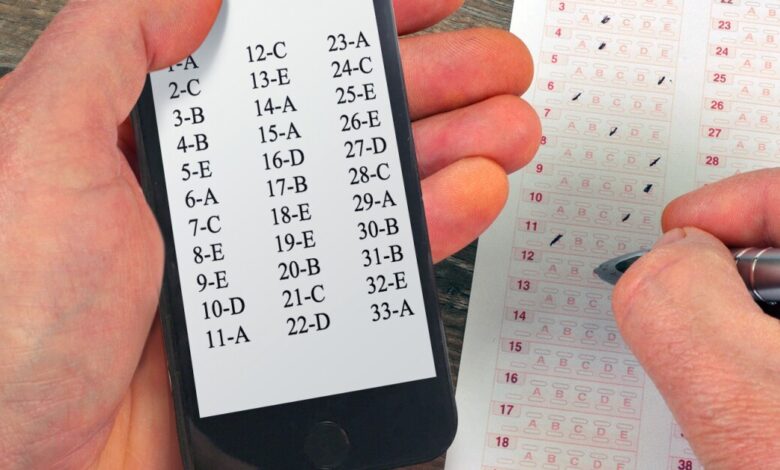

Some Students Use Chegg to Cheat. The Site Has Stopped Helping Colleges Catch Them.

[ad_1]

Chegg is no longer providing student information to colleges conducting honor-code investigations through the platform.

The company, along with competitors such as Course Hero and Bartleby, markets itself as a resource for college students seeking homework help and tutoring. These companies have cultivated reputations, though, as conduits for cheating, as some students misuse the platforms to seek answers to exam questions and other assignments.

Faculty members say Chegg, which as of August reported 5.3 million subscribers, used to be an industry outlier in its willingness to share user-level data with institutions on a case-by-case basis — including IP addresses, user names and emails of those who had posted exam questions or even reviewed answers — as an accountability tool to deter cheating.

“Chegg was the only site that was willing to actually engage with me,” recalled Ajay Shenoy, an associate professor of economics at the University of California at Santa Cruz, who used Chegg’s honor-code investigations process in early 2020 to identify three of his students who’d posted his exam questions on the platform. “It made me feel like Chegg might actually care about academic integrity.”

According to Chegg’s honor-code policy, which was updated on August 8, the company cooperates with colleges, but — in the interest of student privacy — is now providing only the date and time stamps of when questions and solutions are posted. Chegg officials declined to outline the company’s past disclosure practices.

Chegg was the only site that was willing to actually engage with me.

Three faculty members at different institutions told The Chronicle that Chegg had provided information on suspected cheaters to them in the past; the company’s current privacy policy, last updated in October 2021, also still notes: “We may disclose your information, including personal information upon request of an academic institution connected to an investigation into academic integrity.”

Candace Sue, head of academic relations at Chegg, said the company’s policies have been evolving to meet user expectations. “The views on privacy in regard to technology … they are changing, and we want to be in line with those views,” Sue said.

Student privacy has become an increasingly pervasive concern as colleges’ and students’ technology use grows; just last month, a district judge in northern Ohio ruled in favor of a student who said being asked to conduct a scan of his room — a common component of online proctoring software — violated his Fourth Amendment right to protection from “unreasonable” government searches.

The policy shift is nonetheless disconcerting to those like Shenoy and David Rettinger, director of academic-integrity programs at the University of Mary Washington, in Virginia. “I’ve said over and over again that there’s nothing wrong with commercial homework-help sites as long as there’s transparency and accountability,” Rettinger said. “This is a move directly in the opposite direction of that.”

While those in academe are split on how seriously to take cheating, Rettinger and Shenoy say the implications are more far-reaching than whether a student learns the content in a given course. “We rely on higher education to prepare people to be participants in our society” and to solve problems, Rettinger said. “I can’t think of any career where I would want somebody whose lesson in college was, ‘I’m going to take the easy way out.’”

There can be tangible damage, too. In Shenoy’s economics classes, for example, exams are graded on a curve — meaning students who cheat may indirectly lower the grades of their peers who are completing work honestly.

To Shenoy, Chegg’s decision feels like a business calculation. The shift more closely aligns Chegg’s policy with that of its competitors, which, faculty members told The Chronicle, in their experiences don’t disclose any user data to colleges, unless under subpoena. The move also comes as the company has seen more than a 70-percent drop in its stock price in the last year, though subscriber numbers appear stable, growing about 9 percent over a similar period, according to quarterly financial reports. Subscription costs start at $15.95 a month.

It’s “like they’ve decided that it’s not profitable to turn in cheaters,” Shenoy said.

Officials at Chegg took issue with that notion, pointing to ways the company invests in academic integrity: Trainings for its free-lance experts who post solutions to questions on the platform to recognize abuse. An advisory board of four faculty members from institutions such as the State University of New York and Southern New Hampshire University, along with a student-government leader. Its practice of removing violators of its honor code from the site. (The company declined to share the proportion of its users removed from the platform for violations.)

Candace Sue and Nina Huntemann, chief academic officer at Chegg, also highlighted a free “preventative” tool called Honor Shield. Through the tool, faculty members submit their exam questions, and Chegg blocks those questions “across our site, worldwide” for up to 24 hours to “protect their questions during the period of their exam,” Sue said. She noted that Chegg has no license to these submitted materials, and deletes them from their records once that period expires.

“It’s an absolute betrayal of a relationship that’s really important in the classroom between a student and a teacher if cheating happens,” said Huntemann, a former college professor. “So from our perspective, we want … a much more proactive approach to academic integrity.”

Shenoy said there’s a lot more trust needed between faculty members and Chegg, though, for a tool like that to be successful. “Faculty members who are writing an exam, we keep these things so under wraps. Even back when I had paper exams, it was like, ‘Can I trust the people at the copy office?’” he said. “So the idea that I’d give [Chegg] my exam … that’s absurd.”

Chegg declined to share the number of professors who have submitted materials through Honor Shield since the project was started in early 2021.

Rettinger, who is also a professor of psychological science, says he and his colleagues are curbing cheating in other ways.

There’s “low-hanging fruit” — he doesn’t reuse test materials, for example. Instead of major exams, he offers weekly quizzes for fewer points, lowering the stakes. Students help generate quiz questions on Sunday nights as homework, helping ensure they view the tests as “fair” and relevant. For research papers, students have autonomy to pick topics that they’re interested in.

“I can’t stop students from cheating” all the time, Rettinger said, so “the goal is to not make it desirable. I want them to want to do the work.”

[ad_2]

Source link