As Colleges Focus on Quality in Online Learning, Advocates Ask: What About In-Person Courses?

[ad_1]

As colleges’ online catalogs grow, so too has the push to develop standards of quality for those courses. But are in-person classes getting the same attention?

If you ask many online-education advocates, the answer is “no.” And the solution, many say, is for colleges to adopt standards and policies that set consistent expectations for quality across all courses, whether they’re remote or in a classroom.

While decades of research and the pandemic-spurred expansion of online learning have helped demystify it, and build confidence in its efficacy, these advocates say the misconception lingers that remote education is inherently lower in quality than instruction in the classroom. And that stigma, they say, puts a magnifying glass to online ed, while largely leaving in-person classes to business as usual.

“To think through all of our college experiences, we have all been in large lecture classes” with minimal to no contact with a professor, said Julie Uranis, senior vice president for online and strategic initiatives at the University Professional and Continuing Education Association. In other words, an in-person class doesn’t necessarily guarantee more student engagement and instructor support. “But for some reason, that bar is higher for online.“

Some college administrators can attest to this. When accreditors ask institutions to prove that all of their courses are equally rigorous, colleges’ interpretation of that instruction has often been to “show that online courses are up to the standard of” in-person courses, “not the other way around,” wrote Beth Ingram, executive vice president and provost of Northern Illinois University, in an email.

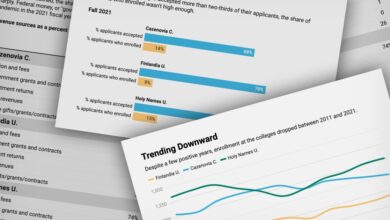

The discrepancy seems to be borne out in the data, too. A reported 38 percent of in-person courses have no quality-assurance standards to meet, according to a survey of more than 300 chief online officers by Quality Matters, an organization that helps ensure quality in online education. That compares with 17 percent of online synchronous courses and 5 percent of online asynchronous courses.

To be sure, online and in-person aren’t wholly interchangeable — there are nuances to account for. Distance education, for example, is governed by federal regulations that require courses to include “regular and substantive” interactions; that necessitates course design that intentionally creates opportunities for students to engage with one another and their professor. Online incorporates more technology, too, which means additional checks for security measures, proper integration — are the links and embeds all working? — and accessibility features.

Caveats aside, though, online-education advocates like Bethany Simunich, vice president for innovation and research at Quality Matters, say higher ed needs to stop “othering” and setting different bars for different modes of learning. Especially as the lines between them blur together. (A lot of in-person courses, for example, are now “web enhanced,” with faculty members using the campus learning-management system. And many colleges now offer hybrid courses with both in-person and online components.)

The focus instead, Simunich said, should be on a big-picture question: Is this a high-quality learning experience for students?

Numerous institutions are working to keep that question front and center. Oregon State University crafted a universal quality framework. North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University adopted a common syllabus template. Montgomery College, in Maryland, requires learning-management-system training for all new faculty members teaching credit-bearing courses. Harford Community College, also in Maryland, has revamped its faculty-observation forms.

“Online and face-to-face are very different things. But it doesn’t mean systems have to be separate,” said Jeff Ball, director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Harford. “We’re learning that we need to talk about them together in very conscious ways.”

Setting a Standard

It’s not uncommon for faculty members to teach an array of courses: some online, some in-person, some a hybrid blend. Oregon State University is no exception.

That’s why it made sense to develop an “umbrella” quality-teaching framework that outlines standards the institution expects from any of its courses, said Karen Watté, director of course-development and training at Oregon State’s Ecampus. It would, in her words, “elevate teaching across the board.”

That framework, completed in 2021, includes expectations like:

- Providing materials in formats that are accessible by all learners, including curricular materials designed with recommended fonts and colors.

- Fostering community outside of the classroom.

- Measuring, documenting, and using achievement data to inform instruction.

Around that same time, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University adopted another tool: A universal template for course syllabi to create a cohesive student experience across classes, said Tonya Amankwatia, assistant vice provost for distance education and extended learning.

This newer template has introduced standards that weren’t previously required in faculty syllabi. For example, it includes a communications policy stating that faculty “must notify students of the approximate time and method they can expect to receive an answer to all communications,” with the expected window being 48 hours, apart from holidays. The syllabus template also links to a “common policies” document that directs students to resources such as minimum technology requirements.

What was particularly exciting, Amankwatia said, was that the template wasn’t the result of a top-down mandate. Faculty members teaching both online and in-person courses had, in fact, led the charge. “It was one big visible move that no senior administrator had to say” or ask for, she said.

Prioritizing Professional Development

The success of any course, experts say, also comes down to investing in professional development.

For Montgomery College, in Rockville, Md., that has meant doubling down on its “Digital Fundamentals for Teaching and Learning” training, which teaches faculty members how to take advantage of the campus’s learning-management system. (All credit-bearing classes at Montgomery are required to have a course page in the LMS).

The training, which takes about 20 hours to complete, starts with foundational skills — how to post files and upload a syllabus — and builds from there: How to create and manage discussion boards. How to embed videos, and caption them to support accessibility. How to set up an online gradebook for students to track their performance.

The college first rolled out this training in the early days of the pandemic to ease the pivot to fully remote learning. About 70 percent of full- and part-time faculty members teaching credit-bearing courses completed it in 2020. It was so useful that the college has since required each new faculty member who teaches for credit to take the training, whether they’re teaching online, in-person, or both, said Michael Mills, vice president of the Office of E-Learning, Innovation, and Teaching Excellence.

Montgomery also offers a voluntary quality-assurance microcredential — a series of three badges a faculty member can earn outside of work hours that, among other things, indicates knowledge of “inclusive quality course design and delivery.”

Mills acknowledged that the college doesn’t offer a pay incentive to complete that microcredential. “The incentive is a better course design,” he said. “For some faculty, that’s important to them.” He noted that it may help part-time faculty secure additional teaching opportunities at other institutions.

Revisiting Observations

Setting standards is one thing. Evaluating courses based on those standards is another; policies can be tricky to put in place and enforce broadly. (It’s an area where online education still struggles, too.)

That also goes for faculty evaluations. That process is often codified in collective-bargaining agreements, and grants faculty members a high degree of autonomy in teaching.

At Harford Community College, in Bel Air, Md., “observing” a faculty member’s course is one part of the larger annual evaluation process. And a goal for that piece, at least, is consistency where it makes sense.

The college’s refreshed faculty-observation forms for both online and in-person teaching — the online one is still in draft mode — are similarly formatted. Both have done away with numeric values and rating scales. Both set parameters around what the observer is seeing, and when they’re seeing it (for in-person, it’s a single class. For online, it’s access to an agreed-upon portion of the course for an agreed-upon time frame). Both check to see if the instructor has fostered “an engaging learning environment.”

But there are differences. In the online-course observation form, for example, the reviewer is asked to check to see that links and “technical aspects of the course are in working order,” and whether navigation is “user friendly.” In the in-person observation, the reviewer is asked about the pace: Was the instructor teaching at a speed that allowed students to process the content?

“It’s like a Venn diagram,” said Elizabeth Mosser Knight, associate dean for academic operations at Harford. “There’s the overlap, but then there’s the nuance, because they’re unique in some ways.”

It’s these types of conversations that get online advocates like Simunich excited about the potential for progress.

“As these conversations are all starting to merge and come to a head, institutions are going to have to make a choice,” she said, “about whether they’re going to publicly address and talk about quality.”

[ad_2]

Source link