International Enrollments Tumble Below One Million for the First Time in Years, and Covid Is to Blame

[ad_1]

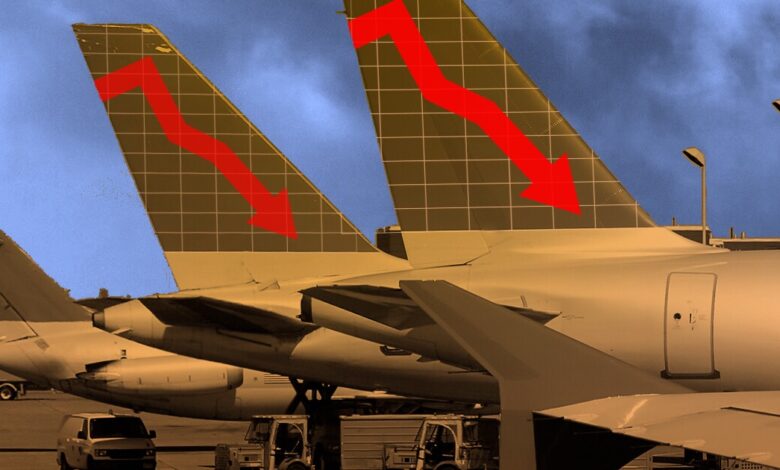

The number of international students at American colleges declined precipitously during the Covid-19 pandemic, with new enrollments tumbling 46 percent in fall 2020, a steeper decline than for any other student group.

The overall number of international students enrolled in U.S. higher education fell below one million for the first time since the 2014 academic year, according to the annual Open Doors report from the Institute of International Education and the U.S. Department of State. In total, some 914,000 studied at an American college last year, a figure that includes those who studied remotely from their home countries.

A preliminary snapshot, however, shows rebounding enrollments this fall. Colleges reported a 68-percent jump in new international students this semester, with the total number of foreign students increasing by 4 percent, according to a survey conducted by the institute, which is known as IIE, and nine other higher-ed organizations.

Still, the data, along with a Chronicle analysis of real-time student-visa issuances, suggest certain international enrollments may be quicker to bounce back than others. Those divides break in many ways, by academic level, by institutional type, and by students’ home country.

The pandemic’s disruption to global student mobility is without precedent. With international borders closed, total foreign enrollments dropped 15 percent in 2020, the largest annual decline in the 72 years IIE has published its annual international-student census. By contrast, international-student numbers fell cumulatively by less than 4 percent in the years following the September 11 terror attacks.

The financial fallout has also been huge — international students, particularly at the undergraduate level, typically pay full tuition, and their presence helps buoy both campus bottom lines and college–town economies. NAFSA: Association of International Educators released economic-impact data on Monday showing the biggest single-year drop in contributions by international students to the American economy, falling 27 percent, to $28.4 billion, in 2020.

Mirka Martel, head of research for IIE, noted that last year’s declines were largely driven by new enrollments and that colleges had mostly retained their continuing international students. That’s in part because the travel restrictions and health concerns that prevented new students from coming to the United States also kept many current students from returning home. IIE found that 80 percent of international students remained in the country last fall.

The pandemic spurred IIE to expand its definition of “international student” to include those studying remotely, whether in the United States or abroad. In previous years, the data only included student-visa holders in the United States.

Because of the different behavior of new and continuing students, academic programs that enroll students for multiple years proved more resistant to significant enrollment contractions during the pandemic than did shorter programs. Total doctoral enrollments dipped only slightly, by 3 percent, while the number of international students at the bachelor’s level fell by 13 percent in fall 2020.

But enrollments in associate and master’s degree programs each sank by 21 percent. Enyu Zhou, a senior analyst at the Council of Graduate Schools, said her organization’s research found that first-time master’s students were more likely than doctoral students to defer admission last fall rather than begin their studies online.

And the number of students in non-degree and English-language programs — which often last just weeks or months and have more-constant student churn — plummeted by 64 percent.

Participation in Optional Practical Training, the popular post-graduate work program, also declined, by 9 percent. Martel said graduates deciding to return home during the pandemic contributed to the falloff, but she also attributed the decreases to smaller incoming classes of international students even prior to the Covid outbreak. (OPT numbers are included in international-student totals because participants remain on student visas.)

Cheryl Delk-Le Good, executive director of EnglishUSA, an association of English-language programs, said many of her hard-hit members are starting to see students return. But a rebound could bring its own set of problems because intensive English programs, which are typically supported by student fees, lost many instructors to layoffs and downsizing during the pandemic. Hiring back may not be easy when “so many folks left the field,” Delk-Le Good said. “Anything more than a trickle could cause staffing issues for our programs.”

The variation in declines between academic programs was reflected in the pandemic’s impact by institutional type. Doctoral universities and baccalaureate colleges lost 13 and 14 percent of their international enrollments respectively. At associate’s colleges and master’s colleges and universities, the number of international students shrunk by a quarter.

A key question is how quickly the worst-hit institutions can regain lost ground. Although 70 percent of the 860 colleges that responded to the snapshot survey said they had more international students this fall, 10 percent remained at fall-2020 levels, and 20 percent reported a further decrease. The institutions in the survey account for about 60 percent of all international enrollments.

The snapshot survey does not break out this fall’s enrollment trends by institutional type or by degree level. But initial fall-enrollment data collected by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center show that while international graduate enrollments have rebounded, increasing by 13 percent, the number of international undergraduates has continued to fall, although less sharply than a year ago.

Since fall 2019, international undergraduate enrollments dropped by 21 percent, the clearinghouse reports.

International-education experts said there could be several explanations for differing trend lines. Graduate students are older and more likely to make their decision to study abroad independently. Parents, who play a major role in the plans of international undergraduates, may be more worried about sending their children far away in the pandemic’s wake.

The large number of deferrals among master’s students also meant there was a population of students ready and waiting to come to America, said Janet Gao, a research and program associate at the Council of Graduate Schools.

In addition, Covid-19 battered economies, knocking many people around the globe out of the middle class, said Rajika Bhandari, a higher-ed consultant who used to be the main author of the Open Doors report. That could disproportionately affect international undergraduates, eight in 10 of whom rely on personal or family funds as the primary source of support for their education. By contrast, only half of foreign graduate students pay for their degree out of their own pocket, and at the doctoral level, students are often supported by stipends and fellowships paid by American universities.

State Department visa-issuance data provides another window into this fall’s enrollment outlook. This spring, after the Biden administration lifted Covid-related travel restrictions for international students, U.S. consulates around the world prioritized the issuance of student visas.

Between May and August, the most critical months for fall enrollments, nearly 276,000 student visas were approved, 20,000 more than during the same period in 2019, a Chronicle analysis shows

Should that number be even higher? After all, this year’s visa applicants include those who deferred or studied remotely last year as well as a fresh crop of students.

IIE’s Martel said it was difficult to disaggregate the fall snapshot data to determine how much of the enrollment growth represents pent-up demand, but she noted that some 40,000 international students deferred admission last year.

The visa figures suggest an unevenness in the rebound from country to country. In China, the largest source of international students on American campuses, it seems like business as usual. The number of student visas approved there over the summer, about 87,000, was actually slightly ahead of pre-pandemic rates.

Yet in Saudi Arabia, which before Covid ranked fourth among sending countries, student-visa issuances between May and August were only at 40 percent of 2019 levels.

And the U.S. government has approved visas for 65,000 Indian students through the end of September — 20,000 more than it issued there in all of 2019, with three months still left to go in the year.

India has historically been a distant second to China in the number of students it sends to the United States, but that could be shifting as more Indian students embrace a foreign degree as a route to employability in a tight job market, said Ragh Singh, program manager for strategic global initiatives at Northern Arizona University. American colleges may also be benefitting because other popular destination countries, like Australia and New Zealand, have been slower to lift travel restrictions on international students, he said.

As colleges enter a third international-admissions cycle colored by the pandemic, there are many unknowns. But Martel pointed to a sign that suggests colleges are prioritizing attracting international students back to the United States — three-quarters of institutions in the fall snapshot survey said financial support for their overseas recruitment efforts was the same or higher than in previous years.

[ad_2]

Source link