How This Cardiac Nurse Ignored Her Heart Attack Symptoms

[ad_1]

I have worked for six years in the cardiac unit at Rose Medical Center in Denver. As a cardiovascular registered nurse (CVRN), I’ve cared for people of all ages, sizes, ethnicities, and backgrounds who have had chest pain and heart attacks. I know that heart trouble comes in many forms, and that sometimes it’s predictable and sometimes it’s surprising. I know exactly what the warning signs are, so I’ve rolled my eyes at people who stroll into the emergency department reporting chest pain that has been going on for two days. Why would anybody risk his or her life by delaying treatment?

Then I became one of those people. And I let mine go on for six days.

Michael Wahl, MD, cardiologist, Rose Medical Center: “300,000 people a year die from sudden cardiac death at home. So they have either sudden symptoms or symptoms they didn’t recognize.”

1 a.m. Saturday: start of symptoms

One Saturday last February, I woke up in the middle of the night with a dull, burning ache radiating down my left arm. I figured I had slept on it wrong—I was only 47, and fit!—so I repositioned myself in bed and tried to sleep. But the pain didn’t go away. So I walked around a bit and gave the cat a snack, and still the pain was there. I also felt sweaty and vaguely nauseated.

Top four symptoms of heart attack in women

- Chest pain

- Pain or discomfort in one or both arms

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating, nausea

Yes, Jennifer was experiencing three out of four.

Sean, the charge nurse on my unit that night, had been on the job for 20 years; if my heart stopped, he was just the guy to start it back up again. I called him at the hospital at 3 a.m., told him my symptoms, and asked him, half jokingly, if he thought I was having a heart attack. In his straightforward style, he said, “Well, it doesn’t sound good. Are you pale?” I walked into the bathroom to check. I wasn’t pale—I was white. Maybe even a little gray. That’s when the panic set in. Which is bad for your blood pressure, by the way. I popped an aspirin and drove myself to my hospital’s emergency department.

🚨 If you have any symptoms of a heart attack, you should avoid driving and dial 911.

I felt at home, and I trusted my coworkers, so the panic started to recede. Bonus: The EKG came back perfectly normal, and my heart rhythm was beautiful. The panic receded a bit more. My levels of troponin—an enzyme that signals damage to heart muscle—were normal as well. My panic was soon replaced with boredom: I had to hang around for a few hours for more blood work, but at that point I knew it was a false alarm. I slept.

The day nurse, Kellie, showed up in a couple of hours to check my troponin levels again. We had a laugh about how overly cautious nurses were. After she was done, I removed all my EKG stickers and got dressed and was practically in the parking lot when the second troponin reading came back. Now my levels were slightly elevated. I was admitted to my own cardiac unit. About four hours had passed since the arm pain and nausea had awakened me, so I decided it was time to call The Boyfriend. He was clearly irritated that I had waited so long to contact him.

Lance Harlan (The Boyfriend): “The thought kept going through my head: I’ve finally found a woman I love, and she’s going to drop dead on me.”

But hey, I hadn’t called him sooner because I hadn’t wanted to worry him over nothing. He met me at the hospital, equally concerned and exasperated.

My first doctor was convinced that my just-above-normal troponin numbers were a false positive. My arm pain was probably a pinched nerve. After all, I had zero risk factors—I exercised regularly, my cholesterol numbers were excellent, my body mass index was low and lean, and I had no family history of cardiac disease. So I was a perfectly healthy heart attack victim with every reason to delay, doubt, and just maybe die.

Heather Harris, director of cardiovascular services, Rose Medical Center—Jennifer’s superior, friend, and mentor: “We see a lot of people who have been waiting for the chest pain to just go away on its own. And all that time their hearts aren’t getting enough blood! Time is muscle. The faster you get treatment, the more of it you can save.”

My doctor told me, “We’ll cycle another troponin, give you a treadmill stress test this afternoon, and get you out of here before sunset.” That all sounded good to me…until the next troponin came back even more elevated. They canceled my stress test—no need to bring on a heart attack—and booked me overnight in the hospital.

Lance and I sat around killing time for most of the afternoon. I didn’t allow any other visitors: I didn’t want my staff to see me all gowned up as a patient, especially one experiencing what I thought was a massive false positive. I had a symptom-free night, enjoying a forced mini vacation even if it was in a hospital room.

1 p.m. Sunday: 36 hours since start of symptoms

On Sunday I aced my stress test and was cleared for discharge—finally. But there were still worries. My discharge doctor said there was no good reason for my pain and elevated troponins. (That is, aside from the one I kept talking myself out of: That I was having a heart attack, maybe even right then.)

Dr. Wahl: “Most heart attacks damage the heart within 12 hours. That’s why we try to do things so fast in cardiology. The arteries in Jen’s heart were probably opening and closing during the course of the few days beforehand. So during those 36 hours, she might have been intermittently having a heart attack.”

1 a.m. Wednesday: 96 hours since start of symptoms

Instead, I doubled down on the pinched-nerve theory. So much more reassuring than the myocardial infarction theory! I slept fitfully for four hours, then dragged myself out of bed and went to work. It was Valentine’s Day—you know, the holiday that’s all about your heart. I mentioned to Heather that I was feeling like crap again, and she suggested that I make my follow-up appointment with my general practitioner and perhaps book a massage.

Dr. Wahl: “The ejection fraction [EF] is the percentage of blood that pumps with every heartbeat. If your heart is normal, it should pump about 60% of the blood with every heartbeat. Later on in her treatment, when we tested Jennifer’s EF, it was about 45%. That can make you look and feel like hell.”

I scheduled an appointment with my GP for the next morning and one with my massage therapist for Saturday. I swallowed an ibuprofen, with minimal effect. I went to meetings and helped the floor nurses, all the while struggling to catch my breath and feeling unsettled.

Heather Harris, mentor: “We all want to think of reasons this couldn’t be a heart attack. You don’t want to be sick. But if something doesn’t feel right, have it checked out. You can be lucky only so many times.”

Around 1:30, I felt I’d had enough. I told the charge nurse I was leaving early. But then a patient fell. And there was an unhappy family that I had to visit with. And I helped troubleshoot some staffing issues. By the time I got into my car to drive home, it was 4:00.

❗Repeat: Do not drive a car when you’re having heart attack symptoms!

I took more ibuprofen when I got home, tried some stretching, rolled my shoulder blade around on a tennis ball looking for relief. Nothing. I took a hot bath, downed more ibuprofen, and crawled into bed. Still no relief.

1 a.m. Thursday: 120 hours since start of symptoms

I had never experienced pain of this sort before. With a pulled muscle or a pinched nerve, there’s usually some relief with OTC painkillers—you can get into a comfortable position in bed and sleep. Not this time. Whatever the position, the burning, unsettling ache was there. Getting no help from ibuprofen, I tried acetaminophen. (Yeah, nurses play pain-pill bingo too.) I curled into a ball and slept for about three hours. When I woke up, the pain had migrated away from my left arm and shoulder and planted itself squarely under my left breast: directly over my heart.

Thursday morning, I was up early and at work, really for no other reason than that I felt the need to keep moving and be around people. I reached the cardiac floor about 6:45. I told Heather I still felt like crap. Where are you? she texted. On the floor of my office, I responded. The only way I could feel remotely comfortable was lying flat with my left arm over my head. Heather ordered me to go straight to the emergency department. Nah, I responded, I’ll be fine.

Finally, 9:30 arrived and I walked next door to my doctor’s office for my appointment. She could see how uncomfortable I was. She took a repeat troponin level, gave me an EKG, and ordered a neck X-ray and an outpatient echocardiogram. I assume the EKG was normal, because I was sent on my way.

I walked down the hall to book the echo—but I didn’t tell the scheduler I was having chest pain right that minute, so she booked it for three weeks out. I shrugged and went back to work.

Meanwhile, Heather wasn’t buying my denials. She asked Jeff, one of our echo techs, to skip his lunch and give me the test. We chatted casually throughout the exam—he was pointing out this and that, like a tour guide. But at one point he went quiet. He finally broke the silence, saying, “You know, I really hope we find something, because at least then you’ll have an explanation for the pain.” I knew then that he’d found something.

Dr. Wahl called within 30 minutes and asked me to meet him to go over the findings. He showed me the echo images, using words I knew too well: “wall-motion abnormality” (heart wall malfunction caused by dying muscle tissue); “decreased ejection fraction” (heart-pump misfire); “cardiomyopathy” (heart-muscle disease). These familiar terms suddenly had new and horrific meaning when used to describe my heart.

He mentioned a few potential diagnoses: takotsubo cardiomyopathy, a temporary stress-related weakness of the heart muscle; a virus; or (a remote possibility) spontaneous coronary artery dissection, a.k.a. SCAD. The last was a killer of relatively young, healthy women (like me). That just couldn’t be my diagnosis!

Dr. Wahl told me I’d immediately be going into the heart catheterization lab, where they diagnosed and treated arterial blockages. His sense of controlled urgency told me everything I needed to know. He said he’d give me a few minutes to process and make phone calls. Step one: Cry over the phone while talking to Lance and then my parents, 1,700 miles away in New Jersey.

1 p.m. Thursday: 132 hours since the start of symptoms—treatment begins

Things started to move very quickly. In the cath lab, three nurses descended on me. One started an IV; one drew blood for more lab tests; one started shaving my groin so they could send a catheter up my femoral artery. Heather ran in and gave me an aspirin to chew. Bitter, right? Just like this turn of events in my otherwise healthy life.

A Texas study found that chewed aspirin reaches the bloodstream seven minutes faster than swallowed aspirin, encouraging blood flow and just maybe saving heart tissue that would otherwise die.

“Oh my God,” I said to Heather. “Do they think I’m having a heart attack?”

“Yep,” she said, as if I had asked her if we could get pizza for lunch.

For the first time, I realized I might not survive this. But everyone in the cath lab just kept saying, “We’ve got you, Jen, we’ve got you.” I’d failed to take care of myself—they’d do it for me.

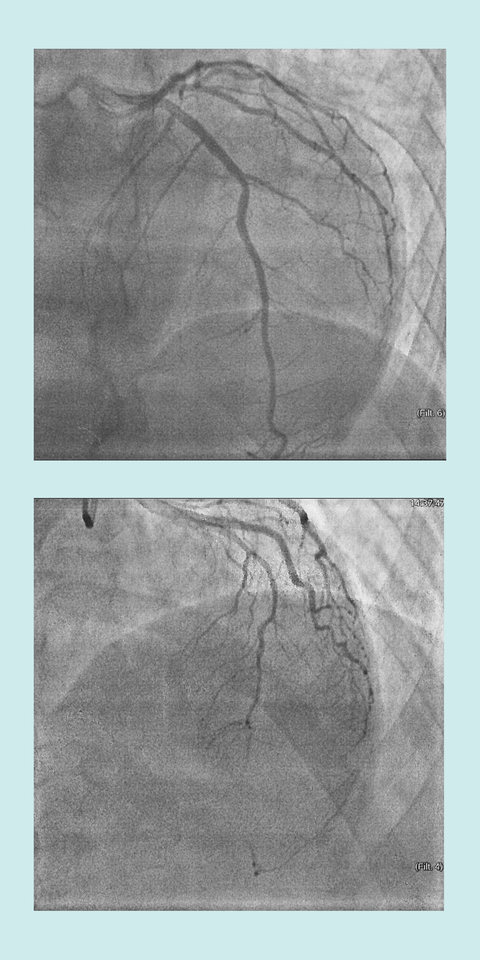

When Dr. Wahl got a look at my heart vessels during the angiogram—in which they shoot dye into your arteries and view blood flow via X-ray—he knew I was in trouble. He called in two of his colleagues, and Heather joined them.

Looking at the images of my failing heart, Heather asked, “Where is her LAD?” She meant my heart’s left anterior descending artery, which supplied blood to the left ventricle—the pump. Lose that blood flow, and you likely lose your life—which is why they call the LAD the widow(er)-maker.

One of the doctors said, “I think it’s gone.”

The diagnosis was in fact SCAD, exactly what had worried me. Muscle fibers within my LAD had shredded, blocking the artery like a flag sucked over an air-intake vent. A clot had formed, and blood flow had stopped dead. I would have too, except that my brilliant, strong heart had begun forming collateral circulation—alternate routes through smaller blood vessels—to keep my heart muscle alive. Athletes develop collateral circulation during the stress of exercise, or it can happen spontaneously during a heart attack. Either way, it might have saved my life.

Boyfriend Lance Harlan: “Unless you’re in the medical world, you don’t realize how smart the heart is. It was basically saying to Jennifer, ‘I can’t seem to make my way down this highway. I’m going to make a new highway to get there.’ Her heart fixed itself. In other words, she was lucky.”

I blame myself for dismissing my symptoms and avoiding treatment—but I should also take credit for what I was doing right. I’d been strengthening my cardiac muscles with exercise, regularly jacking my heart rate up to 160 beats per minute in Spinning class—and that may be why those collateral blood vessels were available. My gym membership is so worth it.

Usually when there’s an arterial blockage, the cardiologist will insert a balloon, via catheter, to open up the artery, then shore up the opening with a mesh tube called a stent. But with SCAD, the artery is vulnerable to further shredding, and barging in with a balloon and a stent can close down more sections of it. Because my artery was closed downstream in a smaller portion of the artery, we opted for no surgical treatment at all. Dr. Wahl prescribed the anticlotting agent coumadin and a baby aspirin every day to keep my life-saving collaterals open and prevent new problems after the injury to my heart. Meds are keeping me going now that my LAD can’t.

I’m the textbook case of SCAD: female, 42 to 53 years old, with few cardiac risk factors. Nobody knows why 80% to 90% of SCAD victims are women. It could be hormones, or curlicue arteries, or inflammation, or genetics. But the symptoms are clear as day: chest discomfort, shortness of breath, nausea, light-headedness. (You’ll watch for those, right? Don’t explain them away like I did.) And all those symptoms were complicated by an advanced case of procrastination.

But that’s what women do. We think, Unless I have blood spewing from the artery in my neck, I’m fine. I can’t be sick. My kids need me. My coworkers need me. I don’t want to upset any of the people in my life.

In the recovery room afterward, I told Lance, “I could’ve died.” He said, “But if you had, then you’d just be dead, and you wouldn’t even know it. And I’d be the one who was suffering.”

Heather Harris: “Women especially don’t recognize the symptoms of a heart attack. They don’t have the classic ‘elephant sitting on your chest,’ the way men do. They just don’t feel right. Their shoulders are uncomfortable, or their backs hurt. And then there’s the sense of denial: I have too much to do to have a heart attack right now!”

My heart-building workouts may have saved me. But aside from building up your heart muscles with exercise, don’t do what I did. Don’t convince yourself your symptoms are “nothing.” Don’t worry about looking like a drama queen in the emergency room. Don’t worry about inconveniencing people, or about leaving work early, or about what your boyfriend, husband, boss, kids, or parents might think.

Don’t wait. Live.

Note: All photos were taken prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

[ad_2]

Source link