In the Bronx, a Face Lost in Time

[ad_1]

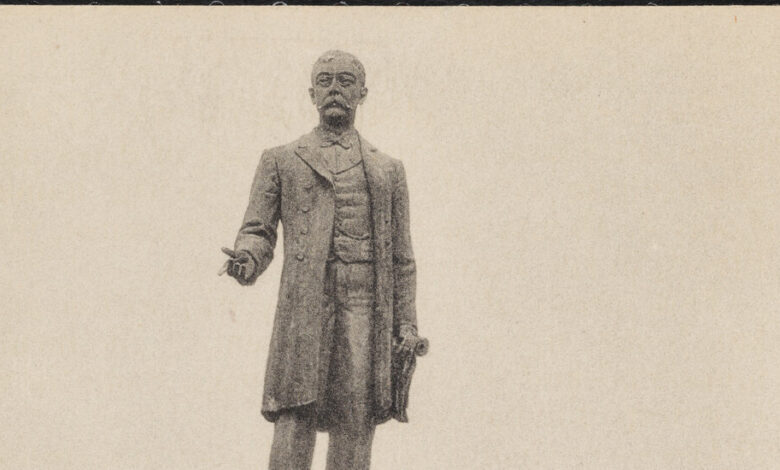

Fame can be fleeting for any of us, but in the case of Louis J. Heintz, a formerly celebrated New York City streets commissioner, injury has been added to the insult of increasing obscurity. In the decades after a memorial was dedicated to Heintz in a Bronx park in 1909, the graceful bronze allegorical figure of Fame that adorned the monument suffered multiple violations that are only now being remedied.

The lithe female statue originally stood on the monument’s steps, reaching upward to inscribe lofty words into a granite pedestal on which stood a sculpture of Heintz. By 1935, the palm frond Fame carried was loose, and city government removed it, noting that “it made easy prey for vandals.”

In 1971, Fame was mugged of her bronze pen. And later, while minding her own business in Joyce Kilmer Park, she sustained enough further damage that she was removed for her safety. But in 1980, while the statue was in a city storage facility at Rice Memorial Stadium in the Bronx, thieves broke in and violently cut off her head, arms and feet.

Now Heintz’s Fame is finally being restored. But the project has proven uncommonly tricky, as nobody knows what the decapitated figure’s face looked like. Because the figure faced the monument’s base, all known photos show Fame only from behind. And it turns out that the Public Design Commission, the municipal agency with authority over art on city-owned land, has a different conception of Fame than John Saunders, the artist charged with actually shaping clay with his hands to sculpt the new head.

Mr. Saunders initially crafted a lean, elegant face based on that of an angel he had previously created for a private client. But the commission felt it looked too contemporary. The sculptor adjusted the facial features in response to two rounds of feedback, and now, alas, Fame’s head “is in this transitional phase where I don’t really like it,” said Mr. Saunders, the Parks Department’s monuments conservation manager since 2007. “It lacks any spirit right now,” he said — “a sense of spirit that can leave people feeling inspired, uplifted.”

Heintz, a German-American born to wealth, got his start in his uncle’s Bronx brewery, had the good sense to marry the daughter of a millionaire brewer and in 1890 was elected the first commissioner of street improvements for the 23rd and 24th Wards of New York City, a section of the Bronx that had been annexed to the city in 1874. Before dying in 1893 of pneumonia, Heintz helped set in motion the construction of the Grand Concourse, the great boulevard built atop a ridge running north-south through the borough.

The man tapped to craft the statuary for Heintz’s memorial was the French sculptor Pierre Feitu, a member of the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris who later created sculptures for a French memorial to the New York-reared sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

At the opening of the Grand Concourse in 1909, dignitaries gave their speeches from the steps of the Heintz memorial. For the current restoration, conservators made a plaster cast of those steps and of the bottom of the pedestal, which they placed in a Parks Department workshop beneath the Brooklyn War Memorial in Cadman Plaza Park. They then moved Fame’s several-hundred-pound torso around with a small crane to determine the appropriate orientation of the statue.

“It had no arms or feet, it was just this floating chunk, so getting it attached to the cast of the monument was the biggest challenge,” Mr. Saunders said. “If she’s tilted backwards it’s going to look terrible, like she’s a little drunk writing these words.”

Feitu sculpted Fame as a vigorous woman of about Mr. Saunders’ height, six feet, which allowed Mr. Saunders to use his own arms to determine the proper scale. For reference in creating an appropriately feminine form, he made a cast of the arm of a female intern, Odette Blaisdell. The arms and feet he modeled in clay were then cast in bronze at the Bedi-Makky Art Foundry in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn.

Jonathan Kuhn, the Parks Department’s director of art and antiquities, said that when he came on the job in 1995, about a dozen damaged sculptures were languishing in storage. Under the Citywide Monuments Conservation Program, founded in 1997 as a public-private partnership, all but Fame have since been repaired and put back on display. A bronze lioness went home with her cubs to the Prospect Park Zoo. A World War I doughboy, whose helmet had been bashed in and his bayonet stolen, was discharged back to Macombs Dam Park. And a discus thrower that had been violently assaulted underwent major surgery and was returned to Randalls Island Park.

The discus thrower “was missing his discus and private parts,” Mr. Kuhn said. “We found a plaster mold of his penis in our storage compound, and we were able to very faithfully recast it along with his arm and discus.”

Putting a face on Fame has proven a special challenge.

“We’re trying to channel the aesthetic of the time so that the finished version will resemble as closely as possible the work of the original artist” and evoke an early 20th-century aesthetic, Mr. Kuhn said. “There’s no perfection here because we don’t know what she looked like.”

For reference, photographs were assembled of other sculptures by Feitu, but Mr. Saunders found them of limited help. The allegorical figures were in a “completely different style,” he said, while a portrait bust of a middle-aged woman was “not necessarily very telling because portraiture is a completely different animal than allegorical figures.”

His preferred approach was “to try to make something beautiful on its own in the spirit of Feitu and be done with it,” he said. But members of the design commission’s Conservation Advisory Group — two art historians and a conservator — wanted changes to the face he sculpted.

The group “noted the beauty and skill in John Saunders’ work, but felt that the face looked very contemporary,” Keri Butler, the commission’s acting executive director, wrote in an email. The members suggested he refer to Feitu’s other work “and similar artworks of the period and style,” she added, “and members recommended that the restored face be plumper, with a straighter nose and thinner lips, in keeping with typical allegorical sculptures of the early 1900s.”

Mr. Saunders has complied, but he said that implementing such specific instructions was like working as a sketch artist for the police.

“You know how those drawings, they maybe look like the person, but they have this sketchiness about them that they don’t really look like a complete portrait?” he said. “I think the head has kind of taken on that quality.”

Ms. Butler said that the design commission’s review was “a team effort” resulting from “dialogue with the Parks Department and other stakeholders and is not prescriptive.” And Mr. Kuhn of the Parks Department said his agency agreed with the commission’s suggestions.

But Mr. Saunders sounded constrained by the specificity of the guidance.

“There’s a review process, and there are people who are above me in the chain who get to decide what’s going to be done in the end,” he said, adding, “because of the way this is working out, I’ve kind of had to divorce my aesthetic a bit and just be like, ‘All right, fine, I’m just a tool. You say what you want and then I’ll do it.’”

Nonetheless, the restoration is still a work in progress. When the coronavirus hit last spring, Mr. Saunders began working from home. To do so, he drove to Connecticut with Fame’s unfinished clay head in the passenger seat beside him, secured with a seatbelt.

One day a few weeks ago, he chauffeured the reworked head back to the Brooklyn workshop to unite it with Fame’s reassembled bronze body. For the first time, the bronze castings of the statue’s arms and feet, as shiny as a new penny, were attached to the weathered green torso. And though she was as yet a patchwork figure of disparate parts, a distinct grace of movement could already be discerned.

Mr. Saunders climbed a ladder, and the metal rod poking from Fame’s neck made a squeaking sound as he twisted the clay head onto the bronze neck. He stepped back and regarded the assembly impassively.

Did the new head lack spirit, as Mr. Saunders believed?

“I think he’s refining certain details,” Mr. Kuhn said. “I’m looking at a slight adjustment to the nose.”

The next steps, once the head is completed, will be to make a rubber mold off it and create a plaster cast from that mold. At the foundry in Greenpoint, the cast will be pressed into sand, creating a negative impression that will receive the molten bronze. The finished product will be a bronze version of the head that Mr. Saunders modeled in clay.

The figure’s bronze head and appendages will then be welded into place, and Mr. Saunders will give the entire figure a uniform patina to match that of the Heintz statue.

“He’s a perfectionist,” Mr. Kuhn said of Mr. Saunders. “It’s a good thing, to get it right and to satisfy him as well as others who are commenting.”

Ultimately, sometime this year, the allegorical figure is expected to be reunited with Heintz in the Bronx, after more than 40 years of separation. Originally, only a single dowel joined her to the pedestal, so the plan is to provide added security by reattaching her at three points. With any luck, this time Heintz will keep his Fame intact.

For weekly email updates on residential real estate news, sign up here. Follow us on Twitter: @nytrealestate.

[ad_2]

Source link