The Hidden Dangers of Yo-Yo Dieting and How It Affects Your Body

[ad_1]

Throughout 2021, Good Housekeeping will be exploring how we think about weight, the way we eat, and how we try to control or change our bodies in our quest to be happier and healthier. While GH also publishes weight loss content and endeavors to do so in a responsible, science-backed way, we think it’s important to present a broad perspective that allows for a fuller understanding of the complex thinking about health and body weight. Our goal here is not to tell you how to think, eat, or live — nor is to to pass judgment on how you choose to nourish your body — but rather to start a conversation about diet culture, its impact, and how we might challenge the messages we are given about what makes us attractive, successful and healthy.

When Carol Perlman was in fourth grade, she eagerly joined a school-sponsored group called the No-Thank-Yous. “It was for kids who wanted to lose weight — how sad is that?” says the 48-year-old psychologist in Massachusetts, who looks back at the club she joined when she was nine as the starting point of four decades of on-and-off dieting. “I’ve hopped from one diet to another, including South Beach, Beach Body and Weight Watchers about a bazillion times,” she says. “Each time I lose about 10 pounds, but then as soon as I start eating normally, it comes right back. It takes an incredible amount of work to lose the weight, and it when I gain it back, it’s so discouraging — it feels like I’m moving backward.”

Sound familiar? Perlman — who falls well within what the Centers for Disease Control labels a “normal BMI” — is just one of the estimated 55% of American women and 34% of men who lose weight and then gain it back over and over again, a phenomenon known as yo-yo dieting, or weight cycling.

That kind of up-and-down may seem so normal to so many of us that it’s not even worth discussing — who hasn’t dropped a few pounds before a class reunion or beach vacation, only to gain it back as soon as the event is history? But is showing us that chronic weight cycling, especially if you start dieting as young as Perlman did, may be doing long-term damage to our bodies, not to mention our mental health.

This content is imported from {embed-name}. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

The psychological toll of weight cycling

While losing weight by following a restrictive diet may not be difficult at first, keeping that weight off is often nearly impossible as your body reacts to what it suspects is a famine scenario by slowing down your metabolism and sending hunger signals to your brain.

This means the majority of dieters gain the weight back — often adding on a few additional pounds in the process. This leads to a cycle of emotional highs and lows, first feeling great about yourself, then feeling like a failure, says Mary Pritchard, Ph.D., professor of psychology at Boise State University, who researches body image and dieting.

The very fact that you’ve lost weight in the past can make you feel more pressure to lose it the next time. “We think, well, I’ve done it before, why can’t I do it again? — even if that may not be realistic for your body,” says Pritchard, who is currently studying this phenomenon in postpartum women, who can feel intense pressure to “snap back” after giving birth.

Pritchard also points out that social media has raised the stakes even higher, as we excitedly post photos of ourselves at our lowest weights — and then have them there forever to remind us of how we “failed” when we regain the weight. “Expecting yourself to have a 20-year-old body at age 45 is unrealistic for most people — in addition to the changes in metabolism and the loss in muscle mass as we get older, hormonal shifts caused by pregnancy, perimenopause, and menopause make weight loss more difficult,” Pritchard points out.

Perlman agrees that the guilt comes from inside and out. “When you’ve been at a certain body weight, it’s hard to give up the idea that you can still get back there,” she says. “Also, you see other people who are thin, and think, Why can’t I be like them?”

With this constant merry-go-round of emotions, it should come as no surprise that a large 2020 study in the journal PLOS One found that the more times a person has weight-cycled, the greater their risk for symptoms of depression, which held true for both men and women. The researchers theorize that “internal weight stigma” — that inside voice shaming you each time you gain weight — is the mediating force.

To be clear, weight cycling is not just an issue with adults who are trying to lose a significant amount of weight. According to the it is increasingly common with younger women — even girls as young as five — who are unhappy with the way they look (the study mentions the usual suspects of magazine images, Barbie dolls and trying to achieve a specific type of body to make a sports team as some of the motivating factors for girls to try to lose weight). Perlman recalls that when she first started dieting at nine, it was because she felt the clothes that were popular at that time were not flattering on her body.

Not only is it incredibly disheartening to think about grade-school girls trying to count calories and carbs, but the younger you are when you hop on the dieting merry-go-round, the more opportunities you have over the years to go up and down, back and forth, losing a few pounds here, then gaining a few back. And each time that happens, there is more physical and mental strain on your body.

Every time you gain weight back after a weight loss, there are subtle changes going on in your body — and many researchers believe that the over time, all those changes can add up to some serious health risks. These include:

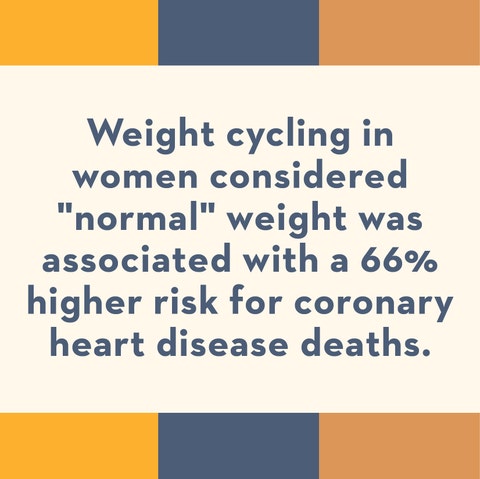

✔️ HEART DISEASE: In a 2019 study done in conjunction with the American Heart Association (AHA), researchers found that a history of weight cycling was associated with lower score on the AHA’s Life Simple 7, which measures the risk of cardiovascular disease through seven categories, including BMI, cholesterol, blood pressure, blood sugar, smoking, physical activity and diet. Though it’s possible there are outside factors such as genetics that influence both the urge to diet for weight loss and the risk of heart disease, researcher Brooke Aggarawal, Ed.D, assistant professor of medical sciences at Columbia University Medical Center, points out that there was still a very clear connection: “Not only was weight cycling associated with a poor cardiovascular health, but we found a dose response, too: Each additional episode of weight cycling was associated with a further reduction on the overall Simple 7 score,” she says.

✔️ DIABETES: A 2018 Korean study that looked at nearly 5,000 non-diabetic subjects found that after four years, those who had the highest levels of weight cycling were at significantly increased risk of developing diabetes. And a large review published last year confirms that for people who are average weight, weight cycling appears to increase the risk of developing diabetes. That said, the science is less clear when it comes to those who are considered clinically obese: A long-term Korean study found that people with obesity who experienced more weight cycling were actually less likely to develop diabetes than other study participants, which could indicate that, at least in terms of diabetes, the benefits of losing weight — even if it is inevitably gained back — might outweigh the risks of yo-yo dieting.

But some health experts say it’s not so simple. “The relationship of yo-yo dieting to diabetes is complicated and varies over time,” says Paul Ernsberger, Ph.D., a professor of nutrition at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, who explains that the decreases in blood sugar during weight loss are eventually regained, along with an increase in liver fat, which can make diabetes worse. “Because diabetes type 2 is a lifelong condition, the long term is what counts. The outlook for repeat dieters is not favorable even if short term results appear to be good,” he says.

✔️ MUSCULOSKELETAL DECLINE: The more times you cycle through diets, the weaker you may become as you get older. A 2019 study found that people who are “severe weight cyclers” are six times more likely to suffer from low muscle mass, and five times more likely to develop sarcopenia, a musculoskeletal disorder that makes you frailer and more likely to suffer from falls and fractures as you age.

✔️ GALLSTONES: Carrying a lot of body weight is one of the risk factors for developing gallstones (masses of cholesterol, bile and calcium salts that build up in the gall bladder, causing severe pain). But according to a report in the Journal of the American Medical Association, losing and gaining weight can also increase the risk: ”Large swings of body weight, especially the phase of weight recovery, are particularly sensitive to the accumulation of body fat and to the development of metabolic abnormalities, including insulin resistance, and thereby may facilitate gallstone formation,” the report states.

What happens your body every time you lose and gain weight?

There is still a lot of research being done to parse out exactly what happens every time you lose and then regain weight. But what we do know is this: After weight loss, your resting metabolism decreases, meaning that your body burns off fewer calories just going about your daily business of breathing, sleeping and digesting. And those changes tend to remain even after you’ve gained back the weight.

Then there’s the Imagine you drop a rubber ball. When it bounces back up, it actually goes higher than where it started out. Now, think of that ball as representing risk factors such as blood glucose and cholesterol levels — when you regain the weight you lost, all those numbers bounce back higher than where they were at the start, at least temporarily, Aggarawal explains. “Over time, the continuous fluctuation stresses the cardiovascular system, and you wind up in a slightly worse position than you were at baseline,” she says.

The third main factor is the increase in visceral fat: When you regain weight after a diet, the weight tends to come back not as muscle, but as fat — and much of that is visceral fat that encases your internal organs, Aggrarwal explains. “This type of fat is strongly associated with cardiovascular risk compared with other areas of the body where you may gain weight, such as the legs,” she says.

How to care for your body without dieting

There’s a revolutionary idea being espoused by anti-diet culture proponents, body positivity activists, and Health at Every Size advocates in a growing anti-diet movement: If you have to restrict your diet and bust your butt to lose that 10 pounds, only to see them slide back on as soon as you eat “normally” again, then perhaps it’s a sign that your body doesn’t want to be that weight.

Eating food that makes you feel nourished and that you enjoy — without counting the number of calories or carbs — may be the key to remaining at a steady weight, neither up nor down, stabilizing both your emotions and your health. “When people shift behaviors around food and eating and movement and stress management and sleep, even when their weight stays exactly the same, we see a decrease in the disease risk and an improvement in health,” says Alissa Rumsey, R.D., a certified intuitive eating counselor and author of Unapologetic Eating. “Intuitive eating is about taking care of your body rather than trying to punish or control it.”

“A lot of people think there’s an all or nothing way of eating,” adds Rumsey. “It can really hold them back in life — I know of so many people who won’t do things because of their bodies, they’ll say ‘When I lose the weight, then I’ll start dating or go on vacation or get my master’s degree!” Imagine if you decided to go ahead and just do those things, no matter what the numbers on the scale said.

After 40 years of dieting, Perlman says she still puts a lot of thought into her food choices, and thinks she always will, but she’s focusing these days on eating for energy and health, rather than weight loss. “I know now that you can be attractive, stylish and beautiful at any size,” she says. “I wish someone had told me that when I was younger. If I could go back, I would tell myself to learn what my strengths were and what made me wonderful and focus on that rather than the things I couldn’t change.”

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

[ad_2]

Source link