along well with the people I work with and to do a good job in my groups. If there’s something that I don’t know about that I’m not doing right, it needs to be communicated to me.”

—S.D.

Gillian Marshall, denied tenure at the University of Washington at Tacoma in 2021

Gillian Marshall is what some might describe as an academic star. She attended the University of Washington at Seattle’s highly ranked graduate program for social work. She was mentored by researchers known nationally and internationally for their work on aging and mental health. Her first job after receiving her doctorate was at Case Western University — another top 10 school for social work.

When Marshall moved to the University of Washington at Tacoma in 2015 she brought with her several hundred thousand dollars in grant funding, she says. Two years later, she had more than a million dollars in grants.

“I did everything, everything that I was supposed to do,” Marshall says.

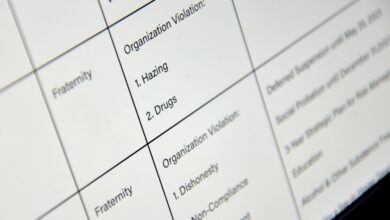

But last spring, the university rejected her tenure bid. The reason she was given: two years of poor teaching evaluations. Marshall — pointing to peer reports that called her teaching “exemplary” “inclusive,” and “respectful” — says the decision was racism, pure and simple. She decided to sue.

“I trusted a system that said if you work hard and you pull yourself up by your bootstraps, and you do what you’re supposed to do, that you will be rewarded in the end, and I was not,” she says.

Courtesy of Gillian Marshall

What galls Marshall in particular is that teaching makes up just a small part of her responsibilities, because under a prestigious Mentored Research Scientist Development Award award from the National Institutes of Health, 75 percent of her time must be devoted to research. The poor evaluations came from the one course she had taught both of those years.

Through the lawsuit, Marshall was able to get copies of outside evaluators’ assessments of her research. One wrote that the “quantity and quality of work place her in the top 10-15% of Assistant Professors in gerontology across the social and behavioral sciences.” Another commented on her “impressive funding record” and presentations of her research at numerous conferences.

Leah Hollis, an associate professor at Morgan State University, testified as an expert witness for Marshall that her treatment by the University of Washington constituted academic bullying.

“That’s exactly what happened,” Marshall says. “They were bullying me to get out. They denied me tenure because I am a Black woman, and I am a successful Black woman.”

In its motion for summary judgment, the university said “racism had nothing to do” with the decision: “The Court should not accept Dr. Marshall’s invitation simply to assume, as Dr. Marshall apparently does, that every perceived workplace slight she claims she experienced is racially motivated or actionable.”

The court agreed, dismissing the lawsuit in November. But Marshall has not given up: She has filed an appeal.

Marshall, who is still working at UW, says Black women in the academy face discrimination all the time, but not everyone has the stomach to fight it. “I think there is a real fear about speaking up, because it’s like you then have a scarlet letter on your back,” she says. “It’s expensive to pursue this, it’s difficult, it’s taxing.”

She has a year to find another job, in a context that makes that psychologically difficult. “You’re working in an environment where people don’t support you and you still have to get up and do your job,” she says.

“I honestly believe if I was a white man, I would have been tenured no problem.”

—Abbi Ross

Crystal Colombini, denied tenure at the University of Texas at San Antonio in 2019

Crystal Colombini was a new Ph.D. and already a mother of two children — a 2-year-old and a 4-year-old — when she joined the English department at the University of Texas at San Antonio in 2012.

She felt lucky to get a job so quickly and even luckier to be on the tenure track.

But soon after she arrived at the university, she found out she was pregnant with her third child. She and her husband had needed fertility treatment to have the first two, so she hadn’t even thought another pregnancy was possible.

Kristin Werthman

And while she was looking forward to the new baby, that made working toward tenure seem all the more daunting. Finishing her Ph.D. while taking care of two children had been hard enough.

“I knew I would struggle,” she says.

But she was determined. She longed for the freedom that tenure would provide, a status that would let her “intellectual development progress at its own rate.”

She says to keep up she went past what she considered her “max capacity.” When her baby was born, Colombini hadn’t yet spent a full year at the institution, so wasn’t eligible for paid maternity leave.

“My years on the tenure track really overlaid with the toughest years of my family,” she says.

Her biggest challenge was the book she needed to produce, on the rhetoric of homeownership. She says the pressure was particularly intense because the university was striving to become a Research 1 institution in the Carnegie Classification (a status it has since gained). But as a junior faculty member, Colombini says she did not feel supported.

Despite all that, when it was time to go up for tenure, she felt like she was emerging from her hardest years. She had made good friends and connections across the university, her momentum was building, she had projects in the pipeline that were getting accepted. Her book wasn’t finished, but she had gotten “great preliminary feedback” on it from a publisher.

So when the department denied her tenure application because her book wasn’t far enough along, it was “devastating.” The decision gave her one year to find another job.

“It’s the thing you have nightmares about,” she says. “It’s not that I didn’t fear that that would happen, but I felt hopeful that I’d done a good job and that my colleagues would want to keep me.”

Colombini felt like her department had decided ahead of time that she wouldn’t be successful. But with the positive feedback on her book pushing her forward, she decided to appeal. She was convinced that if she could land a book contract, everything would be OK.

According to the university, “appeals should be made only in cases where new, compelling information relevant to a promotion decision has become available” since the completion of the review, like receiving competitive funding or a prestigious award.

The tenure denial plagued her with a sense of inadequacy. Still, she says she worked 100-hour weeks on her appeal for nearly six months, barely seeing her family during that time.

She lost hope when she realized that her case was being considered by the same people who had seen it before.

“There was no mechanism for a different perspective on the situation,” she says. “It didn’t feel to me that by the time it went back for the appeal that there was any possibility that people would reverse a decision, no matter what.”

The appeal was denied “unceremoniously,” she says. At that point, she was “ready to let go.”

One of the hardest parts for her was breaking the news to her family. She knew her kids were happy in San Antonio and that her husband had a good job.

And she felt alienated in the department. None of her senior colleagues spoke to her for months after the vote, she says, and they seemed to pretend they didn’t see her walking past them in the hallway. Colombini leaned on friends and colleagues who had helped her though the process, some of whom had written letters they said supported her tenure case.

She had moments of relief while teaching her students but all other aspects of her department life were just “painful.”

In 2020 she found a job at Fordham University, where she was granted tenure upon hiring. Now, she wants to be as open as possible about her experience and serve as a mentor to people who are going through the same thing.

“I think the experience is so lonely and it’s so disenfranchising that for me if I share my experience and it makes somebody out there feel less alone, then I feel like I’m sort of doing my part as a citizen, as a mentor,” she says.

—Oyin Adedoyin

Leigh Gruwell, denied tenure at Auburn University in 2020

Leigh Gruwell, an associate professor of English at Auburn University, was denied tenure in 2020. After the years and money she spent on graduate school and the upheaval of moving her family and her partner to Auburn, she still finds it difficult to get over the feeling that her university betrayed her. “You invest so much into your career, into your institution, into your colleagues and into your students.” Now, she says, she doesn’t identify as strongly as an academic. “It’s just my job.”

Gruwell recently shared her story on Twitter.

Courtesy of Leigh Gruwell

According to her department’s guidelines for tenure, Gruwell needed at least six published articles or a book under contract by the fall of 2020. By that spring, she had four published articles and a preliminary contract with Utah State University Press based on her book proposal. Gruwell says she was on track to get her book under official contract in the fall, but Covid-19 interrupted her trajectory.

She sent her manuscript out for a second round of reviews in March 2020, but disruptions caused by the pandemic delayed that round, and ultimately the press assigned Gruwell an entirely new set of reviewers. That meant she had little chance of receiving a final book contract by her department’s deadline.

At the time, Auburn faculty members in their first through fourth years at the university were eligible for Covid-related extensions on their tenure timelines. Gruwell was in her fifth year.

Auburn is unusual, though: Faculty members get two shots at tenure within seven years before they are terminated. By 2021, Gruwell’s seventh year, she had received an official book contract. While she knew the university almost never reversed departmental decisions, she decided to try again and was granted tenure without contention.

Even so, Gruwell struggles to sort through the emotions from that initial denial. “By the letter of the law, no, I didn’t feel like it was necessarily unjust, but it felt unfair to not take into account the context of the pandemic,” she says.

Gruwell knows that her experience isn’t unique. “I don’t think this is about me personally, or about my school specifically,” she says. Rather, “… it points to larger failures that have always existed in academia and that have been amplified during the pandemic.”

—Chelsea Long

[ad_2]

Source link