Johns Hopkins U. Paused Its Plans for a Campus Police Force. 2 Years Later, Resistance Is Stronger Than Ever.

[ad_1]

As people shuffled into Shriver Hall on Thursday, Johns Hopkins University staff members in matching blue polo shirts handed out thick stacks of materials on the Baltimore institution’s plans for a private police force: discussion questions, PowerPoint slides, a copy of the law permitting Hopkins to mobilize a force, and the draft memorandum of understanding between the university and Baltimore police.

Fifty-one pages in all. Most double-sided.

But those who sought to have a meaningful discussion about campus policing would not find it here.

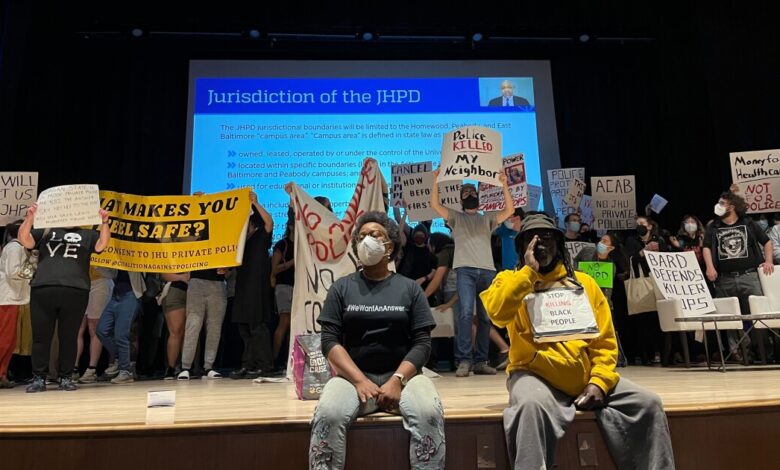

Instead, protesters overtook the stage, chanting “no justice, no peace, no Hopkins police” and carrying signs with the names of people who had been killed by police at other colleges: Scout Schultz at the Georgia Institute of Technology, Tyrone West near Morgan State University. An audio recording of police sirens flooded the auditorium.

The interruption forced the town hall to go online, where officials from the university and the Baltimore Police Department presented the draft agreement and answered questions. Two more town halls are scheduled for this month.

“At Johns Hopkins, we strongly value free expression and fully support the right to protest,” Megan Christin, a university spokesperson, said in a statement to The Chronicle after the event. “We also believe we must be able to engage civilly across our differences and have difficult conversations about the challenging issues we face together as a community, such as public safety.”

Tensions over the police force have been simmering since it was announced four years ago. On Thursday, those tensions boiled over, revealing a university and a community deeply divided over the placement of police on campus.

Protesters put a stop to the town hall that had been scheduled to discuss Hopkins’ planned police force.

Johns Hopkins announced its intentions to create a police department in 2018. Baltimore has long struggled with crime, routinely ranking among the U.S. cities with the highest homicide rates per capita.

In a 2018 email to the community, Johns Hopkins’ president, Ronald J. Daniels, and Paul Rothman, chief executive of Johns Hopkins Medicine, cited “the challenges of urban crime here in Baltimore and the threat of active shooters in educational and health-care settings” as reasons for creating the department.

“Johns Hopkins’ current security program is unusual among its peers,” the leaders wrote. “Almost every other urban research university, across the country and in Baltimore, has a university police department as part of its security operation.”

The proposal was met with pushback. In 2019, students staged a monthlong sit-in to protest the force and the university’s relationship with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Several were arrested.

After the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing racial-justice protests in 2020, Hopkins put its plans on pause. Students and staff called on Hopkins to scrap its plans altogether, but the university marched on.

Last month, the institution’s vice president for public safety, Branville Bard Jr., announced plans to roll out a “progressive” police department by the fall of 2023. The plans were again met with swift opposition.

By choosing to push forward with a police department, Hopkins confronts some of the trickiest ethical questions facing colleges today: To what extent should student and staff opinions inform university policy? How much power can accountability boards really leverage? And how can colleges balance conflicting definitions of safety?

How it answers these questions could inform how other colleges handle policing and public safety in a fraught environment.

A Plan for Policing

Hopkins currently employs over 1,200 unarmed public-safety personnel across its three Baltimore campuses. When police officers are needed, the university relies on the Baltimore Police Department and off-duty officers on campus to respond.

The new department, Bard wrote in his August 23 email to the Hopkins community, would employ up to 100 personnel, including patrol officers, supervisors, command staff, detectives, and community-relations officers, and allow Hopkins to become less dependent on off-duty Baltimore cops.

The university’s private police force would also face “multiple layers” of community oversight. In 2019 when the state legislature approved Hopkins’ request to assemble a police department, it tacked on a series of accountability requirements — including a complaint process, an accountability board, body-camera requirements, and compliance with Maryland’s public-records law.

Last week, ahead of the town halls, Hopkins released a draft of its memorandum of understanding with Baltimore police, outlining the new police department’s area of jurisdiction and responsibilities. The agreement will be finalized after a comment period ends in November.

According to the memorandum, the Johns Hopkins Police Department will have jurisdiction over its three campuses and the public sidewalks and streets adjacent to them. Baltimore police will have primary responsibility for investigations and arrests in more serious cases, including murder and rape.

Hopkins will be able to hire a maximum of five Baltimore Police Department officers each year and will not be allowed to “directly solicit” Baltimore police officers for employment, a measure designed to prevent worsening the staffing challenges for the city’s police department.

Bard said he expects the draft memorandum to change in response to community feedback, but that community members should temper their expectations as to how much the memorandum will change. The document is supposed to be narrow in scope, Bard said, and some suggestions may be more appropriate as policy. The agreement will be in effect for seven years.

At this point, how much the department will cost Hopkins is unclear, Bard told The Chronicle. Typically, a force of 100 police officers will cost $7.5 million to $8.5 million a year, he said.

“Whatever that number is,” Bard said, “the public will be made aware of it.”

‘A Slap in the Face’

The push to remove police officers from campuses gained momentum during the nationwide racial-justice protests of 2020, when activists put a spotlight on injustices committed by campus police officers and called on their institutions to cut ties with local police departments.

Following the killing of George Floyd in May of 2020, students pressured the University of Minnesota to dissolve its relationship with the Minneapolis Police Department. The university eliminated some contracts with the department, but not all.

Killings by local police officers spurred students at Ohio State University and the University of Louisville to demand that their institutions sever ties with their local police departments. The institutions never did.

And last fall, Portland State University announced its campus police force would patrol unarmed, but to some activists’ disappointment, it allowed the campus-safety office to remain armed.

Having a private police force on campus “is like a slap in the face after everything that police have been doing to African Americans … in this country for hundreds of years.”

Baltimore became a national focal point of police violence against Black people in 2015, when 25-year-old Freddie Gray died in police custody. Following his funeral, tensions between residents and police escalated into rioting. None of the six police officers involved in Gray’s death were found guilty of any crimes.

The 2020 protests put Hopkins, which had announced its vision for a police force two years prior, in the hot seat. Thousands signed a petition calling on Hopkins to drop its plans. In mid-June of 2020, university leaders announced they would suspend the rollout for at least two years.

The pause, officials wrote, “will give us the opportunity to focus on the opening that we have now in the debate on public safety and to invest our energies in that endeavor.”

“It gave the university time to see what reforms were coming down from the state level,” Bard said. “It also gave us time to look around the country and see what new and best practices were being developed nationally.”

For example, Bard said, the university’s new behavioral-health crisis-support team and community-safety innovation fund were inspired by national practices.

The behavioral-health crisis-support team, which was created last year, pairs licensed mental-health clinicians with campus-safety officers to respond to behavioral-health crises on and near campus. The community-safety innovation fund supports community programs working to stop violence in Baltimore. In 2021, the university announced nine grantees for the $6 million project.

Bard also said that the pause allowed him to hear from the surrounding community when he arrived in Baltimore last year after serving as the police commissioner of Cambridge, Mass.

“So many positive things came out of this,” Bard said. “It gave me an opportunity to engage with many stakeholders — staff, students, neighborhood associations — and learn from the community what the community expected of public safety and of the impending police department.”

But some activists see the decision to proceed with a police department as ignorant of what they have been demanding for several years. Instead of withdrawing from policing, Hopkins is embracing it.

Tyshera Mintz, a sophomore at Hopkins and the events chair of the Black Student Union, said the decision makes her feel like the university doesn’t care about Black students.

“We came here for a better education. We came here to do something with ourselves,” she said. “But then to hear something about a private police force coming onto the same campus where we reside is like a slap in the face after everything that police have been doing to African Americans, Black people in this country for hundreds of years.”

Gnagna Sy, a sophomore at Hopkins and the outreach chair of the Black Student Union, said that the possibility of running into a police officer “adds a burden that you shouldn’t have when you’re walking around campus.” This burden will disproportionately affect students of color, she said.

“I already feel safe going to all of my classes, day or night,” Sy said. “I will walk through this campus freely at 3 a.m.”

Several community members said this is just the latest transgression by a university that has extracted land and resources from Black Baltimoreans for years. More than 60 percent of Baltimore residents are Black.

Rachel Viqueira, a Hopkins alum, Baltimore resident, and epidemiologist, referenced how the East Baltimore Development Inc., a $1.8 billion project affiliated with the university, displaced about 800 families in Baltimore’s Middle East neighborhood to create a bio-tech park.

“I firmly believe that implementing this police force would be one way to make that unused real estate more appealing to investors and other people to build housing or medical facilities on top of it and build a sense of control,” Viqueira said.

Viqueira said she does not believe the new department will reduce crime, because it doesn’t address root causes, such as poverty and displacement.

“It’s just going to continue to push out residents who don’t fit the image that Hopkins wants,” she said. “It’s a very real threat to their lives.”

Donald Gresham, a Baltimore resident and president of the Baltimore Redevelopment Action Coalition for Empowerment, said he and other residents are concerned about armed officers lacking familiarity with the community and its members. For example, he said, an officer might think that a resident is having a medical emergency and acting irrationally, but the resident’s neighbors know that he is homeless and this is normal behavior.

“I’m concerned that many people of color are going to end up dead,” Gresham said.

‘The Horse Has Already Left the Barn’

Bard, Hopkins’ vice president for public safety, said he shares community members’ concerns about racial disparities in policing. He said that’s why he is committed to the Racially Just Policing Model Policy created by the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts and Bridgewater State University.

“If you worry about pollution, the answer can’t be ‘don’t breathe the air,’” Bard said. “The answer is to clean that much-needed resource. That same logic applies to policing.”

Bard envisions creating a model of progressive and community-oriented campus policing. At the Cambridge Police Department, Bard created a public database tracking police interactions among different racial groups. He plans to create a similar dashboard at Hopkins.

“People want, and know that they need, good policing,” he told The Chronicle. “They just don’t want the negative aspects of policing. I’ve had a lot of support for a small, publicly accountable, university police department.”

People want, and know that they need, good policing. They just don’t want the negative aspects of policing.

Compared to other top-ranked institutions, Hopkins is fairly late to the game in assembling a police force. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard and Yale universities, and the universities of Chicago and Pennsylvania all have police departments, and Princeton and Stanford universities employ sworn officers in their public-safety departments. Efforts to remove police from campus have been active at many of these institutions.

Kristen Roman, chief of police at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, said that for colleges, one of the advantages of having a police department is that officers are more familiar with the institution’s particulars.

“As a community member, I myself would rather have somebody in a police role who is invested and understands some of the unique challenges of my community,” said Roman, who serves as director-at-large of the International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators’ Board of Directors.

Steven J. Healy, a co-founder and chief executive of the campus-safety consulting firm Margolis Healy, said he can’t think of any other institutions that have assembled their own police forces in recent years.

“The horse has already left the barn on that one,” Healy said. “Hopkins is probably one of the last institutions that is in an urban center that has been significantly impacted by crime in recent years that is making that decision.”

Still, Healy said, other institutions can take away some best practices from Hopkins’ rollout.

Healy applauded Hopkins’ transparency about its process, especially in light of Baltimore Police Department’s well-documented issues with corruption and racial injustice. He said he was also impressed by the university’s investments in efforts to address the root causes of crime.

“The biggest takeaway is how thoughtful the university has been in terms of listening to the diverse voices … and being very candid around what it intends to do to make its model of policing different than what folks may have, in this context, in Baltimore, experienced,” Healy, a native Baltimorean, said.

But of course, Healy said, it would be impossible to get everyone on board with campus police.

“Ultimately, the institution has to make the right decision,” he said. “It has to make a decision that it believes will advance campus safety for all members of the campus community, and in Hopkins’ case, in the local community.”

[ad_2]

Source link