In Fight Against Ableism, Disabled Students Build Centers of Their Own

[ad_1]

In addition to clearing those hurdles, Sullivan longed for a community that could relate to her struggles. She soon connected with another student, Emmett Lockwood, who had already been working on a proposal for a disability cultural center, where disabled students could build a sense of community and culture.

Thanks to student advocates, including Sullivan and Lockwood, the University of Wisconsin at Madison recently became the latest in a growing number of colleges with disability cultural centers, which aim to shine light on the perspectives and experiences of disabled people, foster a sense of community, and promote activism and disability justice. Altogether, at least 12 disability cultural centers now exist nationwide; in addition, students are working to create new centers on about a dozen other college campuses.

Sullivan said that the creation of a space on campus specifically for disabled students was “sacred” to her. “Within this coalition of students, there’s this understanding of, yeah, we all have different disabilities and different experiences, but we have this common objective of dismantling ableism and, you know, making higher education something that’s safe for everyone,” she said.

Last week, the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Disability Cultural Center hosted the largest gathering to date of such centers for a two-day, virtual symposium, where advocates discussed how and why the centers were created, the importance of disability culture, and the impact of the centers.

At many colleges with disability cultural centers, it took years of advocacy to create the centers at all. Once established, the centers provide programming for students, and sometimes faculty and staff, to learn about disability as a social-justice issue and a lived experience and to provide a safe space for disabled students to socialize. Diane Wiener, who served as the founding director of the Syracuse University Disability Cultural Center, said she felt the symposium was historic and would have ripple effects for years.

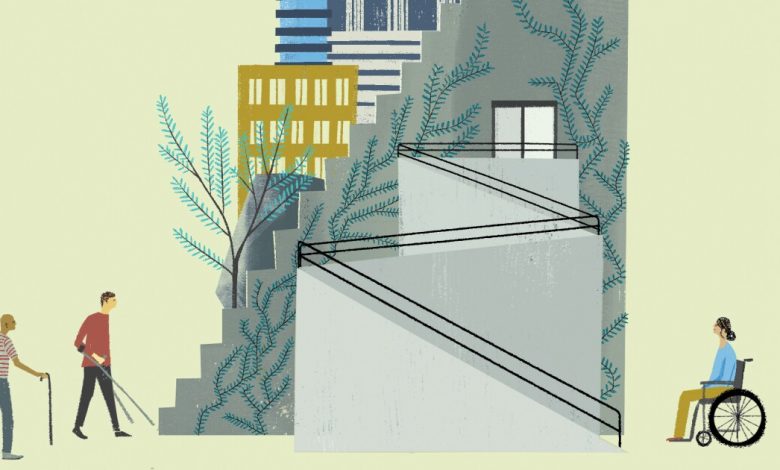

Disability cultural centers are intended to honor and celebrate disability culture, much as students of color have done through cultural centers centered around race or ethnicity. In contrast, disability resource or services centers, which are much more common at colleges, are typically focused on legally required accommodations for individual students.

UIC DCC

The cultural centers vary across campuses. At some colleges, for example, disability cultural centers are housed within disability resource centers, while at others, they are separate. Cultural centers typically bring speakers to campus to discuss ableism and disability justice, host social events, and provide resources for disabled students. Syracuse University’s Disability Cultural Center, for example, hosts an annual event with inclusive and adaptive sports and health and wellness programs including adaptive bikes, a climbing wall, and pet therapy.

A recurring theme for UIC’s symposium, which took place during Disability Pride Month, was the desire for disability cultural centers to go beyond legal requirements to help students find a sense of self and belonging. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that one in four American adults have some type of disability, but several speakers at the symposium talked about discovering disability as an identity only during college.

Students at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities established the nation’s first cultural center for disabled students shortly after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. It would take about a decade for the nation’s second and third disability cultural centers, at Syracuse University and the University of Washington, to be founded. But since 2016, at least eight new centers have appeared on college campuses, in many cases after years of student advocacy.

Margaret Fink, the director of the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Disability Cultural Center, said that having a generation of disabled students who have gone through school after the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the rise of the internet and social media, and more recently, the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, have all contributed to the recent groundswell of activism around disability culture. The pandemic, for example, showed many people that it is possible to make higher education more accessible to many more people through remote lectures, prompting some students with disabilities to ask why some colleges are ending the hybrid learning some found so helpful. And as more people are diagnosed with long Covid, Fink said, there will be more students identifying as disabled, for as long as they continue to show symptoms.

Toni Saia, an assistant professor in the department of administration, rehabilitation, and postsecondary education at San Diego State University, wrote her doctoral dissertation on the role of disability cultural centers from the perspective of disabled students involved with the center. There’s very little research on disability cultural centers.

Saia said the students she interviewed at the University of Arizona, where she was serving as the first program coordinator for the Disability Cultural Center while attending graduate school, saw a clear disconnect between the way their institution and the disability cultural center on campus viewed disability. Students said that the institution viewed disability through an individual accommodation framework, Saia said, while the cultural center viewed disability as an identity and something to be embraced and celebrated. Saia said the difference was particularly notable because the center had only been open for a few months when she conducted her interviews with students.

“Access is one part, but do we feel welcomed and valued?” Saia said in an interview. “If there are so many physical and/or attitudinal barriers to a person’s participation, it makes it difficult for higher education to be a place where you can embrace your identity and culture.”

For some, disability cultural centers offer a chance to reframe the narrative around disability. Sullivan, for example, from the University of Wisconsin at Madison, said that disability is often framed as a problem, rather than an important part of identity and existence.

“I think that disabled and chronically ill people should be able to exist without being told that they need to conform and that they need to be fixed,” she said.

[ad_2]

Source link