These Are the Books That Colleges Think Every Freshman Should Read

[ad_1]

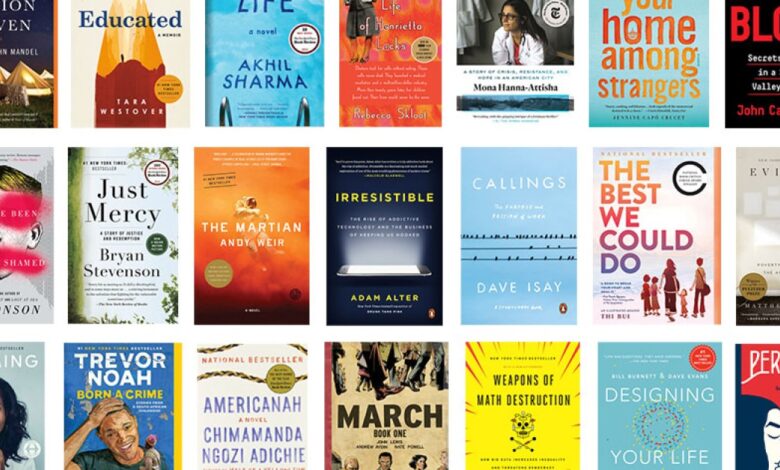

But those students won’t be reading just any book. It will be a “common reading,” a book selected by their institution to create a shared experience and be the subject of group discussions among freshmen. Some of the books are intended to help raise awareness of social issues, and are the subject of lectures, performances, or author visits.

The tradition goes by many names. It’s “One Book, One Campus” at East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania and Pierce College. It’s called “The Big Read” at Purdue University and at the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith. At Sussex County Community College, it’s called “Campus Novel.” And Washburn University’s common-reading program is dubbed “iRead.”

As varied as the names of the programs is what students read. The Chronicle analyzed four academic years’ worth of common reads — more than 1,064 titles at more than 700 institutions — to learn more about the books students are asked to read and the topics explored.

Among the findings: Students don’t always read books. Individual essays, poems, short stories, a podcast, TedTalks, films, and even a Netflix series (BoJack Horseman, if you’re wondering) all made an appearance.

Personal narratives were especially popular: One out of five assignments were biographies or memoirs. The topics of the common readings included immigration, education, technology, politics, history, and psychology, among others (see the Methodology section below for more information about how we categorized the main themes).

Check out more trends, and explore the data set, below.

Explore the full data set below.

SOURCE: Penguin Random House Common Reads

Methodology

The Chronicle’s analysis is based on the common first-year reading lists compiled by the publisher Penguin Random House for four academic years: 2017-18, 2018-19, 2019-20, and 2020-21. The lists are not comprehensive, meaning that some colleges’ common-reading programs are not included or are not included in every year. The lists may have been updated by Penguin Random House since mid-May, when The Chronicle downloaded the titles to analyze them.

Forty-three institutions were excluded from the data set because their common-reading programs were suspended due to the pandemic or they did not list individual titles.

The dates of publication are grouped by decade for ease of sorting and presentation. For books, the date is based on the year the work was published, according to the Library of Congress or Goodreads. For films, podcasts, videos, and TV shows or series, the publication date is when they were first aired. For speeches and lectures the publication date is when they were first delivered, except for those labeled in the lists as part of a book that was published later. The publication date for plays is when they were first published.

In general, we used the Library of Congress or Goodreads to determine what topics to assign to each work. In some cases, we also used a combination of book summaries, book and video excerpts, and our best guesses.

Although some works spanned multiple topics, we limited the number to three for each title and chose the ones that seemed to best fit it. The number of topics in the entire data set was limited to 53; some of them are meant to encompass more-specific subject areas. For instance, “Health” covers books about physical and mental health, and “Crime/Criminal Justice” refers to true-crime stories, accounts of gun violence, and books about the criminal-justice system. “African American,” “Native American,” “Latino/a,” “Asian American,” and the like cover works whose subject matter centers on those racial or ethnic groups.

Genres represent subcategories within the various formats of the works. For example, fiction, nonfiction, and biography/memoir are genres within the book format. Films, TV shows, videos, and paintings are genres of the visual-arts format.

[ad_2]

Source link