These Colleges Cut Back During the Pandemic. Except When It Came to Their Presidents’ Pay Packages.

[ad_1]

As he concluded his message, Cesareo sought to reassure employees that the suspension of their retirement benefits would help Assumption emerge from the crisis in a stronger position. Though spending cuts were needed, the university’s balance sheet and long-term financial outlook were stable, he said. And faculty and staff members could trust him to be open and honest as the university navigated the pandemic’s fallout.

“What I can promise is that I will continue to be direct and forthright with you as we address these challenges,” Cesareo wrote, according to an email obtained and authenticated by The Chronicle.

What the recipients of Cesareo’s email could not know was that just 16 days prior, Assumption had adopted a deferred-compensation plan for the man himself. Such deals are common tools used by colleges and universities to pay their chief executives and other top employees. Institutions and their trustees often describe such arrangements as necessary components of many executive contracts, because they help attract and retain highly valued employees who do difficult jobs in an increasingly competitive labor market. But such agreements, especially those that were established amid some of the worst months of the pandemic, also raise larger questions about institutional priorities — and about whose contracts can be reneged on, and whose are inviolable.

Here’s how such plans work: Generally, an institution commits to set aside or credit money each year into a prescribed plan established for a certain employee, and that employee can’t withdraw any money from the plan until an agreed-upon vesting date. Should the employee leave or be fired before the terms of the contract are satisfied, they forfeit a claim to the compensation accumulated in the plan, said George Birnbaum, a lawyer who represents and advises college executives and managers in contract negotiations. As a result, presidents generally stay at institutions longer than they might otherwise, which provides colleges with stable, long-term leadership, he said.

Because of the nature and timing of financial-reporting disclosures, these agreements and the scale of their payouts often don’t become public until long after they’ve vested. But private companies are legally required to certify “top hat” compensation agreements with the U.S. Department of Labor no more than 120 days after they are established exclusively for one or more employees who qualify as management or as “highly compensated” — though institutions do not have to specify the recipient or the amount of money committed under the plan. The Chronicle’s reporting found Assumption was one of several private colleges and universities to establish such plans with select employees during 2020, a year that saw athletic and academic programs eliminated, paychecks and benefits slashed, and higher ed’s work force decimated. At least two other institutions established top-hat plans for their presidents last year. Another 14 colleges entered into such plans with more than 100 nonpresidential employees. Fewer institutions of higher education registered top-hat plans with the Department of Labor between March and December 2020 relative to the same nine-month span in previous years. A total of 17 private institutions disclosed top-hat plan information during this period of 2020, compared to an average of 24 institutional notifications filed in the three years preceding the pandemic.

For this report, The Chronicle spoke with more than a dozen current campus officials and employees, many of whom were reluctant to criticize their institutions’ board or leadership on the record, fearing future retaliation.

Adrianna Kezar, director of the Pullias Center for Higher Education at the University of Southern California, said that cost-cutting actions like the ones taken by Assumption reflected a broader trend across higher education in 2020. Despite the expectations of yearslong employment that a president’s deferred-compensation plan, and, say, a tenure-track faculty contract both imply, administrators and governing boards seemed to view the former as an investment in a college’s survival and viability, and the latter as a drain on resources or even an existential threat. Such a premise could conceivably make it easier to rationalize cuts to operations and work forces, Kezar said, instead of considering alternative strategies.

“Of course, the role of the president isn’t interchangeable with that of an individual faculty or staff member,” Kezar said. “But they do make large decisions for whole groups of people who contribute very significantly to a university’s mission. And collectively, the faculty and staff matter as much as the president.”

Mark Harris for The Chronicle

Moreover, as Assumption came to better understand the ramifications of the pandemic last year, its president elected to take a 10-percent pay cut, Guilfoyle said. Assumption paid Cesareo just over $378,000 in base and other taxable compensation in 2019, as well as $59,000 in nontaxable benefits, according to the most recent available filing from the Internal Revenue Service. Assumption and Cesareo also announced a five-year contract extension for the president in May 2020.

Regardless of the optics surrounding Cesareo’s 2020 deferred-compensation deal, the president’s leadership during the pandemic validated the institution’s investment, said Cary LeBlanc, campus program director of Assumption’s Rome outpost, during an interview over Zoom arranged and attended by Guilfoyle. LeBlanc also lauded Cesareo’s fund-raising skills, which have helped Assumption establish new schools and erect buildings in recent years.

“He has steadily progressed in making sure that the university is realigning itself with what is important,” LeBlanc said.

Assumption’s president and faculty began clashing almost immediately after Cesareo became president in mid-2007, recalled LeBlanc. In December of that year, the faculty accused Cesareo and his administration of violating institutional policy when the college refused to host a gay activist veteran as a Veterans Day speaker.

In 2014, Assumption laid off 15 members of its faculty and staff. The following year, Cesareo’s base pay increased by nearly $56,000, and the college established a five-year deferred-compensation plan with a vesting date on June 30, 2020. Between 2015 and 2020, the college credited at least $138,000 into this plan.

Tensions boiled over in 2017, when faculty voted no confidence in Cesareo’s leadership after repeated rounds of layoffs and enrollment declines under the president’s tenure. Unmoved, the board reaffirmed “absolute confidence that the college is moving in the right direction under President Cesareo’s leadership,” the trustees said in a statement. “We express our gratitude to him for carrying out the board’s priorities to build upon Assumption’s exemplary academic reputation.”

Since then, relations between the faculty and the president have improved, said LeBlanc, matching a sentiment expressed by Assumption’s faculty senate leadership last year. This peace might not last, though. Late this September in another letter to Assumption’s faculty obtained and authenticated by The Chronicle, Greg Weiner, the provost, proposed the elimination of various academic programs that would result in job losses for three tenure-track or tenured faculty and cutbacks in spending and other labor.

Echoing the words Cesareo had sent out the year before, Weiner emphasized the strength of Assumption’s financial position. And he cast his proposal as a proactive countermeasure against future declining enrollments — the demographic cliff forecasted to slam private universities and colleges in the Northeast especially hard. The moment necessitated immediate action, Weiner argued, “precisely because a crisis is not yet here and we still have time to reposition ourselves to emerge stronger from it.” Still, the provost acknowledged how his proposal would read to a weary faculty.

“I cannot, and do not, ask for the faculty’s enthusiasm for the Plan,” Weiner wrote. “No one is, or should be, enthused about any reductions that affect the livelihoods of our colleagues.”

Twelve days later, Rollins announced it would transition to mandatory online learning for the remainder of the semester. After scrambling for more than two months to educate its students under unforeseen and extraordinary circumstances, in May Cornwell relayed to his campus that Rollins would cut its budget for the upcoming 2020-21 academic year by more than 10 percent — a $16-million reduction — to counteract anticipated enrollment losses.

The pain, Cornwell wrote, “will be shared and felt throughout every corner of this community we cherish.” Very few, if any, departments in the Florida institution for 2,500 undergraduates would avoid being downsized. The college would temporarily suspend matching employee retirement contributions until 2021 (though the college’s 7-percent contribution would carry on). Fifteen percent of all positions were to be eliminated, and certain services outsourced. Some employees would be laid off.

“The only prudent course of action is to re-engineer Rollins to be smaller than we are now, not just next year, but for the foreseeable future,” Cornwell wrote in his mid-May 2020 message.

Despite the reductions, the deferred-compensation deal struck between Rollins and Cornwell would survive, remains effective today, and is anticipated to vest in 2025.

Like their counterparts at Assumption, Rollins’s trustees first contemplated establishing a deferred-compensation arrangement for Cornwell prior to the pandemic, in mid-2019, said Matt Hawks, the college’s associate vice president for human resources and risk management. Citing employee-privacy policies, Hawks declined to disclose the college’s annual contribution rate to the plan.

Hawks said he was unaware if either the college’s board or Cornwell ever considered aborting the February 2020 deferred-compensation agreement. Even though the arrangement made Rollins responsible for contributions for at least five years, canceling the deal carried its own risks, he said.

“Why in the world would we do that — heading into a global pandemic — when we needed an effective leader, which we had in Grant?” asked Hawks.

Along with the pink slips and contribution-match suspensions, Rollins instituted progressive pay cuts for all employees earning more than $45,000 — cuts that also applied to Cornwell, Hawks said. In fact, Cornwell elected not to take any salary during the fall 2020 semester.

Because it managed to avoid the most dire scenarios it had forecast, Hawks said, the college was ultimately able to restore its employees’ lost pay over the course of this past year, including Cornwell’s. In 2019, Cornwell earned $620,000 in base pay and received $88,000 in nontaxable benefits. But retirement benefits for faculty and staff members weren’t recovered.

Cornwell’s steady management during the pandemic also earned compliments from Jana Mathews, College of Liberal Arts faculty president at Rollins. Regardless of what compensation package had been negotiated prior to the pandemic, Mathews said, Cornwell had proved to be an effective leader for the college when it needed him most.

“While there is always room for improvement at any institution,” said Mathews, “I would argue that Rollins has navigated the Covid storm particularly well thanks to strong leadership.“

Around the time Northwood finalized these deferred-compensation deals, other facets of the university’s Covid-ravaged operation were coming into focus. Between November of 2019 and of 2020, Northwood reported the loss of almost a quarter of its work force (more than 150 employees), according to preliminary disclosures to the federal government. Part-time instructors lacking faculty status represented the largest share of these losses. Undergraduate enrollment also slumped by 14 percent between fall 2019 and fall 2020.

The university’s footprint also shrank since the pandemic’s start, with the closure of seven locations in Texas, Wisconsin, and Michigan, according to disclosures made to the U.S. Department of Education.

A representative for Northwood said the two plans were implemented in 2020 due to the terms of a March 2019 contract. Northwood declined further comment.

What’s important to remember about such plans in the first place, said George Birnbaum, the lawyer who advises colleges and executives, is that they’re necessary because the broad responsibilities and high expectations of the top job dictate that college presidents be compensated differently than other university employees. Proven leaders are in high demand during uncertain times, and if a university board isn’t willing to lock-in a well-liked incumbent president with a deferred-compensation deal, some other institution ultimately will, Birnbaum said.

“The people who are successful at this job — at pleasing a wide variety of constituents and tending to a university’s finances by securing donations — if you are successful at that, you’re going to get all sorts of calls from search firms,” said Birnbaum.

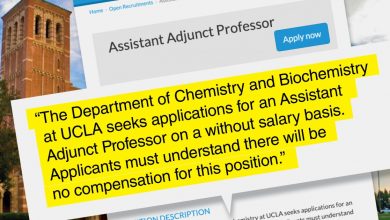

College presidents weren’t the only recipients of these plans during 2020.

At Davidson College in mid-September 2020, the institution entered into deferred-compensation plans with two employees: Christopher J. Gruber, vice president and dean of admission and financial aid; and Raymond A. Jacobson, chief investment officer. Neither employee responded to requests for comment. Requests for comment from Davidson’s media-relations office also went unanswered.

The Chronicle received a similar lack of response from the University of Pennsylvania. Jean-Marie Kneeley, formerly a vice dean for advancement who retired in September, could not be reached. Penn established a retention-bonus plan for Kneeley between June and October 2020, according to a disclosure to the Department of Labor.

Regardless of what form a top-hat plan might take, Adrianna Kezar, of Southern California, said such arrangements were symptomatic of higher ed’s penchant for duplicating practices from corporate America.

“It’s a problematic system that we’re replicating from the corporate sector, one which jeopardizes the integrity and the mission of organizations,” Kezar said. “There is no reason that executives in any sector should make so much more than the baseline employee.”

[ad_2]

Source link