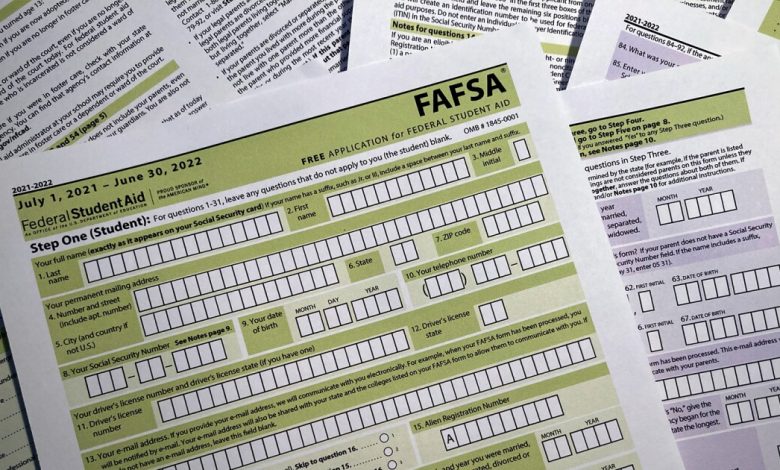

FAFSA Requirements Aim to Boost College Enrollments. Here’s Their Impact So Far.

[ad_1]

Last year, nearly half of high-school graduates from the Class of 2021 failed to complete a Free Application for Federal Student Aid. That means that altogether, millions of students left about $3.75 billion in federal Pell Grants unclaimed, according to an estimate by the National College Attainment Network, on top of other need-based aid they could have applied for through the form.

Now, a growing number of states are requiring high-school students to complete FAFSAs in order to graduate. The states hope to both help students take advantage of unclaimed financial aid and nudge some who otherwise may not have considered college to enroll — a goal that’s become more urgent since the Covid-19 pandemic has depressed both college enrollments and FAFSA completions.

“We’re trying to increase universal awareness of financial aid because that knowledge can shape [students’] college-going decisions,” said Bill DeBaun, senior director of data and strategic initiatives at the National College Attainment Network, which has long worked to increase FAFSA completions.

Kenya Fields knows just what DeBaun is talking about. Fields, a school counselor in Terrebonne Parish, La. — the first state to impose the graduation requirement, in 2017-18 — recalls one former student with exceptional grades and very good ACT scores, whose parents were commercial fishermen. He had grown up planning to enter the family business, but after completing the FAFSA realized he was eligible for Pell Grants and decided to study engineering in college. Completing the application “kind of opens up a new avenue, a new door,” said Fields.

Unsurprisingly, FAFSA completion rates have grown in the states with the graduation requirement. But while completions are strongly correlated with postsecondary enrollment, particularly for students from lower-income households, it remains to be seen whether the rules will improve college enrollment. Some experts caution that it will take a lot more than filling out a form to get more students to enroll in — and eventually graduate from — college.

States don’t seem to be waiting for evidence to act, however. Illinois followed Louisiana by imposing the requirement in 2020-21; Alabama and Texas are implementing it for the first time this school year; and New Hampshire’s requirement will take effect in 2023-24. (All of those states have opt-out provisions.) More than a dozen states have considered similar bills during the current legislative session, according to the Education Commission of the States.

Nebraska’s Gov. Pete Ricketts in 2020 vetoed a bill that would have required students to complete a FAFSA to graduate, calling it an unfunded and burdensome mandate on students and families not related to the core education mission of K-12 schools, among other reasons. Several states have shied away from mandates in favor of grants and other incentives.

A Tough Sell

There are many reasons why students and families hesitate to complete FAFSAs, despite the potential benefits. The complex form can be intimidating, particularly to students whose parents have not attended college, although there are efforts underway to simplify the FAFSA and its dreaded offshoot, verification, in which applicants are asked to submit additional information for further review. Many high schools don’t have enough counselors to help students think about their post-high-school careers and guide them through the process of completing a FAFSA. Some students’ parents are undocumented and wary of interacting with the government. And some families assume incorrectly that they earn too much to benefit from financial aid.

Fields said conversations with families can be awkward, covering personal issues, including how much cash a family has in the bank, how much a parent receives in child support, and when parents were married, separated, or divorced. It can take a lot of work to persuade some families to complete a FAFSA, particularly for students who are not already on a college track, she said.

For more-reluctant students, Fields likes to emphasize that FAFSAs can pave the way for financial aid to help with all kinds of postsecondary education, including technical programs. Students who want to become massage therapists, carpenters, or diesel mechanics, she tells families, can all benefit from additional education beyond high school.

So far, the mandates do appear to be increasing FAFSA completion rates. In the first year of implementation in Louisiana, FAFSA completion for high-school seniors grew by 26 percent. Texas and Alabama are currently leading the country in terms of year-over-year increases in FAFSA completions.

But if the ultimate aim of the policies is to help more students receive financial aid and enroll in college, researchers caution that more data is needed. Ellie Bruecker, a senior research associate at the Seldin/Haring-Smith Foundation, which works for college access and openness, studied the Louisiana FAFSA policy as part of her Ph.D. dissertation. She found that in the first two years of implementation, schools that had improved FAFSA completion rates the most saw an increase in college-going of less than one percentage point, primarily driven by schools serving the lowest numbers of African American and low-income students. “I would not call this a success at improving college enrollment at this point,” Bruecker said.

Bruecker said that she was not surprised that the impact on college enrollment was so modest. “I think the idea behind mandatory FAFSA is we want students to decide whether or not to go to college, but if you just fill out the FAFSA alone, that doesn’t tell you whether college is affordable for you,” Bruecker said. Filling out the forms does not provide any information about institutional aid students might be eligible for, for example.

While Bruecker does not oppose mandatory FAFSA policies, and acknowledges their impact might grow over time, she would rather see lawmakers spend limited resources on things like increasing the number of counselors in high schools.

Similarly, Peter Granville, a senior policy associate who has studied mandatory FAFSA policies at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank, urges states to think about what else they need to do to support schools and students through the FAFSA completion process. He cited Louisiana, which sends trained staff members across the state to instruct school counselors and work with students and families in hands-on workshops to help complete FAFSAs. States could also publicize new FAFSA requirements to take some of the burden off schools or direct additional funds to high schools to support FAFSA completion efforts.

Early Implementation

In Louisiana, Fields said she is thankful for the support the state has provided. That help was particularly vital after Hurricane Ida devastated the region last August, which shut down Fields’s school, South Terrebonne High School, for several weeks and forced some families to move into trailers and tents. Many of them lost the income tax records needed to complete the forms. About a quarter of the school’s 200 seniors have not returned since the hurricane.

Despite the disruption, South Terrebonne has among the highest FAFSA completion rates in the region. Fields laid the groundwork last year by visiting 11th-grade classes to start to build rapport with students and teachers. Last fall, she held numerous financial aid workshops, frequently partnering with the Louisiana Department of Education and two local colleges, Nicholls State University and Fletcher Technical Community College, to encourage and help students and parents to complete FAFSAs.

In Alabama, which is in its first year of implementation, Chandra Scott, executive director of Alabama Possible, which works to break down barriers to prosperity, said that the mandatory FAFSA policy is just one of many strategies the state is using to increase the number of students entering postsecondary education, with the ultimate goal of meeting the needs of the state’s work force. But she said the requirement has already had an impact in its first year.

“What this policy has done is elevated it for parents,” Scott said. “Every high-school mother or father looks over that graduation checklist — they want to make sure their student is checking off every tick box. That’s the difference here; it has brought awareness to the families. I feel it’s changing narratives in homes.”

[ad_2]

Source link