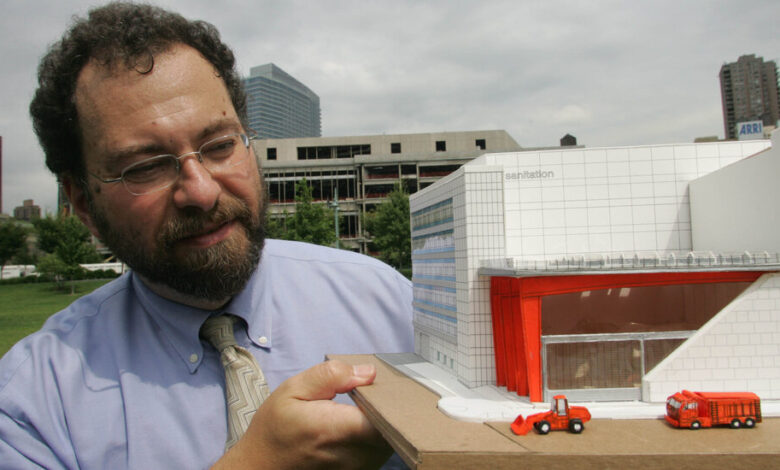

Michael Friedlander, Urban Architect of Offbeat Designs, Dies at 63

[ad_1]

In the 1970s, Michael Friedlander was an architecture student at the Cooper Union, his head bursting with bodacious, unconventional designs. Upon graduating, he settled for a stopgap job with the City of New York, which included more prosaic assignments like drafting blueprints to renovate locker rooms for sanitation workers.

Over his 40-year career with the Sanitation Department — he was an in-house architect, a manager of various projects and finally director of special projects — Mr. Friedlander never gave up on his crusade to transform the public’s view of civic architecture from intrusive mediocrity to something worthy of approval, or even veneration.

His vision was ultimately epitomized in the form of a sculptural Sanitation Department salt-storage shed on the fringe of TriBeCa. The glacially blue concrete crystalline cubelike structure, 69 feet high, is called the Spring Street Salt Shed and appears, with a little imagination, to form a coarse grain of salt.

Mr. Friedlander described the $20 million structure as a whimsical “architectural folly” that can hold 5,000 tons of salt.

A community coalition that included the actors Casey Affleck, Kirsten Dunst, James Gandolfini and John Slattery and the musician Lou Reed opposed the shed and the adjacent garbage-truck garage. But as the architecture critic Michael Kimmelman wrote in The New York Times in 2015: “Opponents of the sanitation project in Hudson Square may not have gotten exactly what they wanted. But they were fortunate. They got something better.”

Mr. Kimmelman added, “I can’t think of a better public sculpture to land in New York than the shed.”

Mr. Friedlander died on March 21 in a hospital in Manhattan. He was 63.

His niece Julia Friedlander said the cause was complications of an infection.

Born into a Jewish household, Mr. Friedlander became a practitioner of Nichiren Buddhism, whose principles, particularly those of environmentalism and sustainability, he tried to apply to his work.

Asked by a community board member to explain why the truck garage he designed at 12th Avenue and West 55th Street was punctuated by so many windows, Mr. Friedlander replied, unpretentiously, “There are people inside.”

That garage won an award in 2007 from the city’s Art Commission (now the Public Design Commission). So did a shed with translucent tent fabric in Far Rockaway, Queens, that is used to store ice-melting salt for sanitation trucks to spew on winter roadways. He also received a lifetime achievement award from the commission.

But Mr. Friedlander is probably best known for overseeing the design and construction of the Spring Street Salt Shed, at West and Spring Streets near the Hudson River, as well as the adjacent garage. Those structures won an Honor Award from the 2018 American Institute of Architects.

Tobi Bergman, the chair of Community Board 2, which had initially opposed the project, told Architect magazine in 2016: “Anybody who has seen it has to be happy with it. It’s a real example of how these things can be done well.”

Mr. Friedlander told The Times in 2015 that his secret to overcoming not-in-my-backyard opposition to public works was straightforward: “Build the best building in the neighborhood.”

“I keep learning from one building to the other,” he said. “I may not make a ton of money, but I’m having fun.”

Michael Jay Friedlander was born on June 6, 1957, in Manhattan to Frances (Kempner) Friedlander, a teacher, and Joseph Friedlander, an insurance representative.

Growing up in an East Village tenement, he began thinking about urban design early. “In kindergarten,” he told The Times, “I was building housing developments with highways between them.”

After graduating from Seward Park High School in Manhattan, he earned a degree in architecture from the Cooper Union in 1979.

In 2005 he married Jeanette Emmarco, who later became a staff analyst with the Parks Department and the Human Resources Administration. She survives him, along with his brothers, Jeffrey, Bruce and Kenneth. Jeffrey Friedlander retired as second in command in the city’s Law Department in 2015.

The salt shed had many mothers and fathers, starting with the architects who collaborated on the project, WXY and Dattner Architects; Amanda M. Burden, who chaired the City Planning Commission under Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg; and James S. Polshek, a member of the Public Design Commission.

Rick Bell, executive director of the excellence program in the city’s Department of Design and Construction, said in 2015 that the shed might be the most important change to the public face of the Sanitation Department since its fleet was painted white in 1967.

The shed’s concrete walls are six feet thick, leading the architect Richard Dattner to imagine some future civilization stumbling upon it just as Charlton Heston’s character discovers the remnants of the Statue of Liberty in the film “Planet of the Apes.”

“They will wonder,” Mr. Friedlander said, “why did these people worship salt?”

[ad_2]

Source link