The High Court’s Ruling on Admissions Exempts Military Academies. What’s Up With That?

[ad_1]

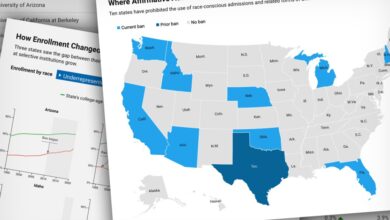

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on Thursday delivered a tremendous blow to race-conscious admissions policies — policies that selective colleges say have been a cornerstone of their efforts to bring racial diversity to their student bodies. But the court made an exception for one type of institution: military academies.

The carveout was written in small print as a footnote at the bottom of the 30th page of Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.’s 40-page opinion.

The United States government, he wrote, “contends that race-based admissions programs further compelling interests at our nation’s military academies. No military academy is a party to these cases, however, and none of the courts below addressed the propriety of race-based admissions systems in that context. This opinion also does not address the issue, in light of the potentially distinct interests that military academies may present.”

Potentially distinct interests. Roberts did not spell those out, adding a layer of complexity to the ruling that colleges across the country are now trying to parse and interpret.

To the dissenting justices, the footnote was another weakness in the majority’s argument that race-conscious admissions policies violate the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

“The court has come to rest on the bottom-line conclusion,” wrote Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson in one of two dissenting opinions, “that racial diversity in higher education is only worth potentially preserving insofar as it might be needed to prepare Black Americans and other underrepresented minorities for success in the bunker, not the boardroom.”

“To the extent the court suggests national security interests are ‘distinct,’” Justice Sonia M. Sotomayor wrote in the other dissent, “those interests cannot explain the court’s narrow exemption, as national security interests are also implicated at civilian universities.”

She noted that Roberts justified this carveout in part by saying that military academies were not parties in these cases. But neither, Sotomayor pointed out, were many other kinds of institutions, including religious ones, that did not receive similar exemptions.

Puzzlement — and a Sliver of Hope

Some higher-education scholars were left scratching their heads about how to interpret the footnote.

“It is not obvious to me why these institutions are treated differently,” Dominique J. Baker, an associate professor of education policy at Southern Methodist University, wrote in an email. “What are their interests that may be different than any other occupation in the United States that allows for them to need race-conscious admissions?”

Liliana Garces, a legal scholar and professor of higher education at the University of Texas at Austin, said she also struggled to make sense of it. She echoed the dissenting justices’ argument that if the military is able to use this practice, why not institutions that prepare students for professions in health care or business?

“It really shows the mental gymnastics needed for the court to overrule 45 years of precedent,” Garces said.

Kimberly West-Faulcon, a law professor at Loyola Marymount University, saw the carveout as a potential opening for colleges. The majority may have ruled against colleges’ diversity-based argument for race-conscious admissions — that a racially diverse class is necessary for colleges to achieve their education goals — but national security interests for race-conscious admission might still stand.

It really shows the mental gymnastics needed for the court to overrule 45 years of precedent.

“I read this case as cause for universities to review their admissions policies, conduct disparity studies, and be prepared to legally defend race affirmative action as justified by an assortment of compelling purposes,” she said in an email. National security may be one of those purposes.

In a friend-of-the-court brief filed in this case, 35 former military leaders argued that race-conscious admissions are crucial to their institutions’ decadeslong effort to diversify their officer class.

Federal courts have long deferred to the professional judgment of the military, said Ty Seidule, a visiting professor of history at Hamilton College, in New York. Roberts’s carveout may be a continuation of that practice.

In their brief, the former military leaders wrote that the importance of maintaining a diverse officer corps has been settled for decades.

“History has shown that placing a diverse armed forces under the command of homogenous leadership is a recipe for internal resentment, discord, and violence,” they wrote. “By contrast, units that are diverse across all levels are more cohesive, collaborative, and effective.”

Even after the military was desegregated in 1954, the officer corps remained almost entirely white. During the Vietnam War, the brief said, there were “widespread instances of racial tensions, disruptions, and violence.” After the war, the military embarked on an effort to change the demographics of its leadership, using “race-conscious affirmative action.”

The effort is ongoing, but according to the brief, the military has made progress since the Vietnam War. In 2020, it said, roughly nine percent of the officer corps was African American. The portion of Black officers in the Marines and Air Force was smaller: 5.7 percent and 6.3 percent, respectively. At that time, there were 1.3 million active-duty soldiers, of which roughly 17.2 percent identified as African American.

The former military leaders said there is still work to be done. For one of the brief’s signatories, Gen. Thomas P. Bostick, that was clear when he returned to the United States Military Academy at West Point, his alma mater, in 2013 after he had become commanding general of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

When he graduated in 1978, Bostick was the only Black cadet to go into the Army Corps of Engineers, he said. Now, looking at the group of more than 100 cadets who chose the same path, he saw only two Black cadets.

“We grow leaders,” Bostick said of the army. Referring to the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, or ROTC, he added: “You start with what you get out of ROTC and West Point. If your start lacks diversity, then you’ve got a long road.”

Bostick noted that even more officers come from ROTC programs than they do from military academies. While he was glad the ruling created a carveout for military academies, he worried about the ruling’s effect on that program.

[ad_2]

Source link