When Dating Violence Is a Taboo Topic

In many ways, Dong’s death is sadly representative of other cases of dating violence: A partner with a volatile temper and a track record of abuse. A complicated reporting process where even seemingly clear-cut cases can fall through the cracks.

But Dong’s case is distinctive, too. The 19-year-old freshman was an international student from China.

The relatively limited research into international students and dating violence and campus sexual assault suggests that they are no more likely to be victims than their American classmates. In fact, in some ways they may be less at risk — for one, they tend to drink less than their peers, and alcohol consumption is often involved in cases of sexual assault.

Yet educators are beginning to understand ways in which international students may be particularly vulnerable. Dong’s roommate helped her report her boyfriend’s threats to authorities, who then failed to follow up appropriately. But international students’ unfamiliarity with American law may render the already confusing Title IX process especially opaque. Some victims may be hesitant to file a report for fear that rocking the boat in any way could jeopardize their student-visa status.

The challenges often run deeper than legal or procedural issues. Many international students come from countries where sex is not discussed openly, and education about sex and healthy relationships is nonexistent. “It’s like if you got to be 20 years old and you never learned your multiplication tables in math class,” said Kate Parnell, a sexual-health educator at Simon Fraser University, in British Columbia. “Now suddenly you have to do multiplication.” Other cultural norms, combined with language barriers, can further complicate international students’ understanding of sexual violence.

That can make it more difficult for them to obtain critical sources of support and assistance. That international students could be overlooked or ill-served even as they have become a more prominent presence on American campuses — before the pandemic, student-visa holders had grown to 5.5 percent of the overall college population — troubles educators. They say colleges need to develop more culturally sensitive approaches to sexual-assault education and to services that aid victims.

“We’re engaging with the whole college campus in the same way rather than taking a personalized approach,” said Veronica R. Barrios, an assistant professor of family science and social work at Miami University (Ohio) and co-author of a recent paper on international students and campus sexual assault. “How can we make sure that we are hearing these hidden voices?”

That’s not necessarily the case in the more culturally conservative countries that are home to many of the international students now in the United States. When Michael Blackman interviewed students from East Asian countries for his dissertation on international students and ideas about sexual violence, he found that they had had “no sex ed, to speak of.”

Adopting the Mandarin word for “consent” doesn’t necessarily make sense to Chinese students without additional context.

Assault-prevention trainers at American colleges “think they can just stand in a room and rattle off topics like consent and penetration,” said Blackman, who is now dean of students at the University of New Hampshire. But for international students, “these may not be concepts they have ever discussed.” Ideas that are assumed to be common knowledge among domestic students may need to be spelled out.

As a master’s degree student newly arrived from Taiwan, Yunling Chang found herself at sea when thrust into a Title IX session during graduate-student orientation. The high-level presentation assumed a familiarity with the topic that she just did not have, and as teaching assistants, she and her fellow grad students could be expected to be a resource for undergraduates in their classes.

“I don’t think I had a clear idea of what I was supposed to get out of the session,” said Chang, who is now a psychologist and a doctoral candidate at Texas A&M University at College Station.

But Chang, who has conducted research on Chinese students and their experiences of sexual harassment, said it’s not simply that students are unused to talking about such topics. In many countries, open discussions of sex — never mind of sexual harassment or assault — are considered inappropriate, even forbidden.

The shift to the American context, where such dialogue is not only accepted but expected in the college environment, can be jarring. For some students, it can also be intensely uncomfortable. “It can feel like such a taboo topic,” said Danielle Laban, dean of students and Title IX coordinator at National Louis University, in Chicago.

Sometimes that discomfort can cause students to shut down. Laban said an incident on her campus over the summer involved a sexually sensitive subject among a mixed group of students, and reticence among international students to discuss it had a chilling effect on the entire group.

At the same time, such sessions can be eye-opening for foreign students. A student from China, who asked not to be identified because of her concerns about speaking publicly, said she began to reassess the behavior of a former supervisor at her part-time job after she attended a sexual-health workshop with some friends at her large Midwestern university. The supervisor’s comments on her appearance, and his handsy behavior, had made her uncomfortable, but now she began to think, “Had I experienced sexual harassment, and I didn’t even know it?”

Not only their own cultural backgrounds but their perceptions of American culture, and its approach to sex, can affect how international students understand sexual assault.

Frequently, those perceptions are filtered through the prism of popular culture. Blackman said many of the students he spoke with for his dissertation had formed their ideas about American dating culture by watching the television show Friends, giving them the sense that Americans were more sexually open and had sex more freely and with more partners than was often actually the case.

Some international students may need to understand that although Americans may have more-liberal attitudes toward sex, permissiveness doesn’t equal permission, and their advances may be unwelcome or threatening. Studies of Chinese students, for instance, have found that they are more likely to identify overt actions, such as demanding sex in exchange for favors, as sexual harassment than to perceive covert ones, like pressuring someone to go on a date, as crossing a line.

Other international students may think that sexual assault is not an issue they need to pay attention to because they are not sexually active or don’t engage in activities they see as risky, such as attending fraternity parties. In a survey of Miami University students, international students were significantly less likely to believe they would be victims of campus sexual assault than were their domestic classmates.

That sense of invulnerability led some of the students in Blackman’s study to skip educational sessions on sexual assault or to pay only cursory attention. ‘They said, oh, it doesn’t apply to me,” he said.

For international students gleaning their information about sexual violence from movies and television, the threats are often portrayed as coming from strangers lurking in the shadows. At National Louis University, Laban said, sexual-assault-awareness educators have begun to emphasize relationship violence in their outreach to both international and domestic students.

“In English for academic purposes, we don’t usually talk about sexual assault or spermicide,” said Sharla Reid, director of Fraser International College, a program for incoming international students at Simon Fraser.

The terminology of sexual-assault awareness and reporting doesn’t always neatly translate, said Jill Dunlap, senior director of research, policy, and civic engagement at Naspa: Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education. For instance, Dunlap, who previously worked with campus sexual-violence survivors, said simply adopting the Mandarin word for “consent” doesn’t necessarily make sense to Chinese students without additional context. Instead, Dunlap found it was most helpful for students to provide concrete examples of situations in which consent is needed and of how to give it.

Students need to know this language, said Chang, the Texas A&M psychologist and researcher. “They need to know how to say ‘no.’”

Shannon Hutcheson, a doctoral candidate at McGill University, in Montreal, said that while it’s important for colleges and law enforcement to understand the impact of international students’ cultural and linguistic backgrounds, officials have to be careful about how those differences frame their own thinking. At times, such differences have been used to invalidate students’ experiences of sexual assault or even to discourage them from reporting, said Hutcheson, who has been studying court cases involving international students and sexual violence. “Authorities will question: ‘Are you sure you just didn’t have a cultural misunderstanding? Oh, I think you just don’t understand.’”

Navigating the reporting system for sexual assault and harassment can be daunting for anyone. Even American students often don’t understand which administrators have mandatory-reporting responsibilities, and whether by coming forward, students are initiating a formal complaint or merely confiding a trauma — all of which may keep them from seeking help.

International students may face additional barriers. Some come from countries with deep-seated distrust of law enforcement, so they may be reluctant to file a police report for a protective order. As student-visa holders, they may not think they have the same legal rights as students who are citizens. And wariness that any involvement with the legal system could jeopardize their visa status could prevent international students from coming forward, even when they are the victims.

“For me, the biggest barrier is the conditionality of international students’ status,” Hutcheson said.

Indeed, visa status can affect international students who have experienced sexual trauma. Student-visa rules require international students to be enrolled full time. While students can receive special exemptions to take a lighter course load, it’s not as straightforward for them as it would be for their American classmates to drop classes or to temporarily withdraw for a term as part of their recovery.

But the hurdles to pursuing legal remedies can also be cultural. In some East Asian societies, experiencing sexual harassment or assault is viewed as bringing shame to the victims’ families and damaging their reputation. Blackman, the New Hampshire dean, said some students hesitate to report sexual violence for fear of “starting an unstoppable chain of events.”

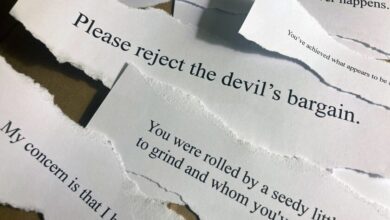

Had I experienced sexual harassment, and I didn’t even know it?

“They’re fearful that we will call their parents, that we will tell their teachers,” he said. “Sometimes you have to say explicitly, ‘No, I won’t call your parents.’”

Cultural factors can affect international students’ response to and recovery from sexual assault in other ways: In many cultures, mental-health challenges aren’t discussed, and therapy is stigmatized.

“So much of the burden is on international students to find information and to navigate the system,” she said.

One issue can be the silos that frequently exist within colleges. Responsibility for education and reporting rests with Title IX offices or those who focus on advocacy and prevention, while international-student-services offices are the home base for student-visa holders. The former may lack the cultural know-how to work with international students, and the latter may have an incomplete understanding of Title IX.

“If we’re not preparing to support these students in our professional development, then we might be missing something,” Laban said.

International students can fall through the cracks, said one college staff member who asked not to be identified because she wasn’t authorized to speak to the press. At her former institution, sexual health and assault prevention were part of her job duties in international programming, but at her current college, she was told to leave such work to other offices. As a result, there are no sessions specifically for international students, said the staff member. “It’s one of those ‘who’s on first?’ situations,” she said, “where no one takes responsibility.”

These situations can leave international students in an information vacuum: “Who are they seeking help from?” said Rose Marie Ward, vice provost of graduate education at the University of Cincinnati and an author, with Barrios and Kristen Budd, a sociologist at Miami, of a paper on international students and sexual assault.

One solution, Ward and others said, is to form more-intentional partnerships to reach international students. Offices of international-student services can be helpful in getting the word out about sexual-health and assault-prevention programming, because they have regular interactions with students because of visa and paperwork requirements. “We make sure they get an invitation to events from the people they trust the most,” said Laban, who also oversees the international office at National Louis University.

The international office can also help shape programming, advising in education and outreach efforts, as well as in counseling and support for victims. When Dunlap, of Naspa, was at the University of California at San Barbara, the international office was an “important feedback loop,” helping her understand the need to focus on the college’s large Chinese student population and to figure out what resonated.

International students themselves can also be an important resource. Mandarin-speaking graduate students helped Dunlap draft handouts and a presentation for Chinese students. At Simon Fraser, international students have volunteered as mentors for a sexual-health support group.

More colleges have begun to develop tailored, culturally responsive advocacy and sexual-assault education programming for international students. National Louis holds a session during international-student orientation. “We really wanted to get out in front of them early” to make sure they understand their rights and the reporting process, Laban said.

Other institutions have shied away from tackling such topics at orientation, when students may be jet lagged and overwhelmed by the transition to college and to a new country. At Fraser International College, where students take English and academic preparatory courses, a five-week module on sexual health and healthy relationships is incorporated into a mandatory semester-long course on making the transition to studying abroad. Yes, the college must spend money and staff time to do that, but Reid considers it “a pretty small investment in students’ experience.”

The course was inspired by Reid’s own experience studying in Japan, where she was sexually assaulted and struggled to seek help. It covers a lot of ground, including slang for talking about sex; basic sex ed, such as how to use a condom; and resources for dealing with sexual assault. In recent years, Parnell, the sexual-health educator, has tweaked the curriculum to include more discussion about gender identity and LGBTQ issues.

The course content is heavy on concrete examples, and students can pose questions anonymously. Parnell has enlisted popular instructors from other classes at the college to lead sections because students may feel more at ease around them.

It’s still awkward, Parnell said. “But I tell the students, if you talk about it, it makes it less awkward. And my hope is even if you’re just 10 percent less awkward, it will be the best thing for your own safety and the health of your relationships.”

Source link