When a Scholar Is Accused of Being a Spy

[ad_1]

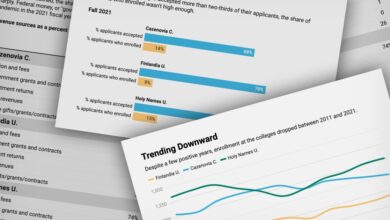

A little more than a week later, L. Rafael Reif, MIT’s president, released a statement pushing back against a core allegation in the criminal complaint against Chen, that he had personally pocketed nearly $20 million in payments from a Chinese university. No, Reif wrote, MIT had an agreement with Southern University of Science and Technology for joint research and educational activities, and the funds were paid to the institute. The charge was dropped from the official indictment.

In the months since, MIT has not commented on Chen’s case and declined to talk with The Chronicle about the investigation. But in Reif’s statement, he referred to Chen as a member of the MIT “family”; the university is paying the professor’s legal bills.

Reif and other top MIT administrators have also spoken out about the potential risks of the China Initiative to American innovation and about the danger of creating what Reif called a “toxic atmosphere of unfounded suspicion and fear” by appearing to single out researchers of Chinese descent for prosecution.

As Chen was being charged, some 900 miles to the south, another professor was preparing to go to court, the first trial of a researcher under the China Initiative. Like Chen, Anming Hu was Chinese-born and a professor of mechanical engineering, at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Like Chen, Hu was accused of hiding his Chinese affiliations when applying for federal grants.

MIT

That is where the similarities between the two cases end. University of Tennessee officials cooperated in a nearly two-year probe of Hu, handing over documents from his personnel file to federal investigators without a warrant or evidence of wrongdoing. They did not tell Hu he was under investigation. And at the behest of the FBI, the university approved a grant application from Hu to NASA, even though authorities had told administrators that he might have ties to the Chinese military. That led to his arrest: “How the FBI used UT to hunt for a spy,” said a headline in the Knoxville News Sentinel.

Following his indictment, Tennessee placed Hu on unpaid leave. The university later fired the professor, who is a naturalized Canadian citizen, when his work visa expired because of the charges against him.

Caitie McMekin, News Sentinel, Imagn

But Hu’s trial ended in a mistrial, and last month a federal judge acquitted him, saying prosecutors had failed to prove their case. “Even viewing all the evidence in the light most favorable to the government,” U.S. District Judge Thomas A. Varlan wrote in his decision, “no rational jury could conclude that defendant acted with a scheme to defraud NASA.”

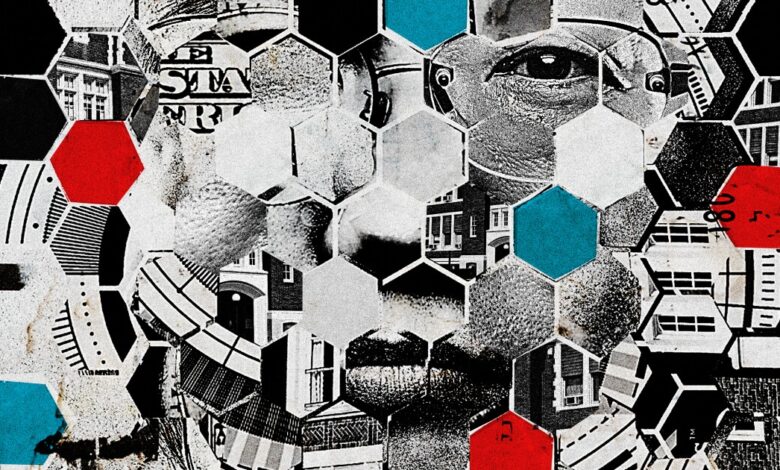

How could the two universities’ responses have been so divergent, with MIT supporting Chen and Tennessee essentially helping the FBI entrap Hu?

The answer is that universities, and the choices they make, don’t exist in a vacuum. How events played out at these two universities — a private, internationalized institution in the liberal Northeast and a public institution in a state with lawmakers who have been vocal about what they see as a threat from China — may say as much about where higher education sits along this country’s pervasive cultural divide as about the U.S.-Sino dynamic.

How could the two universities’ responses have been so divergent, with MIT supporting Chen and Tennessee essentially helping the FBI entrap Hu?

Both Tennessee and MIT are research-intensive universities, with large portfolios of government-funded projects. But although MIT takes in about four times the federal research and development funds as does Tennessee — close to half a billion dollars in 2019, according to the National Science Foundation — it attracts nearly as much research money from other outside sources, domestic and foreign. That makes it less dependent on the U.S. government for support.

Finances are only part of the picture. Private institutions must be responsive to their trustees, students, and alumni, while public universities like Tennessee answer to a far broader constituency, one that also includes elected officials, politically appointed governing boards, and, of course, taxpayers.

Those constituents are looking over the shoulder of public-college leaders, questioning, challenging, and at times opposing their decisions on issues such as affirmative action, campus speech, sexual assault, and even masking and vaccines. “I’ve been here 26 years,” said Mary McAlpin, a professor of French at Tennessee and president of the local chapter of the American Association of University Professors, “and it seems like everything now is politicized.”

Add China to the cacophony of criticisms of higher education. In Washington, and in some state capitals, lawmakers have condemned colleges’ work in China as counter to American interests. Tennessee’s senior U.S. senator, Marsha Blackburn, has proposed legislation that would prevent Chinese nationals from working on federally funded STEM research and ban Chinese graduate students in those fields.

Lincoln Agnew for The Chronicle

College administrators may be reluctant to cross elected officials — in both political parties — who are sounding red alerts about Communist China, said Brendan Cantwell, a professor at Michigan State University who studies both American higher-ed policy and international education. “For a place like the University of Tennessee, it’s a land mine.”

Hu’s lawyer later argued that the professor had not reported the appointment on conflict-of-interest forms because his compensation was so low it didn’t trigger Tennessee’s disclosure requirements. And he had listed the Beijing position on other university documents, including in his tenure package, A. Philip Lomonaco, the defense lawyer, noted.

When the FBI interviewed Hu, he denied any wrongdoing and pointed to the benefits of his research — he is an expert in brazing, a sophisticated welding technique — to NASA. When the agent asked Hu to report back to him about “security concerns” on a trip he was to take to China — in other words, to spy for him, Lomonaco said — the professor called his travels off.

Lacking evidence, the FBI put Hu and his son, then a college freshman, under surveillance. They also approached the University of Tennessee for help.

During Hu’s trial, administrators testified that agents shared PowerPoint slides that alleged Hu had ties to the Chinese military. The university cooperated with the FBI, sharing documents from the professor’s personnel files with the FBI, including conflict-of-interest forms, grant paperwork, and emails, without a subpoena and without alerting Hu.

In an interview with The Chronicle, John Zomchick, Tennessee’s provost, said that the state’s comprehensive open-records law means few documents at the public institution are shielded from disclosure. He also said that universities can be required to share files with federal granting agencies. However, Zomchick, who was vice provost for faculty affairs at the time of the Hu investigation, said Tennessee is reviewing its disclosure policies to require subpoenas for certain sensitive paperwork, such as performance evaluations, and plans to inform faculty members when they are the subject of a records request. “That’s one of our takeaways,” Zomchick said.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Tennessee’s participation in the investigation centers on its actions when Hu applied for a new NASA grant partway through the FBI probe. At the trial, Jean Mercer, associate vice chancellor for research, testified that she had reservations about signing off on the contract. “I was concerned for the university and concerned for the faculty member,” she said after Lomonaco asked her if she was worried that doing so would “cause Professor Hu to step further down the line of committing fraud.”

Mercer turned to the university’s general counsel for guidance, she testified. The lawyers advised her to go ahead. The grant, which Hu won, was part of the indictment against him, in which he was charged with three counts of wire fraud and three counts of making false statements.

When asked why administrators had approved the grant, Zomchick said that “because there was no evidence one way or another, we decided it was not appropriate for us to interfere with [Hu’s] research or work.”

The short-term calculus that led officials to cooperate could have lasting repercussions, Gross fears. “This doesn’t look good for the university when it looks like we’re complicit in racial profiling by cooperating with the FBI.”

This doesn’t look good for the university when it looks like we’re complicit in racial profiling by cooperating with the FBI.

Jenny J. Lee, a professor of educational policy and practice at the University of Arizona, has been studying the China Initiative’s impact on scientists of Chinese descent. The University of Tennessee is not alone in fearing reputational damage from faculty members who appear to have hidden ties to China, she said — in fact, colleges want to avoid the kind of headlines the Hu case generated. “They don’t want things to get to press,” Lee said. “They want to handle things quietly.”

As a result, universities cooperate with authorities and may even proactively seek to impose institutional sanctions, such as fines or reassigning some duties. Lee said she knows of a faculty member at a public university in the West who was removed from a federal grant, had his research role taken away, and saw his doctoral students reassigned. So far, there are no charges or public complaints against him.

At Tennessee, Zomchick said the university felt an obligation when federal officials, including grant-making agencies, raised concerns about Hu. “We’re a public university. We have responsibilities to our granting agencies, to our taxpayers to make sure that we are upholding our fiduciary expectations and duties,” he said.

Colleges can ill afford to jeopardize such funding. The U.S. government is the single largest source of support for university research, accounting for 53 percent of all spending, although that share has declined in recent years.

Yasheng Huang, president of the Asian American Scholar Forum, a group that advocates for faculty members of Asian descent, worries that colleges’ reliance on federal funds could shape their behavior. He fears that universities might discourage work with China because “they don’t want to be cut off by NIH or NSF.”

Huang teaches at MIT — he is an economist, not a scientist — which gets more federal research funds than all but a handful of other universities. But it also pulls in millions of dollars a year from foreign governments and international businesses.

Few colleges are as internationalized as MIT, which has an extensive network of research and educational partnerships around the globe. It has helped start universities in Abu Dhabi, Russia, and Singapore. More than 40 percent of its graduate students come from abroad.

That creates a different dynamic. For MIT, the appearance of pulling back on international collaboration could be an enormous reputational risk.

In Tennessee, the second largest outside source of research support is the state; the Knoxville campus got about $14 million in state- and local-government research funds in 2019.

In fact, Tennessee has done comparatively well in financing its public colleges, with per-student expenditures slightly ahead of national rates. The state pays for two years of community-college tuition for all high-school graduates.

However, faculty members said that support comes with strings attached, with pressure for colleges to be on the right side of issues such as campus speech, sex education, and critical race theory. In 2016, legislators stripped funding for the university’s office of diversity after a memo on gender-neutral pronouns and more-inclusive holiday celebrations became Fox News clickbait. A previous chancellor lasted barely a year before she was ousted after run-ins with lawmakers.

“State legislators have been extremely vocal about the university,” Gross, the Faculty Senate president, said. Given what he called “anti-intellectual attitudes” in the statehouse, university administrators may have felt that pushing back on the investigation of Hu would have invited unwanted criticism.

When asked if he felt political pressure from elected officials in the Hu case, Zomchick replied, “Categorically none,” adding he wasn’t even sure if lawmakers were aware of the investigation.

Stefani Reynolds, Getty Images

But concerns about Chinese influence on American campuses were on the minds of public officials in Washington and in Nashville, the state capital. Blackburn, one of Tennessee’s U.S. senators, has introduced several bills focused on higher ed’s China ties, including measures to bar American professors from taking part in Chinese talent-recruitment programs. Last year, a tweet of hers went viral: “China has a 5,000 year history of cheating and stealing. Some things will never change…”

When Hu was arrested, Blackburn again took to Twitter. “China’s soft power approach to infiltrating and spying on our universities is alarming, which is why we need to continue to support efforts to root out these bad actors,” she wrote.

In March, as Hu’s case was heading for trial, Gov. Bill Lee, a Republican, introduced legislation barring Confucius Institutes, controversial Chinese-government-funded language and cultural centers, from Tennessee campuses and requiring colleges to report any gift or contract from a foreign source of $10,000 or more. Although he did not mention Hu’s case, Lee called the measure a “key priority,” citing his concern that universities had become a “a place for foreign governments to operate in the shadows.”

Little more than a month later, lawmakers approved the bill. In the state Senate, there was a single dissenting vote. In the House, it passed unanimously.

“There is no single entity that exercises a more pervasive nefarious influence across a wide range of American industries and institutions than the Communist Party of China,” Gov. Ron DeSantis said at a signing ceremony in June. “Academia is permeated with its influence.”

As in Tennessee, legislative action follows China Initiative cases. Researchers at the Universities of Florida and Central Florida and at a state-funded cancer institute have resigned or were fired because of undisclosed foreign ties. Still, some faculty members think elected officials are using the issue to score political points. “I think Gov. DeSantis sees himself as Trump’s successor, and Trump has been on an anti-China kick,” said Thomas A. Breslin, a professor of politics and international relations at Florida International University, who studies both U.S. and Chinese foreign relations.

I think Gov. DeSantis sees himself as Trump’s successor, and Trump has been on an anti-China kick.

Among the American public, negative views of China are at an all-time high, with nearly three-quarters of Americans in a recent Pew Research Center survey holding an unfavorable opinion of China.

That skepticism extends to China’s presence on American campuses. A majority of Americans favor visa restrictions on Chinese students. Half of those polled by the American Council on Education earlier this year believed efforts by the Chinese government to pay American scientists for research through “illicit or secret agreements” is “widespread problem.”

Paul Ortiz, a professor of history at the University of Florida, said there is a “crisis” of anti-Asian racism in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, but he also sees the foreign-influence bill as part and parcel of a broader trend toward political interference in the state’s colleges. As in Tennessee, elected officials have sought to tighten their grip on public colleges, around issues like ”viewpoint diversity” and, more recently, mask and vaccine mandates.

Politicians have exploited the cultural and partisan divides around higher education, Ortiz, who is president of the university’s chapter of the United Faculty of Florida, said, and the attacks on Chinese ties are no different. “They revert to anti-Chinese scapegoating and attacking the pointy-heads in higher ed,” he said. “This is part of the culture wars.”

David P. Norton, the vice president for research at the University of Florida, said he would have preferred a more risk-based approach, rather than singling out entire countries for scrutiny, regardless of the nature of the ties. Still, complying with the new mandate may be made easier by the fact that the university substantially revamped its research-reporting system since the 2019 cases of disclosure failures.

MIT, too, may have had the perverse advantage of an early controversy — in 2018, following the killing of the dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the university came under criticism for taking more than $7 million a year in sponsored research from Saudi Arabia. It has put in place a thorough and considered process for vetting and disclosure of faculty international engagement, in which a high-level advisory committee reviews international projects for security risk, economic risk, and political and human-rights risk.

If Florida and MIT had a head start, Tennessee is now taking a hard look at its own system for assessing potential conflicts. Zomchick, the provost, said the new disclosure process will rely heavily on department chairs, who he said are in the best position to know and understand professors’ international-research ties. There also will be a “multifaceted” educational campaign to ensure faculty members understand what they need to report.

In addition, Zomchick plans “listening sessions” to hear from Asian and Asian American faculty members. “I want to hear their concerns, I want to address their concerns, and I want to work hard to rebuild trust,” he said. The sessions need to happen “ASAP,” he added.

Might students and scholars steer clear of states like Florida where international collaboration has come under the legislative microscope?

Zomchick may be right about the urgency. Lee, the University of Arizona professor, has been working with the Committee of 100, an organization of prominent Chinese Americans, to survey scientists about the impact of the China Initiative. Researchers of Chinese descent are far more likely than other scientists to report feeling targeted by the government and that they are increasingly hesitant to engage in international collaboration, according to Lee’s preliminary findings.

The China Initiative could make it more difficult for American universities to recruit and retain Chinese and Chinese American professors and graduate students. Or, given the differences in institutional responses, it could make it more difficult for some colleges: Could universities that are perceived to have stood up more forcefully on behalf of their researchers be more attractive to Asian and Asian American applicants? Likewise, might students and scholars steer clear of states like Florida where international collaboration has come under the legislative microscope?

“Scientists are highly mobile,” Lee said, noting that she has known professors who have moved from red to blue states.

An exodus of Chinese researchers and grad students, whether from certain institutions or the United States as a whole, could crush certain disciplines, like physics, where more than a quarter of all doctorates awarded annually by American universities go to Chinese nationals.

“Try to run a Ph.D. program if you don’t have students from China — you can’t fill your classes, you can’t run your lab,” Brad Farnsworth, a higher-education consultant and former vice president for global engagement at the American Council on Education, said. “This is your bread and butter. This is the future of your discipline.”

Beauvais Lyons, chair of the Faculty Affairs Committee at the University of Tennessee, worries that what he sees as in-the-moment administrative damage control in the Hu case could have long-term fallout for his institution. “Reputations,” said Lyons, a professor of art, “are a lot easier to tear down than to build up.”

Try to run a Ph.D. program if you don’t have students from China — you can’t fill your classes, you can’t run your lab.

Lyons and his Faculty Senate colleagues have been pressing Tennessee leaders for answers in Hu’s case and for changes that would better protect other professors in the future. The day after his acquittal, the university offered Hu his job back, along with some back pay and funds to restart his research. In an October 18 letter to Zomchick provided to The Chronicle by the university, Hu said he was “deeply appreciative” of the offer of reinstatement but asked administrators for assistance in getting a new work visa, including requesting that Tennessee’s congressional delegation help expedite its approval.

With much still unresolved about colleges’ responses and responsibilities in the China Initiative, some faculty members are stepping forward. In September, 177 professors at Stanford University sent a letter to Attorney General Merrick B. Garland, calling on him to shut down the federal investigation. Since then, faculty members at Princeton, Temple, and the University of California at Berkeley have sent their own letters, and the APA Justice Task Force, which advocates for Asian American scientists, is seeking professors from other institutions to sign on.

Steven Kivelson, a professor of physics, co-authored the Stanford letter. He’s been disappointed that more university leaders haven’t spoken out against the China Initiative, and with many students and colleagues from China, he said he could no longer be silent.

“I kept telling friends that they really had nothing to worry about, that the United States is still a welcoming country and a country of laws,” Kivelson said, “but it became harder for me to do that with complete assurance.”

.

[ad_2]

Source link