The Redemption of Frederick Shegog

[ad_1]

The lean 38-year-old stood near the breaker box, shut his heavy-lidded eyes, and said a prayer. After some deep breaths, he started the timer on his phone. Then he filled the low-lit room with his voice.

“Thank you for allowing me to be here.”

Shegog imagined an audience before him, but there was just a wall covered in crinkly, white waterproof plastic. He rehearsed there often, rewinding the past.

“ … I remember thinking I wasn’t good enough. …”

Shegog had enrolled in college six times and dropped out six times. He was a Black man in a nation where nearly twice the share of white men as Black men have a bachelor’s degree. Now, on his seventh try, he was pushing closer to his diploma. Without it he couldn’t live the life he wanted. Without it he would keep carrying the shame of failure.

“… Everybody in this room has had some type of pain in their life. …”

It was after midnight. Shegog paced the concrete floor. Self-doubt had gripped him for years, but public speaking was helping him loosen that grip. Halfway through an anxious semester, he was struggling in Spanish 101, which he had to pass to graduate.

Something felt off as he worked through his speech. So he reset the timer and started again, summoning the spirit required to tell the story of how he had reclaimed his life. But anyone who listened would know something important: The story wasn’t his alone.

It began on a summer night in 2016 when he drank a bottle of vodka and passed out in downtown Philadelphia. Sprawled on the pavement, he was about as far away from college and its fabled rewards as a man could be: homeless, alone, and untethered from anyone who could help him.

Then a stranger appeared.

Shegog, who hoped to become a newscaster, idolized Jennings the way other kids idolized Michael Jordan. He saw the anchor as the embodiment of what he hoped to be: confident, eloquent, knowledgeable, professional. Someone who belonged in every room and wore tailored suits.

His parents divorced when he was a year old. His father moved away and wouldn’t see him again for almost two decades.

Growing up, Shegog was close with his mother, Joyce Barr. She admired her only child’s gentle spirit but worried about how he would fare in a not-so-gentle world. On weekends they watched football games together on TV, often eating her homemade baked chicken, greens, and cornbread. Sometimes she tickled him and called him “Freddie Betty.”

But they shared difficult moments, too. For years, Barr, who struggled with mental-health problems, drank, and smoked weed. She quit both when he was 10. After completing an addiction-treatment program, she often took him to her Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings. Before he ever solved an algebra problem, read The Autobiography of Malcolm X, or kissed a girl, he learned all about support groups.

Courtesy of Frederick Shegog

Those meetings, in which résumés didn’t matter, shaped Shegog’s understanding of the world. He saw lawyers and homeless folks sitting side by side. He heard people offer to take in a man who had lost his home, everything, to addiction. Though no support group was perfect, he saw that they could give people strength they might otherwise lack.

Shegog himself would come to feel that strength when he was 12. After telling his mother’s boyfriend that he wanted to stab himself, he ended up in a psychiatric hospital. By then he was dealing with anxiety and ADHD, and had been getting high from an asthma inhaler since he was nine. During his week at the psychiatric hospital Shegog bonded with white kids from affluent families who shared his diagnoses. They talked about the meds they were on, the stigma of mental illness. When his mother came to take him home, he cried because he wanted to stay.

Though Shegog had friends growing up, he didn’t fit in. Neighborhood kids bullied him. In the locker room at basketball practice, teammates pelted him with shoes. At his mostly white high school, students stuffed him into a trash can. Though sometimes suicidal, he acted like everything was fine so as not to worry his mother. His grandfather, who helped raise him, would say, Don’t make her plate full.

Shegog supported her in his own way. Though living in Pittsburgh Steelers country, he declared his allegiance to the Green Bay Packers in 1996 after Brett Favre, the team’s star quarterback, announced that he was seeking treatment for addiction. Like Mom did, Shegog thought. He wore green and gold year-round as a tribute to her sobriety.

Barr, who had a bachelor’s degree, expected Shegog to go to college. But money was tight: Sometimes he ate and she didn’t. A full-time social worker who later worked at a treatment center, she bought him Air Jordans and sent him to sports camps, with help from his uncles and grandfather. But there was no saving for college.

His high-school years didn’t put him on a postsecondary path. Following a rift with his mother, Shegog spent time in a psych unit before moving in with his aunt, who taught him how to share a home with a family, giving him some stability. Still, he graduated with no plan, convinced that he was stupid.

Shegog spent years playing video games and working low-paying jobs. Drinking and weed, once a weekend habit, became a regular thing. He lost his 20s in a blur of booze, rehab centers, shelters, psych wards, lost jobs, and bad relationships. He despaired when he saw the Packers on TV, thinking he would never have the means to attend a game at legendary Lambeau Field.

After splitting with a longtime girlfriend, he got sober and moved to Philadelphia in 2014. He lived at a Christian shelter and recovery center, where he got a job sorting donated clothing the facility sold. He snagged designer blazers, Brooks Brothers shirts, and Gucci loafers. On Friday nights he dressed up and took the trolley downtown, with the Stylistics blasting in his headphones.

One night, Shegog called his mother from Center City. Though their relationship often frayed, it never broke. She worried about him, knowing how hard it was to shake addiction. Shegog was looking rich and feeling good that night, but she knew what was up. “You haven’t changed,” she said. “You’ve just got more stuff.”

She was right: After months of sobriety, Shegog was drinking again, not taking his meds. Because he had blown all his money on late nights at bars he couldn’t keep the apartment he briefly rented. He quit his job at the shelter, where he had been tutoring homeless men. For a while he lived with a woman he met in a psych ward, but after he failed to get another job she kicked him out.

Then, 14 years out of high school, he was homeless himself. He slept in an alley, panhandled at bus stops and outside the Ritz-Carlton, sometimes taking enough cash into his palm for liquor and a burger. Some nights he climbed into dumpsters, looking for bread, anything filling. Opening trash bags, he felt like the lowest thing on earth, praying he could swallow and keep down what he found.

On June 22, 2016, Shegog drained a bottle of Vladimir vodka, hoping to black out and not wake up. By the time he collapsed against an office building, he had lost his shoes. Late that night, a voice yanked him awake.

Sir!

He saw a Black man in running clothes, holding a pillow and a bottle of water. Shegog told him to let him die. Then he heard the man say this: Brother, you ain’t dying today.

First he needed clothes. In the center’s basement he plucked donated shirts and pants from bins. Then, while picking through a pile of stained underwear, he felt like he had hit a new low. He resolved to quit drinking and getting high for good. When he told his mother that, she said, I hope I don’t bury you.

Many days at the center were harrowing, but he took comfort from Susan Kaelin, a staffer who brought him Skittles, rubbed his back, and told him to get himself right so that he could help others. Their many deep conversations gave him hope, and he came to think of her as a kind of mother. One who saved his life.

After 78 days, Shegog, sober and determined, moved to a halfway house in Upper Darby, Pa., near Philadelphia. There he befriended an older man who gave him $20 for a haircut before he went to interview for a job at Panera. He was hired.

For $9.25 an hour, Shegog, then 33, greeted customers, refilled coffees, cleared trays, and wiped down tables. Working long shifts with teenagers five days a week was tough, but the job gave him a routine — and confidence. On the streets he had used his gift of gab to survive; at work, it helped him earn tips. And draw people to him.

People like Maryann Bruno and her cousin Mary Rose, who met at Panera once a month to catch up and crochet together. They were his first “Panera moms,” more than a dozen regular customers, all middle-aged women, most of them white, who became his friends and confidantes, often bringing him cakes and cookies. Bruno would ask Shegog how his mother was doing, and he would ask her the same. She made him a hat and scarf in Packers colors, and her cousin made him a matching blanket. He brought them Hallmark cards with notes he signed “Love, Freddie.”

Those relationships made him feel like someone again, helped him stay sober — he didn’t want to let them down.

One day Shegog met Kim Riley at an AA meeting. She was frank and down-to-earth, more than a year into her own recovery. When she heard him share with the group, he sounded angry but passionate. His gale-force voice moved her. Later, she dropped off some homemade chili for him at the halfway house.

Emily Cohen for The Chronicle

Riley — white, divorced, and much older — wasn’t seeking a relationship; neither was he. But they felt a connection. When he had to move to a shelter, in early 2017, she drove him there. Riley watched as the man behind the front desk was nasty to Shegog, who stayed calm. This guy is different, she thought.

Each week Shegog and Riley texted often and went to church together. Eventually, Riley asked him to move into her house, in Drexel Hill, a suburb of Philly. Shegog told her that though he loved her, it wouldn’t work: She was a homeowner with a college degree and a steady job as a clinical-appeals nurse. All he had were some trash bags full of clothes. “It’s not about what you have,” she told him. “It’s about who you are.”

That spring, Shegog moved in with Riley, who lived with two of her three grown children. He was attending AA meetings, taking meds, seeing a therapist. After a year of sobriety, he felt ready for college.

A bachelor’s degree, he believed, was his last shot at a better life. In his 20s he had enrolled at six different institutions, never lasting more than two semesters; drinking did him in each time. Without a degree, he feared he would end up managing a Panera, or working at a treatment center and boozing again.

So in the summer of 2017, Shegog, then 34, enrolled at the Marple campus of Delaware County Community College, or DCCC. He had secured federal aid and taken out loans. A state program covered the cost of books, supplies, and the bus pass he needed to get to and from the campus. And he enrolled in the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. None of it guaranteed that things would turn out differently this time.

On orientation day, Riley packed Shegog’s lunch and wrote a note on the napkin: “I’m so proud of you.” Wearing a Packers hat, backpack, socks, and shoes, plus a Harriet Tubman T-shirt, he walked around introducing himself to students half his age, saying he was happy to be there and be sober.

After taking placement tests, Shegog learned that he had been assigned to remedial courses. Thinking that “remedial” meant “advanced,” he called his mother to celebrate. She told him what the word meant, but he didn’t believe it until a student in the cafeteria confirmed that remedial courses were the lowest level. College had a language of its own, and he didn’t know the words.

Dejected, he took the bus home. That night he cried and told Riley he was stupid: “I ain’t doing this. I quit.”

If Shegog hadn’t been in a supportive relationship, his seventh try at college might have lasted a day. But Riley assured him that he was smarter than he thought. “Freddie, go to class,” she told him. So he did.

Days later, in English 025, a remedial course, Shegog got an assignment: Write about an experience that shaped his identity. The paper would be graded on content alone. Freed from fretting over grammar, Shegog described how he had gone from cleaning his Baptist church on weekends to doing things with men in alleys for money to buy alcohol.

The essay’s authenticity and vivid details impressed his instructor, Jamie Kelly-DiMeglio. One night she asked Shegog to stay after class. “There’s life in this paper,” she said. He shook with happiness, as if he had just broken through to a new existence.

Shegog sat with Kelly-DiMeglio after each class, listening to her feedback, refining his writing. Their chats often continued into the parking lot. He shared so much with her that one night she confided there was alcoholism in her family, too. She felt she owed him that, though her job didn’t require it.

Kelly-DiMeglio could see his determination. Each time she suggested a resource, he pursued it. But she knew that determination got many students only so far if they lacked someone on campus to support them. She tried to be that someone for him; he took her interest as proof that he mattered.

Shegog sought other guides, too. As a member of DCCC’s state-financed Act 101 program, which supports low-income and first-generation students, he was required to meet with Rose Kurtz six times a semester; he stopped by once a week. She was a counselor in Act 101 whose job was to serve the whole student, connecting advisees with resources, such as child care and places to get meals, whatever they needed.

Early on, Kurtz, a licensed professional counselor, helped Shegog understand that he couldn’t thrive in college if other aspects of his life were in disarray, advice he would later call essential. When he told Kurtz that Riley’s son and daughter were getting high in the house they all shared, she told him to get his house in order or else he would struggle. So he and Riley laid down new house rules.

Kurtz warned Shegog that working too many hours at Panera would hinder his studies. “Your life is education now,” she told him. Though he resented the advice at first, he came to see the wisdom in it. He cut back on his hours, as well as on AA meetings, which he had been attending four nights a week. He threw himself into studying, reading the Bible, going to therapy, and meditating — a recovery routine on his own terms. His commitment inspired Riley to enroll in a master’s program in health-care administration.

Shegog could tell Kurtz cared about him. In her tiny office, they celebrated his triumphs, like making the President’s List, with all A’s, in his second semester, and joining Phi Theta Kappa, an honor society for students at two-year colleges. She encouraged him to get enough rest and eat right. Found him a new therapist, one for Riley, too. Coached him on engaging with professors. Showed him how to apply for testing accommodations through DCCC’s office of disabilities. Helped him pick courses in which he was likely to succeed.

A foreign-language course was out of the question. Shegog, who had failed Spanish in high school, knew he would struggle to learn another tongue, and his GPA had to be stellar to get a full ride to a four-year college. But a worry burrowed into him: Could he even pass foreign-language courses down the line?

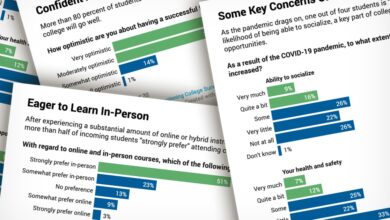

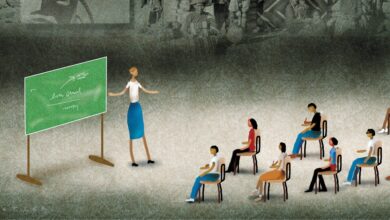

Relationships, a form of what sociologists call social capital, also matter a great deal. A growing body of research illuminates the importance of personal connections and networks, which are especially crucial for marginalized students, enabling those without financial resources and college know-how to benefit from people who have both. One recent study found that the components of grit did not predict first-generation students’ GPAs, though access to social capital with faculty and staff did. Another study traced the importance of existing and informal relationships among first-generation students seeking information and campus resources they needed to persist. Yes, ow hard you try in college is important, but so, too, is who you know.

At DCCC, Shegog, intense and gregarious, created his own support group almost instinctively. Each week he pinballed around the campus, becoming well known for his high-beam smile and infectious exuberance, for talking with students others ignored, for being a hugger who texted in all caps and seemed to speak in them, too.

The first person Shegog befriended at DCCC was Stephanie Moriarty, who worked in the campus-life office. He wandered in, looking lost and unsure in his green-and-yellow garb. Moriarty, a Wisconsin native, was a Packers fan, too, and after they chatted a bit she told him, “Come on back any time.” He returned often to study in a comfy chair in the corner; she let him use the microwave in the staff lounge to warm up his leftovers. He called her his “Green Bay mom,” seeking her advice on neckties, relationships, and his future.

Though Shegog wasn’t sure what he wanted to do with his life, he knew he loved public speaking, how he could move a roomful of strangers with words, which Riley had seen many times. Not long after they met, Riley drove him to the treatment center in Bensalem where he had spent 78 days. There she heard him give his first speech outside of AA, a raw, thunderous riff on pain and recovery, which got a standing ovation and left some people in tears. Later, Riley told him she had felt God when he spoke.

Emily Cohen for The Chronicle

After enrolling at DCCC, he kept speaking at rehab centers. At one talk, someone suggested that he start an LLC. Shegog had to Google it: a limited-liability corporation. Could he really start a speaking business?

Shegog was weighing the idea in summer 2018 when he and Riley visited Washington, D.C., to celebrate the second anniversary of his sobriety. At the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, he stared up at the towering granite statue of MLK. “I’ve cut out the bullshit,” he said. “I’m going to do right.” Then he and Riley came up with a name for his company: The Message LLC.

Weeks later, a close friend of Shegog’s died of a drug overdose at 39. Shegog, who had been his AA sponsor, spoke at the funeral wearing a charcoal suit, the only one he owned. His neighbors had bought it for him weeks earlier — a gesture of support for his plan to start a speaking business.

Shegog sometimes felt like getting loaded and smoking weed to dull the pain of losing his friend. Instead he lifted weights and devoured healthy food. Angry, he wanted to reach audiences beyond treatment centers, to tell college administrators how they could help students struggling with addiction.

That summer, Shegog attended a conference at Saint Joseph’s University. He met a writer there who connected him with an opinion editor at The Philadelphia Inquirer who was seeking someone to write about collegiate recovery programs. He emailed the editor his essay on identity from English 025. With some coaching, Shegog did some research and turned parts of his first remedial-English paper into an op-ed.

In August, the Inquirer published Shegog’s piece, which ran with his photograph. In 548 words he described students in recovery as “seasoned souls” who are especially dedicated to their studies. All community colleges, he wrote, should have on-campus recovery programs to support them: “I hope that one day soon, students will not have to fight for addiction and recovery services but that they will be as common as finding the bookstore.”

Shegog’s phone blew up. DCCC’s president invited him in for a meeting. She connected him with the marketing department, which would publish a front-page magazine article about him. An official in the advancement office told him he was the face of the college. There’s life in this paper.

After the op-ed, a technical school in New Jersey invited him to speak. When asked about his fee, he was flummoxed: “You’d pay me for that?” In the end, the school didn’t pay him for the talk, or reimburse him for the $200 he spent on Uber rides. But it did provide free food and coffee. From Panera.

Knowing he had much to learn about the speaking business, Shegog got to know Brieanne Rogers, then assistant director of campus life at DCCC, who booked speakers. She helped him draft his first contract and establish a speaking fee. She advised him on negotiating effectively and explained why he needed an elevator pitch. Though he was her elder, he called her his big sister.

One Sunday morning while Riley was making pancakes, Shegog pulled up the completed online form required to establish an LLC in Pennsylvania. As soon as he hit Enter, his business would become real. Did he really want to relive the worst of his past again and again for money?

“I can’t do this,” he told Riley.

She told him it would be wrong not to share his gift: “Stop fearing it. Let’s go!”

He pressed Enter.

Kurtz, the Act 101 counselor, knew that students often don’t succeed unless they feel connected to someone on their campus, and she wanted Shegog to have a positive male role model. So one day she walked him over to the office of Kendrick M. Mickens, director of student outreach and support.

Mickens, a Black man from North Philadelphia, remembered what it was like to be an undergraduate in need of guidance. While attending the predominantly white West Chester University in the late 1980s, two administrators saw promise in him that he hadn’t seen, inviting him to join committees and speak at campus events. And as a result, he would say later, he “just blossomed.”

At DCCC, Mickens tried to help others blossom, too. So after Shegog described his hopes of building his speaking business, Mickens wanted to get him on a stage. He called a contact who was organizing a student-leadership conference sponsored by the Pennsylvania Black Conference on Higher Education. He asked if a student could present there; yes, he was told, if the proposal looked good enough.

Shegog submitted a proposal for a session, which a conference organizer helped him refine. He lacked a curriculum vitae — required of presenters — so he typed up his achievements: the Inquirer op-ed, employee of the month at Panera. Though he used a large font, the text barely filled a half-page.

His proposal was accepted, but then the event’s organizers wavered. One called Mickens to say they typically didn’t have presenters who were still students. Mickens went to bat for Shegog, telling the organizers that he deserved a chance: You accepted his proposal. I don’t see what the problem is.

That did the trick. In October 2018, Shegog went to Harrisburg, Pa., and led a workshop (“Creating Healthy Lifestyles for Students in Recovery”). At the conference, Shegog met a student leader from Clarion University of Pennsylvania. The connection led to his first paid keynote speech the following winter. Riley came, and so did his mother. Afterward she proudly waived his $1,200 check in the air.

Shegog had always wanted to feel like he belonged in every room, but often he didn’t. In March 2019, he walked into an education conference in Philadelphia attended by administrators and faculty, knowing that he would be the only person there without even a bachelor’s degree. In the hotel lounge, with trays of hors d’oeuvres circling, people seemed to be speaking another language, discussing books he hadn’t read, articles they had published in journals he couldn’t afford.

Feeling dumb, Shegog called Kurtz and told her he didn’t belong there. She told him to walk into his session with his head up and speak from his heart. He tried. But during his talk he botched a statistic. Nothing flowed. Afterward, he felt terrible, sure that he had bombed on his biggest stage yet.

Thank you, Jesus, he thought.

Her name was Christine Morris. A few months earlier she had been an adjunct faculty member at nearby Montgomery County Community College, or MCCC, when one of her students had a mental-health crisis in her class. That week a diligent student who had been excelling in her course died from an overdose. Shaken, Morris asked herself: What are our students going through? What don’t I know?

Weeks later, she switched jobs, becoming coordinator of Act 101 at MCCC, the same program Shegog belonged to on his campus. After meeting at the conference in Philadelphia, he and Morris e-mailed often. He helped her better understand students’ challenges just as she was learning to help them cope day-to-day with problems that she previously hadn’t thought much about.

One day Morris called Shegog for advice on how to approach a conversation with a student who seemed to have a substance-abuse problem. Shegog advised her to start by saying that she cared about her.

Getting to know Morris helped Shegog, who, at her invitation, would give a handful of paid speeches at MCCC and join the college’s Act 101 board. But their friendship was a two-way street. Getting to know Shegog had changed her, deepening her understanding of poverty and homelessness, how easy it was to fall into both, because of addiction, mental illness, the lack of a safety net. “I wasn’t born to be homeless,” he often said. It was something that happened to him.

Shegog told Morris how much small kindnesses mattered to people who have nothing. He recalled how a woman working at a downtown Dunkin’ Donuts in 2016 would place boxes of unsold doughnuts on top of a Dumpster instead of inside of it, so homeless people could get to them easily. He had often filled his belly with those doughnuts.

Several months after meeting Shegog, Morris had dinner at a restaurant in Philadelphia. Driving home by herself, she was stopped at a red light when a young man holding a sign asking for food walked by her car. In the past she would’ve sat still and stared straight ahead. But just then Morris thought of Shegog. She rolled down her window, greeted the stranger, looked him in the eye, and handed him her box of leftovers. She saw how grateful he was. And she thought, That easily could’ve been one of my students.

He decided to enroll at West Chester University, which gave him a full-tuition scholarship and a spot in the honors college. Still, he was anxious about transitioning to a four-year campus during Covid. His professor for “Communication, Literacy, & Inquiry” found ways to foster connections among her students during a virtual semester. Elizabeth A. Munz, an associate professor of communication and media, started each class by asking students how they were doing, what they were up to, a relatively small gesture that Shegog loved. Those 10 minutes, she believed, helped instill a sense of community.

Emily Cohen for The Chronicle

Munz also adopted a new practice that fall: asking a handful of students to stick around after each class for an informal chat. Sometimes they disclosed financial hardships and other personal challenges that helped her understand what they were going through. Shegog often wondered why all professors didn’t do the same thing. He would later describe the importance of those interactions in a speech at West Chester. “Do you know how far it goes,” he said, “when you know that the person teaching you, cares about you?”

Improving pedagogy. Increasing retention. It all boiled down, he believed, to caring.

Shegog’s first semester at West Chester was tough. He took Spanish 101 because the university requires students seeking a bachelor of arts to pass two semesters of a language besides English. For him, this was a burden: He struggled to absorb new words, sounds, and sentence structures over Zoom. Many nights he stayed up late studying, eating dinner after midnight. But the lessons didn’t connect in his head. Struggling to grasp elementary Spanish sank his confidence. It made him angry, gave him stomachaches.

Knowing he had to maintain a high GPA for his scholarship, he withdrew from the class.

Sometimes Shegog felt ambivalent about higher education and its many requirements. He wanted a bachelor’s degree badly, but he was frustrated by how much stock people put in academic credentials. He winced when professors insisted that students call them “Dr.” Some conferences, he learned, wouldn’t invite speakers who lacked a master’s degree. At one conference he attended, a professor asked where he had earned his bachelor’s degree. When he said he didn’t have one yet, she asked, “What are you doing here?”

He was there because he had fought through what many scholars had merely studied. He was there because he had survived a substance-abuse epidemic that he believed many college officials ignored. In 2019, about one in seven young adults in the country needed treatment for substance use, according to one estimate. Approximately 600,000 college students, other research has found, describe themselves as in recovery from an alcohol and/or other drug use disorder.

Shegog’s professional ambitions had entwined with his academic goals. He kept studying hard, knowing that straight A’s led to scholarships (he had racked up more than a dozen), and scholarships led to dinners. Dinners helped him meet people, increasing his chances of speaking at events. All of that, he believed, helped him stay healthy: If he drank again, he would drop out of college, and a business built on sobriety would fold.

With just an associate degree, Shegog believed that his greatest assets were his voice and his story. Kelly-DiMeglio, his English professor at DCCC, had shown him that he could take the shame he felt about the past and reshape it. So he refined his speeches in the cold, musty basement, timing himself.

He liked rehearsing in the uncomfortable space, standing under a low ceiling, shouting, crying, and cussing while composing passages in his head. The plain white wall gave him nothing, helping him figure out what he wanted to say without worrying about an audience’s reaction.

Emily Cohen for The Chronicle

Shegog called public speaking “a bittersweet joy.” He decided early on that he would frankly describe some of his most difficult experiences, as hard as it was. Because those experiences had shaped him. Because they revealed truths about addiction.

The story of a once-homeless guy who made it to college and saw all his problems vanish while sauntering to prosperity? That wasn’t his story. Success didn’t heal wounds; A’s and B’s didn’t erase trauma. He still felt the pain he felt when a white woman spat on him as he was begging for change — “Get a job, nigger,” she said. But that pain was a gift: Whenever he thought about having just one drink, he summoned the memory, which extinguished all temptation.

While earning credits toward a communication-studies degree, Shegog was learning how to be a part of a family. He and Riley made plans to get married, and over the years he’s bonded with her daughter, Megan, whom he calls Mego. She was 20 when his op-ed was published in the Inquirer. Staring at the newspaper in his hands, she exclaimed, “That’s dope.”

Her words kept him going when he felt stuck in between two worlds. Last summer, Shegog flew south on Louisiana State University’s dime after the Shreveport campus had invited him to speak at freshman convocation. He felt like a king driving a rented Chevy Spark with the window down, knowing he was about to give two paid speeches. But a few days later he was clearing customers’ trays at Panera, a job he kept, in part, to continue receiving state-provided health insurance covering the costs of meds and weekly therapy essential to his recovery.

Shegog had climbed high up into a new life, but he still felt close to the bottom.

When he got a D on his first test in a biology course at DCCC, he befriended a high-achieving classmate, partnered with her in groups, and often picked her brain. He finished with an A in the course.

Before each semester, Shegog emailed his professors to introduce himself, describing his “hunger to learn,” asking if there were any additional readings he could do. He stopped by their office hours even if he didn’t need help. He often went to the tutoring center to get feedback on drafts of papers. In class, he noticed who was taking notes and asking questions, and then traded phone numbers with them. He finished homework assignments in advance.

Though Shegog had liked most of his professors at West Chester, at 38 he often felt out of place among younger students, most of whom were white. Many were living at home, experiencing their first breakups. He sometimes smelled weed on his classmates’ clothes, and heard professors joke with students about partying hard. He often held his tongue during his “Drugs and Society” class, where homework felt like reading about his life. One day a classmate posed a question: Was alcoholism a choice? Yes, another student said, a choice to drink instead of working hard. Finally, Shegog raised his hand and explained that alcoholism is a disease.

West Chester, though, had helped him raise his game and ambitions. He wanted to get a master’s degree, then a doctorate, because he wanted to get into rooms where policy making happens, to advocate for low-income and underrepresented families, people afflicted with addiction. And he wanted to grow his business and earning potential.

But Shegog still had to earn six foreign-language credits. Last fall, he took another virtual Spanish 101 course. Once again he struggled. Once again he withdrew.

His speeches often turned strangers into friends, and evidence of that fact hung on his living-room wall: It was a wooden sign emblazoned with “The Message LLC,” a homemade gift from a student at Kutztown University who had heard him give a virtual speech last winter. After reaching out online, she confided that she was depressed and struggling with an eating disorder. She also told him that she had a high GPA — a reminder that the standard gauges of How Students Are Doing reveal only so much.

Shegog straightened his tie while stepping around his burly mutt named Gemma. He called upstairs to Riley: “We ready?”

Inside their black Nissan Rogue, the couple held hands and prayed. Later, while driving up I-476 North, Shegog riffed on one of his major concerns: College officials who underestimated the prevalence of addiction. He described a recent chat with an administrator at a nearby private college who insisted that his campus didn’t have a substance-abuse problem. “That,” Shegog said, shaking his head, “is deee-niii-alll.”

After pulling into a parking lot at MCCC, Shegog took a picture of the “Reserved” sign on the orange cone marking his spot. Inside the airy Health Sciences Center, he greeted strangers in his usual way: “God is good! Woke up breathing!” He scanned the podium and rows of empty chairs in an open area by the gym: At 9:47, hardly anyone was there. Fidgeting, he joked with Riley about giving his speech to just one student.

But a few dozen people showed up, and his friend Christine Morris, MCCC’s Act 101 coordinator, warmly introduced him. Leaving the podium to stand in the audience, he fist-bumped late-arriving students. “How y’all doing? Come on in. Bless you.”

These days Shegog felt powerful when he spoke, the way he had felt in high school when, after years of being bullied, he first strapped on quad drums and marched with the marching band. At MCCC, his voice snapped a few spectators’ heads back. He got loud, then spoke softly, scowling and smiling and looking students in the eye.

Shegog, who has bipolar disorder, described his routine for staying healthy, the importance of the Zoloft tablet he takes each day. It was his way of confronting the stigma associated with mental-health challenges. He related his story to what students might be dealing with. “If there’s one thing about all of us that connects us, we’ve all been through pain of some sort.”

Montgomery County Community College

Whether the pain related to alcoholism, depression, or Covid, he told them, they could confront it, carry on, thrive. “There are places that will help you — tap into ’em. You have no shame, and there is nothing to be afraid of. You’re human.”

Shegog riffed on the importance of connection in college, urging students to stop being in awe of their professors and get to know them. He urged professors to do the same, and to share potential opportunities, such as conferences, with their students.

Though Shegog had some well-worn lines (“Health is wealth”; “You’re not a mistake”), he wasn’t a typical motivational speaker. He was an entertainer, a self-deprecating storyteller, a fire hose of emotion. Though much older than most of the students, he was one of them, with a take-home test for COMM 215 due that night.

For 45 minutes, no one — not the young woman in the pink fuzzy slippers, or her friend in the leopard-print mask, or the young man in the 76ers hoodie — glanced at their phone. “You’re somebody,” Shegog said. “What you’ve been through matters.”

Afterward, nearly a dozen students lined up to chat with Shegog, exchange contact info, and pose for selfies. A young woman with long red hair clasped both of his hands and prayed with him. A graying woman just out of prison asked for advice. A baby-faced young man with a heavy backpack sought tips on breaking free from bad influences.

After chatting for a while, they shook hands. “Let me know,” Shegog said, “if you need a recommendation letter, OK?”

It was a daily grind. Studying hard was just one part. Recovery was forever. It required obedience, his mother had told him. He remained devoted to therapy, journaling, meditating, and yoga, and meds. Each day he popped an elderberry tablet, too.

But as good as “God and grind” sounded, faith and determination didn’t explain it all. His ever-growing cast of mentors and supporters, which he called his “Freddie Village,” helped him navigate college, buoying him when doubt struck, and calling him out when he needed it. Many students lacked a village, which was why he offered to write a recommendation for the young man at MCCC. It was why he mentored a handful of younger students. Go to professors’ office hours, he told them. Get to know three administrators each semester — they hold keys to opportunities.

Students in recovery, Shegog wrote in his Inquirer op-ed, “tend to look up to the people others look down on, because they know pain and struggle.” His mentees included a young man from a wealthy family attending Rosemont College, and a formerly homeless man who enrolled at Pennsylvania State University at Brandywine after serving time in prison. They had grappled with addiction, psychological problems, self-doubt, or loneliness — something. Shegog believed breaking bread with his mentees was an important way of showing them love, so he treated them to meals at his favorite Italian place.

He often checked in with Jaron Felder, a senior at West Chester whom he had met when they were both students at DCCC. They talked about their experiences as Black men on a predominantly white campus. The friendship had helped Felder stay grounded, hopeful, motivated. Having guides who can share their perspectives on life was crucial, he had learned: When weighing tough questions, you needed thoughts in your head besides your own. And you needed better advice than “Listen to your heart,” because, as Felder put it, “your heart can be deceptive.”

As Shegog mentored others this fall, he leaned on guides of his own, including Sara Goldrick-Rab, a professor of sociology and medicine at Temple University. They had met when she spoke at DCCC in 2019, asking professors in the audience what they would do if a student had missed three straight classes: Email them the attendance policy, or ask them if they were OK? When Goldrick-Rab said they should do the latter, Shegog felt like she was a kindred spirit. After her talk, he put a hand on her shoulder and introduced himself.

Goldrick-Rab, president and founder of the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, helped start #RealCollege, a national movement to support students’ basic needs, such as affordable food, housing, and transportation. She believes many professors and administrators have a lot of power — resources, social networks — that they could share with students but often don’t.

Emily Cohen for The Chronicle

So when Shegog asked her for mentorship, she obliged. Before long he was in Houston moderating a session at a national conference sponsored by the Hope Center. Goldrick-Rab walked around with him, introducing him to many people. Months later, he applied for a spot on the center’s Student Leadership Advisory Council and got one. The group was full of students whose challenges reminded him of his own. They often shared advice, as well as their own networks, with each other. Last March, Shegog spoke at a #RealCollege webinar, after which speaking invitations poured into his website.

This fall, Shegog gave a speech at the National Institute for Staff and Organizational Development’s virtual conference, which had invited Goldrick-Rab to speak in 2020. The organization, which supports community and technical colleges, told him that it had never had a student give a keynote, but that a speaker of his caliber warranted an invitation.

That night Shegog and Riley went out to dinner, where he clinked his fruit-juice mocktail against her Shirley Temple. By then he was thinking ahead to November 21, a day he had long looked forward to, a day when he would feel that he truly belonged in higher ed. Or so he thought.

Shegog had a heavy heart that afternoon. Riley had learned that her 29-year-old niece had just died from a drug overdose. A few weeks earlier, Shegog had spoken at the funeral of a friend’s teenage daughter who had died from the same cause. Both losses reminded him why it was crucial to speak about the ravages of addiction.

Inside the Philips Autograph Library, Shegog surveyed the Gothic windows, wood-paneled walls, and glassed-in bookshelves — a sanctum built for an exclusive ceremony. He wore the tailored brown-plaid suit he had bought just before his 39th birthday two weeks earlier. “Nice suit,” said a young woman who was also being inducted that afternoon. She asked him if he worked for the university.

After taking a seat in the second row, Shegog saw maybe 60 people in the room but not one Black face. Once again he felt uncomfortable, out of place. The room was whisper-quiet and dark; the mood, serious. Like a mob induction, he thought.

Kevin W. Dean, director of the honors college, stood at a lectern. He told the audience that there were 14,000 students on the campus but just 22 were about to join Omicron Delta Kappa. After he called the first inductee’s name, she walked up to a table topped with a vase of flowers, signed her name in a book, and then faced the audience as Dean rattled off her many achievements.

Shegog realized that the ceremony he had long anticipated would mostly involve each inductee’s CV being read aloud. This is crazy, he thought as tallies of community-service hours and leadership positions kept coming.

Still, when his name was about to be called, happiness overcame him. Five-and-half years ago, he was lying on a sidewalk hoping to die; now he was sitting in a gorgeous room under a ceiling of ornate molding. “Look how far we’ve come,” he texted Riley, seated nearby. All his life he had thought he wasn’t smart enough. But the truth had sunk in: He was intelligent, a worthy student with a 3.8 GPA.

“Frederick Shegog … summa cum laude.”

After the ceremony, Shegog posed for photos with two guests: Kurtz, the counselor from DCCC who still guided him, and Rogers, who had helped him start his business. He carried home a certificate. “In recognition of conspicuous attainments,” it said. His name was printed in bold script.

But that certificate obscured a truth, just like all the documents conferred upon students do: No one succeeds alone.

But imagine if the official documents commemorating success in college included other names, too. The names of people who had done something to help that student succeed, who had gone out of their way. Mothers and fathers. Grandparents and guardians. Significant others and friends. Professors and staff members and tutors and ministers and mentors of all kinds. The cast would vary from student to student.

In a world with such a tradition, Shegog’s Omicron Delta Kappa certificate would’ve been imprinted with dozens of names. Kim Riley’s. His mother’s. The names of all the members of his Freddie Village. And wouldn’t it have also included the names, in fine print, of policy makers behind the state-financed student-support programs that had enabled him to afford college, giving him a chance to meet so many helpful people? People without whom, he was certain, he wouldn’t have made it, no matter how hard he tried? He had persisted, in part, because many faculty and staff members had done their jobs well, and, often, much more than required.

Pull yourself up by your bootstraps. Roll up your sleeves. Buckle down, kid. Shegog had heard all those maxims, rooted so deeply in American mythology that one could mistake them for practical advice. But experience had taught him that those adages were empty.

They were also dangerous: The more we believe that a student’s success is theirs alone, the easier it is to believe that no one else is responsible for a student’s failure.

Talent was good to have, but Shegog had learned that someone had to show you how to use it. Applying for scholarships was important, but someone had to tell you about them first. Knocking on doors? Impossible if you didn’t know the doors were even there.

Success, in college and in life, had a shape. It was a circle, the wider and more devoted to you, the better. He understood that many privileged students arrived at college with a circle around them; he had to build his own.

Shegog left the ceremony wondering how many talented students who looked like him ended up failing just because they lacked the supporters they needed. Though grateful to belong to Omicron Delta Kappa, he went home feeling conflicted. He tucked the certificate under some books and forgot it.

A week later, Shegog walked into a venue he once thought he would never see: Lambeau Field. Wearing the hat and scarf one of his Panera moms made for him years ago, he cheered the Packers to victory. The tickets were a gift from his Green Bay mom.

In December, Shegog got his fall grades: All A’s. He was on track to graduate in May, when Riley would get her master’s degree. And he planned to start a master’s program in public administration at West Chester this fall.

But then, just before Christmas, his plans seemed to unravel. Because of Spanish.

No way, he thought.

The fall semester had drained him. He needed time with Riley, time for himself. He feared the toll that the course would take while he was trying to be a supportive husband, son, and mentor. Riley’s daughter, Megan, almost a year into recovery, often sought his advice. What if she called when he was in class? He weighed his commitment to his own recovery, too. “Every day I wake up, I got one job — stay healthy,” he said in his speech at MCCC. “There ain’t no days off.”

Emily Cohen for The Chronicle

But if he didn’t pass Spanish 101 this winter, he couldn’t take Spanish 102 this spring — and couldn’t finish his bachelor’s degree in May. Wary of an accelerated summer course, he would have to take Spanish 102 next fall, which would mean delaying graduate school. At 39, he already saw himself as behind in life.

Shegog felt embarrassed, like he had screwed up. Years ago he would’ve doused his frustration with brandy and weed; that night he ate some ice cream. His Freddie Village rallied around him. Bonnie Kaplan, a retired school teacher and one of his Panera moms, texted support: “You should never be embarrassed when you make choices that are necessary for your well-being. … You are loved, and I remain proud of you. The only Spanish you need right now is no problemo.”

Later, Shegog learned that he could still participate in commencement with his foreign-language requirement as yet unfulfilled. But he hated the thought of walking across the stage with a worry looming over him: Could he even pass Spanish 102?

Shegog wasn’t sure. Slogging through Spanish 101 this winter, he found it draining to keep up, relying on a tutor, on Riley, and on prayer to stay above a C. So at the beginning of the semester he emailed several professors, asking for help.

In February, Shegog met with his new academic adviser, the chair of the communication and media department, who told him something that no one else, including his previous adviser, had ever mentioned: Students could request permission to use a “non-approved course” to fulfill a graduation requirement, an academic swap that the university sometimes allows due to extenuating circumstances. It was a way to meet students where they’re at while maintaining the integrity of a requirement.

But a student could only make such a request if they knew about the process, which is mentioned but not fully explained in the university’s 2021-22 Catalog. The required form was online, in a place Shegog hadn’t known to look. To him, it felt hidden.

Shegog emailed Israel Sanz-Sánchez, assistant chair of the department of languages and culture, explaining how despite his high GPA he had struggled to pass Spanish courses. The foreign-language requirement, Shegog wrote, was “causing a heavy burden that can delay my educational journey.”

To fulfill West Chester’s language and culture requirement, Shegog had to pass two language courses and three related culture courses. He asked if he could substitute an additional culture course, which he would take this summer, for Spanish 102.

A few days later, Shegog met with Sanz-Sánchez, a professor of languages, to make his case. He had prepared as if he were about to negotiate a speaking contract. He wasn’t trying to be lazy, he told the professor, but Spanish 102 was an obstacle standing between him and his goals.

Sanz-Sánchez, who had examined Shegog’s record, could see that he was a dedicated student who had tried to fulfill the requirement in the usual way. The professor understood that providing a different way to meet that requirement would benefit him. So he told Shegog he would support his official request for a course substitution, which he later forwarded to an associate provost for academic affairs, who would either approve or deny it. Not all requests, Shegog knew, were successful.

The requirement that had long vexed him existed for a reason: Proficiency in other languages and cultures is widely considered an important aspect of an undergraduate education. But Shegog believed he deserved a ticket out of Spanish 102. He had challenges other students lacked. And one could say he had mastered many languages. The language of college, for one. The languages of recovery and poverty, of resourcefulness and connectedness.

While waiting for an answer, Shegog reflected on his college experience. He felt the truth in something W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in 1903: “Education must not simply teach work — it must teach Life.” Those words had moved Shegog when he stumbled upon them in 2018. He came to college seeking a new life, and many people he met there showed him how to live it. College gave him a vast network and made him think hard about what one person owes another, even a stranger.

Being a student had given him a reason to stay healthy, helped him thrive in a loving relationship and be the kind of father he hadn’t known himself. Megan, who wasn’t in touch with her biological father, calls Shegog “Dad”; this fall she gave him a small plaque that said, “You may not have given me life, but you sure have made my life better.” Inspired by his success, she was making a second go at college, enrolling at DCCC.

Shegog had received several awards, but none meant as much as his mother’s praise. She had told him she was proud of who he had become, grateful that he was a family man: “You have broken a cycle.”

After 10 days of waiting, Shegog got an email: His request to substitute another course for Spanish 102 had been approved. He whooped triumphantly. “I got it! I got it! I got it!” For years he felt like he had been carrying a sledgehammer over his shoulder, and just like that, it vanished.

That night he texted the latest to many members of his Freddie Village. One by one they texted back to celebrate his good news.

It was theirs, too.

[ad_2]

Source link