She Was Denied Tenure at Harvard. But She’s Not Done Fighting for Change in Academe.

[ad_1]

Two and a half years ago, many professors wondered just how broken the tenure system must be if Lorgia García Peña wasn’t considered worthy.

García Peña, who came to the United States from the Dominican Republic as a child, was the only Black Latina scholar on the tenure track in Harvard University’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. In 2019 her department committee unanimously recommended her for tenure, and the college-level appointments and promotions committee endorsed that decision. But once her case reached the administration, she was denied.

That move sparked outrage, with thousands of students and faculty members across the country signing letters to Harvard’s president, Lawrence S. Bacow. On campus, Harvard students held rallies to support her.

According to an article published last year in The New Yorker, some Harvard professors saw García Peña’s work as activism and not scholarship — a common challenge, according to ethnic-studies scholars. At one point, her assigned mentor suggested she withdraw an already-submitted manuscript and change the direction of her research, The New Yorker reported. But most of the tenure process went smoothly, and many students sung her praises.

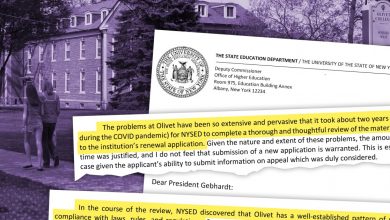

After García Peña’s tenure denial, she filed a grievance. A panel of professors alleged that she’d faced discrimination and recommended that Harvard’s administration review the decision, according to The New Yorker, but that didn’t happen. A spokesperson for Harvard told The Chronicle this week that the university doesn’t comment on tenure cases. The dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences did agree to a review of the tenure process, and changes to increase transparency and reduce bias are being made now.

In a new book, Community as Rebellion: A Syllabus for Surviving Academia as a Woman of Color (Haymarket Publishing), García Peña writes about how her experiences at Harvard and elsewhere in higher ed have shaped her, as a professor from a marginalized background, how she finds hope in times of struggle, and how scholars of color can act to dismantle inequitable academic structures.

García Peña arrived at Harvard in 2013, leaving a tenure-track post at the University of Georgia. While in Athens, Ga., she co-founded “Freedom University,” a project that seeks to teach and uplift undocumented students. The program began after such students were barred from attending some of Georgia’s public colleges in 2010. García Peña is now an associate professor of race, colonialism, and diaspora studies, with tenure, at Tufts University.

García Peña’s spoke recently with The Chronicle in her first interview with a journalist since her tenure denial. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You actually didn’t start writing this book after your tenure denial at Harvard. It was after an academic conference where you said that you and other scholars felt silenced. What happened?

At the end of 2018, I had gone to a Dominican-studies conference. And this is just an example, because I’ve seen these dynamics in other conferences, but there was a lot of resistance to change. For those of us who are interdisciplinary scholars, being in institutional spaces — be it a conference or department — there’s always a push and pull, because there is this traditional way of understanding knowledge and knowledge-making, and then there is this other way. I tend to answer questions rather than follow a discipline.

At this conference, one group of us — all women — were trying to push for a different structure that would allow for newer voices, younger people, and more inclusive leadership. It was very clear that we were not heard. So we decided to put together our own conference — a symposium that was, in many ways, the antithesis of what we had just been through.

After the symposium, I began to write what I thought was going to be a long letter to my graduate students. I wanted to share a little bit of what my path was and what working together with these two other women had done for me, in terms of thinking about the academy and the work we do as hopeful — as a site of hope rather than only as a site of struggle. I’ve had so many conversations with students over the years: How do we do this? How do we survive this? That was the impulse originally. Then the whole thing with my tenure happened. I just kept writing.

You wrote about how, when you were at Harvard, you realized that the university thought of you as “the one” scholar in Latinx studies. You noticed that some of your colleagues in the field perceived that your success was limiting theirs. What consequences does that have?

There isn’t a critical mass of scholars in any of these institutions doing this work. Most of these institutions have one or two people, and it never moves beyond that. The ripple effect of that is, you have people competing for the same jobs. But there is only one job, right? An English department will hire one scholar of ethnic literature.

The institution is making us see each other as competition — “if this person gets that, then I won’t get it” — because there’s only going to be one of us. This varies from institution to institution. I think it’s particularly pronounced in places, like Harvard or Yale, that already operate under this logic of “We are special, and we are unique, and therefore if you are the chosen one, you are even more unique.”

You said you weren’t prepared for the silence of your colleagues after your tenure denial. What do you think was driving that?

Complicity. They didn’t feel responsible, if they weren’t the ones denying me tenure. But in structures of exclusion, people who are benefiting from the systems have to think about their role in it. How is it that you are able to obtain tenure and I’m not?

You never questioned the inequalities. You never questioned the fact that someone else is doing stuff that you don’t have to do. I was an affiliated faculty to five different units at Harvard, and I was in two departments, and I had 24 graduate students. The amount of labor that I was doing was much more than the average faculty member.

When you are someone who is benefiting from my labor directly, and you’re not questioning what your role is in that, and you’re silent after an injustice, you’re part of the problem. That’s always heartbreaking for me, because the only way that we can have actual change is if everyone recognizes their role, as small as it can be, in creating the problem, or at least in sustaining it.

You wrote that scholars of color sometimes need to withhold their labor. How do you go about making the decision of “Do I do this or do I not?”

Ethnic studies is coming to save academia, if universities allow it.

I’m still learning to say no. That’s a lesson that a lot of us are still learning, especially women. I think a lot about what the impact of what I’m being asked to do would have on the students. Is this something that would, in some way, make the project that I’m invested in better? Or is it just labor that is meant to make me some sort of poster child for the university? And it isn’t always clear. For me, it’s really about creating spaces for students, especially first-generation students of color.

You want to create those spaces for students, but it also takes a lot of work, and you’re not necessarily rewarded for that. It seems as if you’re torn.

Every day. And it’s not just students; it’s also your field. You have people writing in from universities asking you to evaluate tenure cases. I get, on a weekly basis, at least five requests to evaluate books or articles. There are all of these things you don’t get paid for. But you do it, because I worry that if I don’t evaluate this manuscript on Black Latinidad, they will send it to somebody who’s unequipped to do it. When you’re in a small field like I am, you start to think about the impact that your saying no to this tenure case will have on the person who’s being evaluated.

Why do so many institutions, as you see it, not commit to ethnic studies?

Oh, that’s a very easy answer. The goal of ethnic studies is basically to dismantle and abolish the university as it is. We have all of these conversations about curriculum and hiring and retention and diversifying the faculty. But people still want to do things the way that they’re used to doing. And the way that we’re used to doing academia is Eurocentric, it’s anti-Black, it’s colonial, it’s misogynist, and it’s elitist, and it needs to change. Otherwise, we’re doomed. Ethnic studies is coming to save academia, if universities allow it.

People in higher ed talk about how “we are committed to becoming an antiracist institution.” What you’re saying is, They say that, and then …

It’s lip service. I call bullshit. So we have the murder of George Floyd. We have, the next day, all of these universities issuing statements about their support for Black faculty, including Harvard, at the same time that they’re firing me — the only Black Latina on the faculty. Their commitment to race and equity does not go beyond writing documents that nobody reads.

There are efforts in higher ed to try to diversify the scholarly pipeline: postdoc programs, fellowships, cluster hires. Do you think those efforts will work?

They can have a positive impact. A lot of universities are quite good at the cluster hire. But then they make no efforts once the people are there to support them, to retain them, to tenure them, to promote them. We have to understand that not everyone arrives at the university — faculty and students — the same way. Some people get to academia, and they’re the fourth-generation professor in their family. Others are learning on the go.

We continue to talk about race, but we don’t talk about class, when it comes to faculty in particular. I had a very challenging time when I started as a professor at the University of Georgia because I was in so much debt. I was coming from many, many years of making under the poverty line, and I had a newborn baby. All of a sudden, everything is based on reimbursement, and you’re supposed to max out your credit cards. If you’re 30 years old and a new professor, you don’t know how to talk about those things.

To go back to what happened at Harvard — now that some time has passed, has your perspective on that experience changed at all?

Not really. If anything, distance just makes it more and more clear that what I went through was terrible. And I don’t mean just the tenure denial. Tenure denial was the climax of what I would define as an eight-year abusive relationship.

It’s still hard for me to even drive by Harvard Square. I live in Boston, so that’s not easy to avoid. It’s still heartbreaking when I walk into one of my former colleagues at Whole Foods, and they look the other way because they are ashamed, or because they don’t want to be associated with me. I have graduate students who are finishing their Ph.D.s, and I was the one who mentored them and got them to that finish line. But I can’t go to their graduation because I can’t be in that space. That’s hard.

You can’t just forget it.

I still have students for whom I am the main adviser, who are writing dissertations with me. They’re Harvard students. It’s a really fucked-up position to be in, because my choices are: I abandon students that I have been working with for five, six, sometimes seven years, or I do this free labor for Harvard. I have to sit in rooms with colleagues, rooms at Harvard in which I am in a dissertation defense or in a Ph.D. exam. It’s triggering.

[ad_2]

Source link