The Board, the President, and the Whistleblower

[ad_1]

In July, Kentucky State’s president, M. Christopher Brown II, resigned over questions about the institution’s flagging finances and whether he had fully informed the Board of Regents about the problems. The institution is facing a budget shortfall of at least $21 million for the current fiscal year, including nearly $16 million in unpaid expenses from the previous fiscal year.

On the surface, the situation is not unusual in today’s higher-education landscape: A small, public institution runs short on cash, the president takes the blame, and he’s forced to leave his job. But in this case, the president was previously accused of misspending at another institution, there’s evidence that the board ignored signs of trouble, and a whistleblower was ousted from the board for speaking out.

These are just the latest problems at Kentucky State, which enrolls about 2,000 undergraduates, nearly half of them part-time, according to federal data.

In 2016, the university’s financial problems led to a state-ordered restructuring plan, along with a significant increase in state appropriations. Brown’s hiring in 2017 was controversial and followed by the faculty voting no confidence in both the board and its chair. And the current problems have raised questions about the role of the university’s Board of Regents.

Now, some lawmakers, who helped bail out the university in 2016, are questioning whether the institution should remain open. “So the financial case to be made is that there should not be a Kentucky State,” state Sen. Christian McDaniel, a Republican and chair of his chamber’s committee on appropriations and revenues, told the Associated Press.

For the second time in five years, the Council on Postsecondary Education will examine Kentucky State’s finances and administration and recommend changes to elected officials.

Aaron Thompson, president of the state’s Council on Postsecondary Education, was interim president of Kentucky State before Brown was hired and is now overseeing the agency’s examination of the university.

Thompson said much of the institution’s budget shortfall can be blamed on raises or one-time bonuses for current mid- and upper-level administrators.“Personnel spending has gone up tremendously,” he said.

The news of the money problems is in contrast to previous news announcements from the university which said the institution was on solid financial footing. An April statement from the institution said its independent audit found a $2.3-million surplus for fiscal-year 2020.

In an interview, Brown cited numerous reasons for the sudden decline in the university’s financial situation, including missteps by the university’s former chief financial officer, who left the institution in the spring. That official did not immediately respond to requests for comment Tuesday afternoon.

Brown was hired by Kentucky State in 2017 after a decade-long career in higher-education leadership, many of those years spent at historically Black institutions like Southern University and Fisk University.

In 2010, Brown became president of Alcorn State University, a historically Black land-grant institution in Mississippi. He resigned in late December 2013, after an Associated Press investigation found that he had spent nearly $90,000 in upgrades to the presidential residence without going through the proper bidding process.

When Brown was announced as the president at Kentucky State, there was widespread dissent from the faculty, who voted no confidence in the Board of Regents over the search process and the lack of qualifications of the finalists. Many were also upset that Thompson, then interim president, was not among that final group.

“He would have been a natural for the university at the time because he was a Kentucky native,” said state Rep. Derrick Graham, a Democrat and an alumnus of Kentucky State. “He knew how to work with the legislature, and he knew how to build relationships.”

Thompson said the financial issues facing the university when he took over as interim president were similar to the current problems and resulted in personnel cuts and dropping some 600 students who had unpaid bills. That move added to an already steep decline in enrollment — 44 percent between 2010 and 2015 — and tuition revenue.

The administrative changes were necessary for the financial health of the university, but they were also prescribed by a 2016 law requiring the university to develop a management plan in consultation with the Council on Postsecondary Education. The university was required to provide regular updates to the General Assembly on its performance as well.

Despite some calls at the time to close the university, Thompson and others convinced the state to give Kentucky State the full amount of land-grant money it was due. With that money, Kentucky State now receives more than $9,800 per full-time student — more than any other public university in the state.

Thompson understands the challenges Kentucky State faces, but is also concerned that lawmakers may overreact to the situation.

“It’s going to be the job of CPE and the board to address financial issues,” he said, “but the greater need is to get the message out why Kentucky State needs to be a strong institution to serve the population of the state.”

Despite some initial opposition to Brown’s hiring — three board members voted against it — there were no outward signs regents were unhappy with the president’s performance.

A January review of Brown’s performance by Charlie Nelms, a consultant with the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges and former chancellor of North Carolina Central University, gave him generally high marks. But it also called for “a comprehensive review of university budget development and monitoring processes to ensure transparency, accountability, and alignment with best practices in higher education.”

In an email, Nelms declined to comment further.

In June, just a month before his resignation, the regents extended Brown’s contract and awarded him more than $40,000 in performance bonuses. Elaine Farris, the current chair of the board, did not respond to a request for comment.

There were other indications the board knew much more. For fiscal years 2015 through 2019, the university’s auditors faulted the institution for not having “adequate controls in place over financial reporting to allow for timely, accurate financial reporting.”

Chandee Felder, who was the elected staff member on the board, told The Chronicle she had communicated frequently with several other board members about the university’s dire financial situation. Other staff members at the university communicated the problems to her, Felder said, and she relayed that to Farris and other regents, who welcomed the information and encouraged her to share it with them.

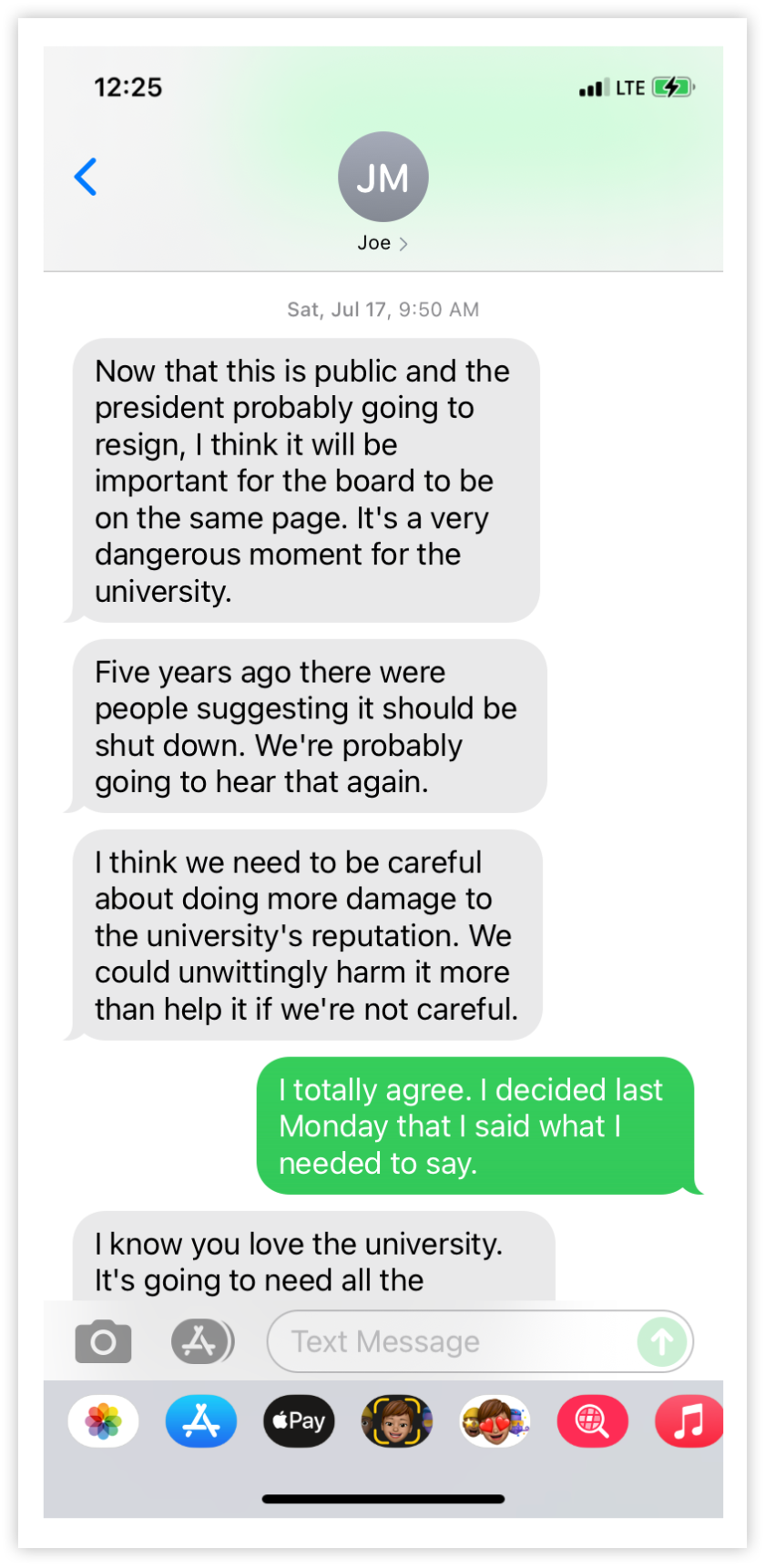

In text messages that Felder provided to The Chronicle, she tells other board members, including Farris, about the president’s plans to change or cut staff and her concerns about how money was being spent.

Courtesy of Chandee Felder

Felder said she had to speak up when Farris was quoted in news articles saying the regents were not aware of the financial troubles. She also sent a letter to Gov. Andy Beshear, a Democrat, about the university’s financial situation, as well as the state’s attorney general.

Felder was fired from her position in mid-September the day before her allegations were published by a news article in The State Journal, in Frankfort, Ky. A letter from the university’s director of human resources said that Felder violated university policy by sharing confidential information and breaching the conflict-of-interest policy.

Felder has hired an attorney and filed a lawsuit against the university.

“I kept telling them we don’t have any money,” Felder said. ”I don’t see how we’re making it day to day.”

The University of Louisville, for example, faced numerous state and federal investigations in the middle of the last decade over allegations it lured men’s basketball recruits with sex, misused federal grant money, failed to enforce conflict-of-interest rules, and padded then-President James Ramsey’s pockets with money from the university foundation that he also led. While then-Gov. Matt Bevin overhauled the board and convinced Ramsey to resign, there were no calls from lawmakers to close the institution.

Graham said those who are calling for the university to be closed may not be familiar with its important role in educating Black Kentuckians.

The university has been part of the economic engine of the region and helped to increase the Black middle class that contributes to the state’s economy, Graham said.

“The bottom line comes down to the students,” he said, “we owe it to the students.”

Dan Bauman contributed to this article.

[ad_2]

Source link