The Far-From-Perfect Data in the Rankings

[ad_1]

“Every time I’ve gone to that session, it’s been standing-room-only and people leaning in the door,” said Jeffrey A. Johnson, director of institutional research and effectiveness at Wartburg College. Conference-goers always ask tough questions, said Todd J. Schmitz, assistant vice president for institutional research for the Indiana University campuses. But Morse’s audience is rapt: “He has this room of 300 people hanging on his every word,” Johnson said.

The scene captures the complicated relationship between colleges’ data submitters and U.S. News, the best-known college-ranking system in the United States. Many resent the time and oxygen the ranking takes up. After The Chronicle asked to interview her, Christine M. Keller, executive director of the Association for Institutional Research, conducted an informal poll of the group’s members about their views of U.S. News. One major theme: Answering the magazine’s survey requires too many resources, a situation they see as taking away from internal data projects that contribute more to student success than rankings do. Yet they know that responding to the survey is an important part of their jobs, and often campus leaders are paying close attention.

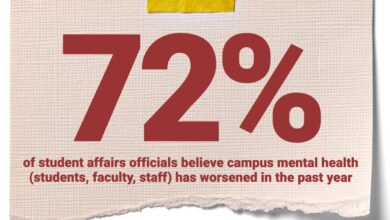

Recently that relationship has undergone renewed scrutiny, as rankings-data controversies have piled up. First, a former dean of Temple University’s business school was sentenced to 14 months in federal prison for leading an effort to inflate statistics his school had sent to U.S. News. Then a Columbia University mathematics professor publicized his belief that his institution is sending inaccurate data to Morse and his colleagues, a contention Columbia has denied. Finally, the University of Southern California pulled out of the rankings for its graduate program in education because it discovered it had submitted wrong data for at least five years.

The headline-grabbers are the latest in a decades-long history of scandals about colleges gaming U.S. News and unintentionally sending inaccurate data to it. Every few years, it seems, another incident comes to light. Criticisms of the rankings have also been longstanding, but there’s been some fresh attention since the popular journalist Malcolm Gladwell covered them on his podcast last year.

Willis Jones, an associate professor at the University of Miami who studies higher-education leadership, has noticed more of a social-justice bent to rankings criticisms lately. Increased societal awareness of historically Black colleges and universities highlighted that rankings are “one of the many things that were creating disparities among HBCUs versus predominantly white institutions in state funding and things like that,” he said.

Another observer, Akil Bello, director of advancement for the National Center for Fair and Open Testing, an advocacy group known as FairTest, has noticed more critiques of rankings methodologies making it into the mainstream. “There are some cracks being created in the belief that there is an objective foundation to the creation of the rankings,” he said.

As the college staffers typically responsible for gathering and submitting the high-stakes data, institutional researchers are on the front lines of this much-scrutinized process. And while outright lying may be relatively rare, there’s always human error, plus ample room for interpretation in the U.S. News questions. That ambiguity can create incentives to finesse the data in a way that makes one’s institution score better in the magazine’s rubric.

“Not one of them had a clean audit,” Larmett said. Colleges were making unintentional mistakes, often as a result of software systems not working well together, the timing of data pulls (at what point in the year enrollment is counted, for example), and human errors in data entry.

“High risk” statistics, where Baker Tilly auditors often saw problems, included the number of applicants, admitted students’ test scores and GPAs, and faculty-to-student ratios. Test scores can be problematic if colleges rely on numbers shared by applicants rather than by testing companies. And who counts as a faculty member or a student can be defined in many ways, depending on who’s asking.

The differences between what colleges reported and what Baker Tilly found were generally small, Larmett said. But you never know what will be enough to give an institution a lower or higher ranking than it deserves, she said, given that U.S. News doesn’t disclose exactly how it weights survey answers in its rankings.

Even with perfect quality control, two institutions may still count the same number in different ways.

“There’s this overarching tension when you have any type of survey, ranking, or data gathering, where you’re trying to capture the universe of higher education,” Indiana’s Schmitz said. “You’ve got a panoply of different types of institutions, and yet you’ve got one survey instrument and set of definitions that try to be at the same time sufficiently vague and sufficiently specific, so that institutions can see themselves in these survey questions and they’re not totally off the rails.”

“At the same time, there is a lot of interpretation that happens with the U.S. News & World Report survey questions,” he added. “It is up to folks like myself in the profession, who know what the gold standard should be.”

The U.S. News survey appears to try to provide plenty of guidance. The 2022 main survey, for example, devotes several paragraphs to defining “faculty” and “class section,” concepts that feed into faculty-to-student ratios and average class sizes, both influential factors in a college’s ranking.

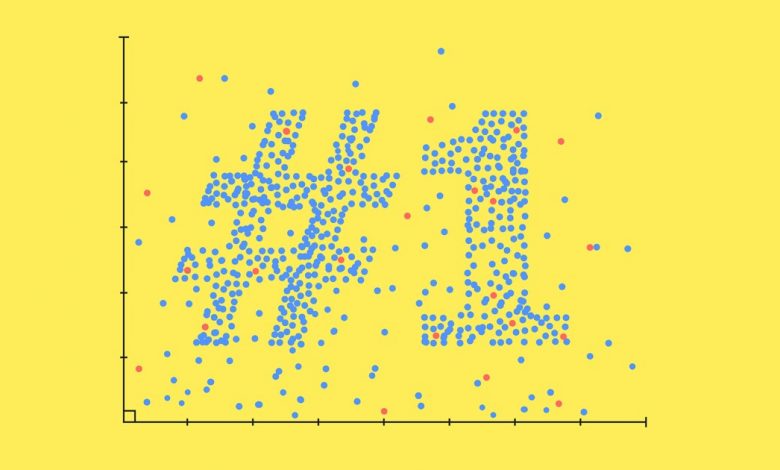

Tyler Comrie for The Chronicle

Nevertheless, Schmitz said, people could interpret those questions differently. At one point, the survey asks for the number of faculty members who “teach virtually only graduate-level students.” If there are one or two undergraduates in a class, he said, does that count as “virtually only” graduate students? What if the undergraduates are auditing the class and aren’t receiving credit?

When and how to measure class sizes bring yet more ambiguity. “You can defensibly use the start of the semester or the end,” Schmitz said. “You could also artificially limit section seating caps.” U.S. News calculates a score for class sizes using the number of classes that fit into different buckets, including how many classes have fewer than 20 students. Thus a seating cap of 19, rather than 20 or higher, for some classes could raise a college’s score.

One question of interpretation loomed large in the analysis by Michael Thaddeus, the Columbia professor who challenged his institution’s place in the rankings. Columbia classifies patient care provided by medical-school faculty members as instructional spending, a decision the university defends on the grounds that the professors may be training students while seeing patients. Still, it’s unusual in the field to consider such expenses as instructional, said Julie Carpenter-Hubin, a former assistant vice president for institutional research at Ohio State University, who retired in 2019.

The inevitable gap between guidance and practice leaves a lot of responsibility on data-gatherers’ shoulders. “You can make those decisions well and defensibly, or you can make them in ways that are indefensible,” Wartburg’s Johnson said. “What you can’t do is simply fall back on the rules and say, ‘Yep, the rules tell us exactly what to do,’ because they don’t.”

“I don’t want to say that anybody would ever pressure folks to misreport,” Carpenter-Hubin said. Instead there can be pressure to “find the best possible way of saying something.” (She emphasized that was not the case at Ohio State; she was speaking generally, she said.)

They are imposing their framework for how colleges and universities should be ranked on everyone else.

“The incentives are in place for everyone to want to put their best foot forward to describe their institution in the most favorable light” to U.S. News, said Keller, from the Association for Institutional Research.

One interviewee, however, said she had little experience of the kind of data shenanigans that make the news.

“This is probably a point of privilege,” said Bethany L. Miller, director of institutional research and assessment at Macalester College, “but I don’t know a lot of people who are nervous about reporting data.”

She pointed to counterpressures at work to keep people honest: the reputational hit colleges take when data misreporting comes out; fines and potential prison time for misreporting to the U.S. government, if not to a private company like U.S. News (though the Temple case shows that lying to U.S. News can bring prison sentences too); and the Association for Institutional Research’s ethics code.

The institutional researchers The Chronicle interviewed said they thought their peers did the best they could, had quality-control checks in place, and made only small mistakes, if any. Institutional researchers’ beef with U.S. News isn’t the data’s integrity. “It’s more the fact that they are imposing their framework for how colleges and universities should be ranked on everyone else,” Keller said. “In the end, the data is likely not perfect, but it’s how the data is being used that is the issue for me and a lot of my IR colleagues.”

Meanwhile, despite the criticism, the rankings remain as important as ever to some audiences. College marketing teams still tout high rankings, and boards of trustees still fret when their standings fall, Jones, of Miami, said. The share of first-year students at baccalaureate institutions who say that “rankings in national magazines” were “very important” in their choice of college has hovered at just below one in five for more than a decade, although it fell to about one in seven in 2019, the latest available data.

And the assumptions behind the rankings still shape the way people talk about colleges. “How do you unring the bell of the socially accepted rankings?” FairTest’s Bello said. “That’s the biggest challenge right now — is that the ‘These colleges are good’ and ‘These colleges are bad’ has entered the ether of the higher-ed admissions landscape.”

[ad_2]

Source link