The Long Shadow of Jerry Sandusky

[ad_1]

This time, it was the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor.

About 200 students had gathered last month in front of the president’s house to demand accountability for years of alleged sexual abuse by a university doctor. A law firm’s investigation revealed this year that university officials knew of the abuse by Robert Anderson, who died in 2008.

“This university has been mired in sexual assault, abuse, and cover up, and we say, No more,” Jon Vaughn, a former student and football player who went on to play for the NFL, said at the demonstration. Vaughn and hundreds of other former students say they were molested by Anderson.

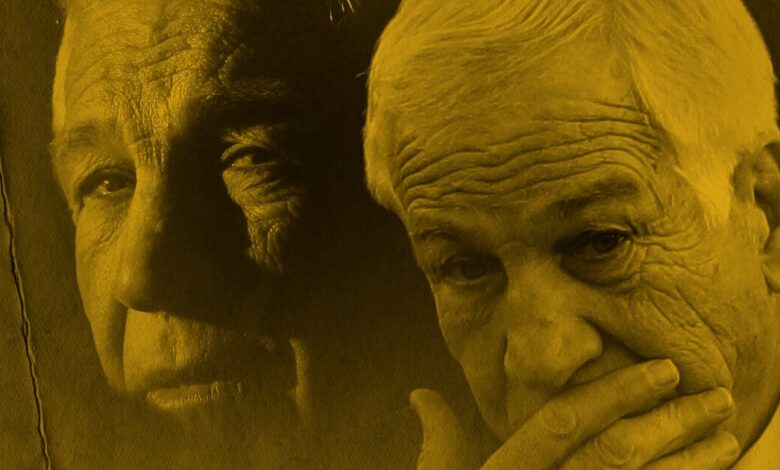

Bill Pugliano, Getty Images

The former Michigan students were joined by survivors of Larry Nassar, the convicted Michigan State University doctor. In 2018, more than 150 women testified that Nassar had sexually assaulted them. He went to prison for life, the university’s longtime president resigned, and investigations continue today into how such abuses could have occurred.

Not long ago, horrific cases of serial sexual abuse on college campuses rarely reached the public’s notice. That changed a decade ago this week, when prosecutors accused Jerry Sandusky, a former assistant football coach at Pennsylvania State University, of having sexually assaulted young boys over a 15-year period. He was convicted of 45 counts of sexual abuse and given an effective life sentence. Three top Penn State administrators were later convicted of misdemeanors because they did not report Sandusky to the police, including Graham B. Spanier, the institution’s president of 16 years, whose reputation had once seemed unassailable.

A decade ago, Sandusky’s story was that of a bad actor. Now, it’s clear he was a harbinger.

In the years since his indictment, a series of revelations about sexual abusers who made their careers at colleges and universities has rocked higher education. As the stigma around coming forward about sexual assault eased slightly, a culture of secrecy that protected perpetrators — enabled in part by the conventions of the academy — also began to erode.

In addition to Michigan State and the University of Michigan, there was Ohio State University, where a wrestling team physician who died in 2005 was accused of having sexually abused athletes. At the University of Southern California, a gynecologist was accused of sexually abusing hundreds of students who were his patients. The university agreed this year to pay $1.1 billion to the former patients, a record for college sexual-abuse cases. And at the University of California at Los Angeles, another gynecologist was accused of sexually harassing patients. UCLA paid his former patients $73 million, according to the Los Angeles Times. Both California doctors have pleaded not guilty.

The cases have drawn national attention and involved years of litigation. They have forced victims to become public figures, testifying sometimes more than once, in front of cameras and in front of Congress, as some of Nassar’s victims have done. There will be more such cases.

Jeff Kowalsky, AFP, Getty Images

What made the last decade ripe for years-old allegations of abuse to come to light? When Jennifer Freyd began researching sexual violence in the early 1990s, it was still an obscure field of study. Since then, the University of Oregon emerita professor said, it has grown in fits and starts. In 2010 and 2011, campus sexual assault gained a new level of attention with the issuance of the Obama administration’s “Dear Colleague” letter. In 2017 and 2018, the #MeToo movement pushed sexual harassment and other forms of workplace abuse to the fore.

Moments of revelation are important, said Freyd, who founded Oregon’s Center for Institutional Courage. They help people understand phenomena that have long been taking place.

“Coach sexual abuse, priest sexual abuse, medical sexual abuse, that’s been going on for as long as people have had those roles,” Freyd said. “What’s changed is now people are starting to see it, talk about it, be outraged by it.”

The data that researchers have been compiling over the past decade have helped prove to the public that sexual violence “is very, very real,” Freyd said. Student activists, she added, who have more independence than employees, have been important in bringing these issues into the public’s consciousness.

But greater public awareness of a systemic problem isn’t the only driving force behind these flashpoints, Freyd said. “There’s much more distrust of our major institutions,” she said. “It’s good in the sense that people have their eyes open and see more clearly the way institutions are failing them.”

Universities tend to be disincentivized in addressing these issues.

Healthy, trusted institutions are necessary for a functioning democracy. But the forces preventing colleges from making meaningful changes to prevent abuse are powerful, researchers said in interviews.

“Universities tend to be disincentivized in addressing these issues,” said Sarah L. Young, an associate professor of public administration at Kennesaw State University. There are several reasons, but one is the prominence given to reputation and prestige — as sometimes expressed in college rankings, she said. “Sexual scandals can really hinder those rankings,” making it less likely that leaders will report on their own institutions.

She listed policies that make it more difficult for people at universities to come forward. Decisions about how an alleged perpetrator should be punished are often complicated by circumstances that tip the scales against accountability. A department chair or dean might know an offending professor personally. Or they might be influenced if the professor brings in a lot of outside funding.

Many people at universities, notably professors, work relatively independently from their coworkers in other parts of the institution, said Kimberly Wiley, an assistant professor of nonprofit leadership and community sciences at the University of Florida. As a professor, her scholarly output is visible to coworkers when she publishes something, but they don’t necessarily how she interacts with students. At a nonprofit or company, there’s often more oversight, she said.

Even when university leaders are motivated to make big, cultural changes in how they respond to sexual violence, it’s hard to do because of how decentralized campuses are, Young said. And individual units — like a specific college or the athletic department — may hold outsize influence with leaders who make decisions.

John C. Manly, a lawyer who represents victims in many of these cases against universities, said that decentralization carries another problem. “At many of these universities there’s just nobody in charge,” he said. “You have these boards of trustees who owe allegiance to nobody. Their fiduciary obligation — that’s all code for, It’s all about the money.”

Something else that has changed since Sandusky’s arrest is that people are more willing to hold accountable the higher-ups and others who might have intervened. “There’s a recognition, which is new in the last few years,” Manly said, “that perpetrators don’t operate in a vacuum.”

For all the changes in public perception and accountability, the institutions that have faced shocking scandals in the past decade have not seen their reputations sink.

Timothy D. Easley, AP

John R. Thelin, a higher-education historian at the University of Kentucky, noticed as much in 2018 when he was flipping through channels looking for a Law and Order rerun. He happened upon a basketball game between Michigan State and the University of Louisville. Though he isn’t a regular fan of the sport, the two names piqued his interest, so he lingered to watch for a minute.

The arena was full. The fans were screaming. Thelin saw in them a visceral love and affection for their universities.

It was earlier that year that former Michigan State students and gymnasts had testified in horrific detail about their abuse by Nassar. There has been no serial sexual-abuse scandal at Louisville, but the university was then in the midst its own steady stream of controversy, including allegations that it had plied the basketball team with prostitutes and alcohol. University officials were not ultimately charged in the scandal, but the NCAA stripped the basketball program of its 2013 championship.

Thelin took in the scene. “It’s as if neither of these universities have suffered any remorse or penalty,” he said. “I don’t know what an appropriate penance would have been.”

[ad_2]

Source link