Why Some Colleges Publicly Punish Student Groups

[ad_1]

Jeffery Stefancic and his colleagues in Purdue University’s Office of Student Rights and Responsibilities had become accustomed to the calls from worried parents.

“‘My son or daughter wants to join this organization; are you aware of anything going on?’” he said they’d ask. The parents wanted to know whether student groups, often fraternities and sororities, were in good standing with the university — an understandable concern considering decades of news headlines on some of the organizations’ rampant hazing and other misconduct.

So about a decade ago, Stefancic, an associate dean of students in Purdue’s students’ rights office, decided to publish student organizations’ disciplinary statuses so that students and their families could make informed decisions about joining the groups.

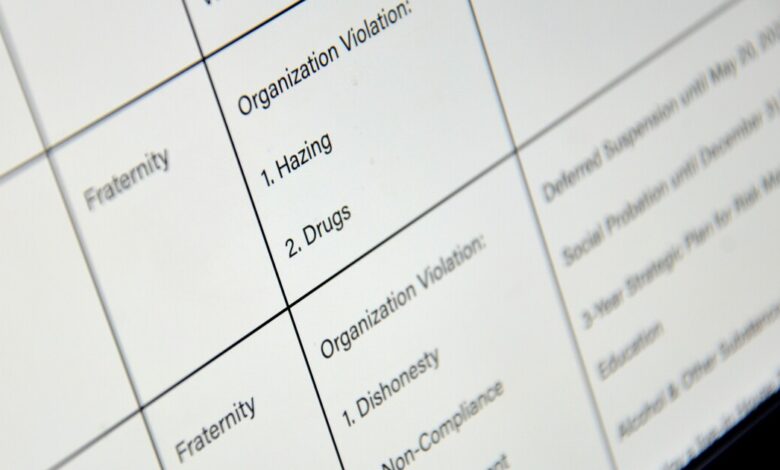

A dedicated page on Purdue’s website features a report of all the student organizations that currently face sanctions and a longer list of organizations that have faced discipline in the last two years. The entries include the sanctions facing each organization and the offenses that got it on this website in the first place. One fraternity chapter, for example, is suspended until the fall of 2024 for endangerment, dishonesty, and alcohol violations, among others.

Student-conduct professionals say more campuses are adopting these public-facing reports amid a push for greater accountability among student organizations that misbehave. Some say the reports can help inform students, parents, and others of red flags raised in the past, and may deter misconduct, although there’s a lack of research to support that idea. Others worry this public naming and shaming could unintentionally encourage dangerous behavior.

Christina Parle, president-elect of the Association for Student Conduct Administration and the co-founder of the diversity, equity, and inclusion consulting firm Social Responsibility Speaks, said it is difficult to quantify how many colleges publish organizational-conduct reports because the lists vary so greatly from institution to institution.

People should be able to enter into an organization being informed.

But, she said, “It’s become somewhat of an industry standard for a lot of campuses,” as new hazing laws require colleges in some states to disperse conduct information.

Texas, for example, requires that each public college prominently display on its website “a report on hazing committed on or off campus” by a recognized organization. The report must include information on each hazing count and the disciplinary actions taken against the offending organization. Texas’ anti-hazing law was amended to include the requirement in 2019, after the hazing-related death of a student at the University of Texas at Austin.

A similar law went into effect in Washington in July, championed by the parents of a Washington State University student who died in a fraternity-hazing incident three years ago.

Beyond Fraternities and Sororities

Adam McCready, an assistant professor in residence in the University of Connecticut’s Neag School of Education and the editor of Oracle, a research journal for fraternity and sorority advisers, said that student-conduct offices’ efforts to list organizations’ misconduct was born out of efforts by fraternity-and-sorority-life offices to be more transparent about Greek-letter organizations’ conduct after hazing-related deaths.

Some colleges, like Indiana State University, limit the conduct trackers to only Greek-letter organizations and post the lists on their Greek-life websites.

Craig Enyeart, assistant dean of students and student-conduct director at Indiana State, explained that the Greek-life office maintains a “score card” that tracks chapters’ delinquent behavior, as well as their awards and average member GPA.

“Indiana doesn’t have a current law that says we have to maintain a score card,” Enyeart said. “But a lot of institutions feel that if you’re going to join an organization, and we know that there have been issues in the past, … people should be able to enter into an organization being informed.”

Enyeart said it doesn’t make sense for the student-conduct office to track delinquent organizations on its website, because the office tries to stay neutral. If it reported only organizations’ conduct violations, and not their accolades and philanthropic efforts, that wouldn’t be neutral, he said. “There’s more of a story to an organization than just the misconduct.”

But the student-conduct office is not in the business of feting organizations for good deeds, either — and that’s why the Greek-life office handles it.

Purdue’s disciplinary-status report doesn’t list organizations’ awards and GPAs, but Stefancic said the list is neutral because fraternities, club sports, and academic organizations are all equally subject to being named for conduct violations. Purdue’s report logs expired sanctions against the Arnold Air Society, the Marwood Cooperative House, and the South Asian Student Alliance, in addition to a number of fraternities and sororities.

Indiana State and Purdue are participants in the National Fraternity and Sorority Scorecard, a longitudinal research project run by Pennsylvania State University’s Timothy J. Piazza Center for Fraternity and Sorority Research and Reform. (The center is named for a student who died after a hazing incident in 2017.) The project aims to create “a national picture of the state of fraternities and sororities across the country” by aggregating members’ grade-point averages, philanthropic contributions, service hours, and organizational conduct.

Stevan Veldkamp, director of the Piazza Center, said about 95 to 100 campuses provide score-card data, up from 75 when the project started three years ago.

In Virginia, Veldkamp said, a new law against hazing requires colleges to report their conduct statistics to the Piazza Center, prompted by the hazing-related death of a Virginia Commonwealth University student in 2021.

“More institutions are creating some type of sunlight on their conduct statistics,” Veldkamp said.

To Shame or Not to Shame?

Student-conduct professionals say the reports are an important transparency measure that can help build trust in an institution.

“You don’t buy a new car or a house without having some background information,” McCready, of the University of Connecticut, said. “And you don’t take a student to college without having some background information.”

The benefits of openness are not just external, McCready said. Organizations may feel less fearful of their institutions if they realize that there are other, less severe punishments besides getting kicked off campus.

Colleges might take up disciplinary-status lists as a deterrent to hazing or other dangerous behaviors. Some colleges hope that the fear of being on the list encourages a group to clean up its act, McCready said.

But McCready and other experts said they believed that the deterrent effect isn’t very strong.

“An organization or individuals in an organization are not really thinking, ‘Oh, we shouldn’t do this, so we don’t end up on that list,’” McCready explained. “I think more the mentality is, ‘Oh, we’re never going to get caught for this.’”

At Purdue, the goal of publishing the list was more openness than it was deterrence, Stefancic said.

“You’re bringing in folks to your group,” he said. “You want them to make good decisions about whether or not they should get involved. And part of that is not only the good stuff about your organization, but is there any sort of bad stuff that they should be aware of?”

The lists do raise some concerns that may dissuade colleges from publishing them. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act protects the privacy of certain educational records for students; even though the federal law doesn’t apply to student organizations the same way it applies to individuals, colleges may be afraid of violating Ferpa if group rosters are easily available, Parle said. Indiana State’s fraternity and sorority life score card, for example, withholds several chapters’ grade-point averages because they have so few members.

“If I can easily find that Christina Parle is in XYZ student organization, I could see why it may concern some people,” Parle said.

Another concern is that students who seek out opportunities to haze or gain access to hard drugs can use the lists to find groups that embrace dangerous behavior. But those students are probably “few and far between,” McCready said.

McCready, Veldkamp, and Parle said they were not aware of any research about how effective disciplinary-status lists are at deterring bad behavior or building trust with students.

One concern is that students who seek access to hard drugs can use the lists to find groups that embrace dangerous behavior.

Pietro Sasso, a graduate faculty member in educational leadership at Stephen F. Austin State University, in Texas, said anti-hazing laws that require colleges to report conduct violations are too new for any conclusions to be drawn about efficacy. But research on the Clery Act, which requires colleges to disclose crime data, has found that the mandated reporting does not influence student decision-making or enrollment.

“We know from 20 years of research about mandated campus reporting that it unfortunately does not influence student decision making, but only allows students to feel that their campus is much safer,” Sasso said in an email.

Veldkamp said the Piazza Center is working on a multi-institutional research study to understand what kind of difference conduct reporting makes.

“There’s an opportunity here for doctoral students or other scholars to address this and see what are some effective means to change organizational behavior,” McCready said.

[ad_2]

Source link