What’s Going On at Yale Law School? A Lot of Drama

[ad_1]

Yale Law School has found itself in the news a lot lately. That’s not so much because it was once again ranked as the No. 1 law school in the country, or because of a new program that will cover tuition for low-income students, or because it recently admitted the most diverse class in its nearly 200-year history.

Instead, it’s usually because something has gone horribly awry.

Case in point: Last month student protesters disrupted an event at the school. They were raucous, obnoxious even: Walls were banged on, slogans shouted, middle fingers extended. The ire of the 100 or so students was directed mostly at Kristen Waggoner, general counsel of the Alliance Defending Freedom, which bills itself as the largest legal organization devoted to “religious freedom, free speech, and the sanctity of life.” Scroll through ADF’s website, and you’ll see the group is opposed to gay marriage, abortion, and transgender women participating in women’s sports. The students were upset, too, with the Federalist Society for inviting Waggoner and also, apparently, with Kate Stith, a longtime Yale Law professor who moderated the event and who, at one point, told the protesters to “grow up,” an admonition that inspired further derision. (As it happens, the influential Federalist Society was born at Yale during a three-day symposium in 1982.)

In the weeks since then, the behavior of the protesters has been widely criticized. The former national-security adviser John Bolton, a Yale Law alum, called the students “intellectual brownshirts.” The governor of Tennessee put out a statement scolding the “student mob that violently disrupted” an event roughly 1,000 miles away from his state’s capital. A Yale alum wrote a column with the remarkable headline “Meet the Yalies Who’ll Be Kommandants of Your Children’s Concentration Camps.” Meanwhile, a federal appeals judge suggested that his colleagues “carefully consider” whether students who had protested should be “disqualified for potential clerkships.”

Not every take was quite that overheated.

Last fall Yale Law also made headlines when a student, Trent Colbert, sent a party invitation to members of the Native American Law Students Association in which he referred to the party’s location as a “Trap House” and informed recipients that Popeye’s chicken would be served. Some interpreted that as coded racism, and Colbert, who is part Cherokee, was strongly encouraged to apologize by Ellen M. Cosgrove, an associate dean, and Yaseen Eldik, the diversity director, who told him that his language in the email was “triggering” and “racialized.” In a ghostwritten draft apology, Colbert was supposed to say that he was sorry for the “trauma” he had caused and that he would “actively educate myself so I can do better.” Colbert refused to sign it, and instead published an essay about the “now-common ritual of compelled apology.”

And then there’s dinner-gate. Last April I wrote about the dubiously sourced allegations that Amy Chua, a Yale Law professor who needs no further introduction, was hosting drunken soirees at her house despite Covid-19 restrictions and possibly in violation of an agreement she’d made with the dean (though the nature of the agreement and pretty much everything else that supposedly happened is in dispute). That story was subsequently picked up by The New York Times, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, and New York magazine, which photographed Chua in front of her castle-like residence alongside her two impossibly fluffy white dogs.

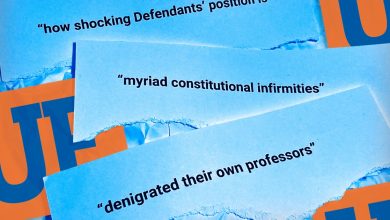

Silly as that all seemed, two students, Sierra Stubbs and Gavin Jackson, who had visited Chua’s house — though not, they say, to get wasted with federal judges — alleged they had been pressured to lie about what happened. When they refused, administrators “worked together in an attempt to blackball two students of color from job opportunities,” according to their legal complaint. They’re suing Yale and three administrators, including Cosgrove, Eldik, and Heather K. Gerken, the dean. Yale has issued a statement calling the suit “legally and factually baseless.”

Yale isn’t the only law school dealing with less-than-ideal publicity of late. Last month, at the University of California’s Hastings College of Law, protesters refused to let Ilya Shapiro, a senior lecturer at Georgetown University’s law school, speak at a Federalist Society event, shouting and pounding on desks until he had no choice but to leave. Shapiro tweeted in January that President Biden was choosing a “lesser black woman” as a Supreme Court nominee, a tweet he later deleted and for which he has apologized (Georgetown suspended him). In addition, I wrote recently about how student editors had resigned en masse from a journal published by Duke University’s law school in protest of an essay about the definition of the word “woman” that they considered transphobic.

Still, Yale’s law school has endured more brouhahas than most.

Some professors lay the blame at Gerken’s feet. “I have the sinking feeling that the values of the school are being eroded under this deanship,” one faculty member told me. Another said Gerken is a “genuinely nice person who doesn’t like telling people hard truths to their face.” The critics, who sought anonymity, basically accused the dean of repeatedly caving in to progressive students.

Gerken’s defenders were likewise reluctant to have their names printed. Several I spoke with argued that those taking shots at the dean are the law school’s old guard, and what they’re really upset about is Gerken’s emphasis on diversity and on punishing sexual harassment. One faculty member told me he thought the dean’s critics were setting a poor example for students.

The fact that no one will talk frankly on the record speaks to an overall loss of trust between certain factions of professors. More than one of them mentioned to me that they feared their comments in faculty meetings would be recorded and leaked. It mirrors the distrust between members of the Federalist Society and progressive students, with both sides complaining that they’re being recorded or photographed by their classmates in hopes the pictures or recordings will go viral and get them in trouble.

Gerken agreed to answer a few questions by email. She didn’t respond directly to her faculty critics but said her job is to “listen, to decide whether course corrections are needed, and to ensure that the institution stays true to its core mission.” She also affirmed her commitment to free speech on campus: “My first public statement as dean discussed the importance of free speech and engaging with different viewpoints,” she wrote.

Gerken did indeed discuss the importance of free speech in 2017, at the start of her deanship, pointing out that law schools hadn’t had to face “ugly free-speech incidents” and that might be because the education they provide “conditions you to know the difference between righteousness and self-righteousness.” She noted that while Charles Murray — the controversial scholar and co-author of The Bell Curve — had been shouted down on other campuses, he had spoken at the law school twice without interruption. “That’s exactly how a university is supposed to work,” she wrote.

That’s not how it worked last month. In a statement issued a couple of weeks after the Federalist Society incident, Gerken called the behavior of the protesters “unacceptable” and insisted that “at a minimum it violated the norms” of the law school. She stopped short of saying that the students had violated the university’s free-speech policy, and, at least so far, she has resisted calls to take disciplinary action. “Anyone who leads an institution at this moment knows that the issues we face today are complex and don’t lend themselves to easy answers,” she wrote in an email. “Because this is a storied institution, whenever we deal with the same, hard questions that other institutions are facing, we often find ourselves under a bright spotlight.”

[ad_2]

Source link