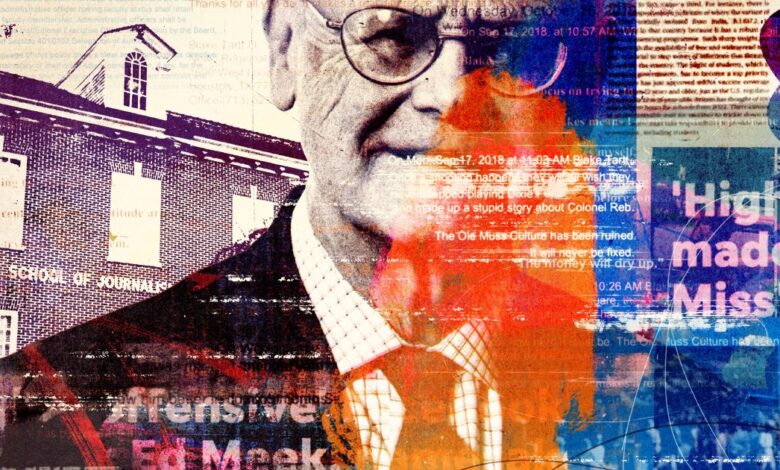

Downfall of a Dean

[ad_1]

As dean of the School of Journalism and New Media at the University of Mississippi, Norton dealt with them often. He attended football games and dinners. He thanked alumni for their sometimes-unsolicited input. He weathered bouts of public anger at the school, which was sometimes perceived, in the political ecosystem of Mississippi, as too liberal.

All of it he did well, it seemed, until an uglier side of being dean cascaded into view.

In March 2020, a mysterious group calling itself Ole Miss Information

acquired and started sharing emails between Norton and a real-estate investor whose support he seemed to have been courting. The investor had made racist comments to Norton. He’d referred to the tennis star Serena Williams with a gorilla emoji. He’d complained about “black hookers” and “gangbangers” and warned Norton about what happens when a town is overtaken by “the wrong elements.”

All this, and more, the dean did not protest. He either expressed vague agreement or ignored the businessman’s comments and moved the conversation along.

The public airing of those private exchanges was embarrassing and raised questions: When a potential donor or an influential alumnus expresses views that are antithetical to the stated values of a university, what should an administrator do? How much moral flexibility is required to raise money in higher ed? Where should the dean have drawn the line?

These questions feel especially urgent at the University of Mississippi, a place that has tried to extricate itself from Confederate symbols it once embraced, a place known more often by the plantation-era term “Ole Miss,” a place that many wealthy white donors wish would stay the same as it was when they were young.

The exposed emails might have started a productive, if difficult, debate among the journalism school’s faculty. Instead came recriminations, an erosion of collegiality, and charges of harassment.

After airing Norton’s exchanges, Ole Miss Information was not finished. It pressed the faculty to contend with Norton’s actions and to “free Ole Miss from its neoconfederate overlords,” writing in revolutionary prose about wanting a university that lived up to its ideals. It also sharply criticized the journalism school and pointed fingers at specific faculty members, saying that some were unqualified to hold their positions.

Where should a dean have drawn the line?

What began as “legitimate criticisms” had turned into “attacks,” tenured professors at the school wrote in a grievance letter. Black and international faculty members, in particular, felt targeted by the group. Seven people within the school filed a complaint alleging a hostile environment, and a university office began to investigate.

But the investigation brought only more drama. As part of the inquiry, the university ombuds fell under suspicion as somehow complicit in the work of the anonymous group. In turn, he sued the university, claiming in court documents that he was being retaliated against for doing his job. He has also denied being affiliated with the group.

It’s now been a year since Norton’s emails became public. The dean’s conduct created a mess. In an environment of suspicion, of anonymous emails and unclear motives, that mess became nearly impossible to clean up.

Immediately, he started hiring practitioners onto the faculty — people who had spent years in the field and did not have doctorates. He valued practical knowledge and teaching. He regularly told professors that few of their publications would outlive their students.

That hiring shift, in some cases, “rankled” tenured, research-based faculty members, according to the journalism school’s most recent accreditation site–team report, from 2016-17. It didn’t fit their vision for the school. At least a few thought that Norton wasn’t invested in supporting them. There emerged a sense among some of an “in group” that was called upon to make decisions and an “out group” that was ignored.

Meanwhile, the school’s enrollment grew explosively, mostly through the addition of an integrated marketing-communications program. To every prospective and admitted student, Norton would send a handwritten letter. He expanded the faculty, too, and focused on making racially diverse hires. To some instructors, he became an essential support.

In her five years at Mississippi, Mikki K. Harris, now a senior assistant professor of journalism and communication studies at Morehouse College, saw Norton’s office as a place of refuge. Once, Harris and a colleague, also a Black woman, were confronted by tailgaters at the Grove, where alumni and students party on game day. A man snapped Harris’s picture, told her she was “up to no good,” and got closer and closer. A woman said, “Go back to your country.” As they walked away, a student yelled the N-word.

“Our presence,” said Harris, “was threatening their party.”

Looking for guidance, Harris confided in Norton. He cried. Then he encouraged her to reach out to the chair of the school’s diversity committee and an associate dean, and said he would himself discuss the Grove incident with other administrators. “He’s compassionate. He cares,” Harris says.

Still, Norton, who is white, could make racially insensitive remarks. Jennifer Sadler, now an assistant professor of marketing at Columbia College Chicago, remembers an exchange during a graduation ceremony. Sadler, who is Black, asked Norton about his gold hood. The dean joked that it was his “Klan hood,” she says. Sadler felt incredibly uncomfortable.

By then, Sadler had decided to leave Mississippi. When she told Norton that she’d received another offer, he told her to take it, though he lamented that he couldn’t afford to lose a faculty member of color, according to Sadler. That, too, disappointed her, to be seen in that moment not as a whole professional.

Alex Williamson for The Chronicle

In general, Norton had a hands-off approach to the day-to-day management of the journalism school. Instead, he focused on drumming up funds and dealing with alumni.

One of the central relationships that Norton tended to — and one that would eventually implode — was with the school’s major benefactor, Ed Meek.

Meek had worked at the university for more than three decades, until 1999. He’d been the assistant vice chancellor for public relations and marketing, essentially in charge of the institution’s public image, and an associate professor of journalism. He and his wife, Becky, operated several businesses and had given the university $5.3 million to create an endowment to establish the journalism school, which bore their surname.

Meek recruited Norton, who was then dean at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, to run it. “Hand in hand,” they “tried to build a program. We shared a vision,” Meek told The Chronicle. When asked if he felt like he and Norton were on equal footing, Meek replied, “No, he’s the dean. … I’m there to help. Will called, and I responded. I didn’t tell Will what to do.”

Norton did not respond to interview requests from The Chronicle. But dozens of emails between the two men, obtained by The Chronicle through a public-records request, make clear that the dean felt, at times, beholden to the patron.

Meek was full of ideas — “He moves like his shoes are on fire,” a former professor who knew Meek as a student once observed — and he wasn’t shy about sending them to Norton. It was his idea that the journalism school include the marketing-communications program. Once he pitched to Norton a course or a seminar that would challenge students “to think of a world with none of the known current media” and to “search for their vision of what could or might be.” The dean passed the idea along but seemed less than enthused. “We still are struggling to teach foundational skills well,” Norton told Meek. Another time Meek alerted the dean that he’d be traveling out of state for a week, but he was “always in contact, however. Know how you look forward to my e mails. … LOL!”

And Meek could dig his heels in to get what he wanted. “I am a stubborn pain in the ass,” he wrote to Norton, in 2018, regarding a deal he was trying to close with the university. But it’s “because I was an insider and know how the system works and does not work.”

The negotiation was over Hottytoddy.com, a news and lifestyle website that Meek created and was trying to give to the university for the journalism school’s students. The deal had nearly fallen apart multiple times, and Norton was caught in the middle. “I have lived a soap opera,” he emailed to an assistant dean.

Still, knowing Meek was advantageous. He recruited students and got them jobs. As the journalism school expanded, it needed more space, badly. Which meant it needed more money, badly. That wouldn’t come from the state. Adjusted for inflation, per-student funding in Mississippi fell by more than 30 percent between the school years 2008 and 2018, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Meek talked up the school and offered a warm hand-off for Norton to potential donors, including a man named Don who was (maybe) about to come into billions and would (maybe) bequeath several millions of those billions. It could be “hot air” Meek told Norton, but “I want to see this through just in case.”

For years, for better or worse, Meek was central to the school’s image and its status. “You have enormous power,” Norton once told the donor. Without Meek and his wife, the school “never would have thrived.”

Soon, that buttress of good will would crack.

On a Wednesday afternoon in September 2018, Meek posted on Facebook two photos of young Black women wearing form-fitting dresses and heels who’d been in downtown Oxford the previous Saturday night. In the post, he cited fights and arrests, declining university enrollment, and complained that property values and tax revenue would “plummet” “if this continues.” The message was coded but clear: These two Black women — or people who looked or dressed like they did — were somehow responsible for the problems Meek identified.

The two women were students. “I’m sitting here like … is he trying to imply that we’re prostitutes? Like, what is he trying to imply?” one of the students said during a public forum. “I deserve to feel secure in my skin on this campus and in this town,” wrote the other student in a guest column in the student newspaper, “just as my counterparts do.”

There was instant outcry. Jeffrey S. Vitter, the chancellor, condemned the “unjustified racial overtone” of the post. Hundreds of students attended an event to share their thoughts. The faculty met several times and soon released a statement requesting that Meek ask that his name be removed from the school.

Publicly, Meek apologized and said he had asked the university to remove his name. Privately, he said the chancellor had given him an ultimatum. “I am not a convicted felon, I am just a convicted fool who made a mistake, one that should not be fatal,” he vented in an email to Norton, which he copied to former U.S. Senator Trent Lott and several other powerful people, though he added that he took “full responsibility for what has happened.”

The dean tried to salvage the situation. “You made a mistake Wednesday, just like I do everyday,” Norton told the donor. “I think you can help us bring people together.”

But some observers, especially those on the right, believed Meek had been treated unfairly. The university faced a firing squad of angry alumni, who swore off donating to an institution that was, in their view, buckling to a progressive agenda, the Mississippi Free Press would report. The chancellor resigned a few weeks later. (He declined to comment for this article.)

In time, Meek seemed to blame Norton and the faculty for his downfall. “Something is rotten in this program,” he wrote on Facebook more than a year later. “There is no fairness or balance,” he wrote, “I know first hand.” He and his wife took back their endowed fund, now worth about $6.4 million. The school also lost out on the Meeks’ estate, worth tens of millions.

The fallout ate at Norton. Meek’s supporters vilified the school as a place rife with “Godless liberals,” reads a document that Norton eventually put together for the new chancellor. Because of this, giving had “declined dramatically.” Those building-expansion plans? Not possible right now.

What hurt him most, Norton confided in some colleagues, was that he had led the journalism school “in a decision that communicated that i am better than Ed Meek.

“I know we had to do it to save our school,” he continued, “but I also know we judged Ed Meek, and we are guilty of similar offenses.”

“Please let me know when I blame others for something, when I have so much to clean up in my own life.”

Meek hadn’t taken the photos himself. He’d gotten them from an acquaintance, Mississippi Today reported. The Free Press would later report that the acquaintance was probably Blake Tartt III, a real-estate strategist and investor whom Norton had been pursuing as a donor, and that Norton had known about Tartt’s role and stayed mum.

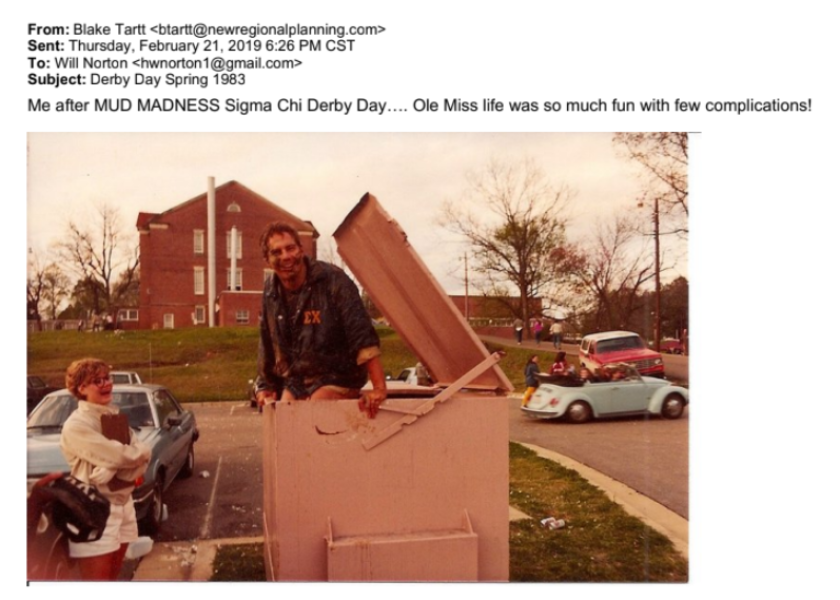

Tartt, a 1984 university alumnus, is president and chief executive of a Houston-based commercial real-estate company that has several properties in Oxford. For years, Tartt had strong ties to the journalism school. At one point he sat on its board of visitors. In 2016, he was profiled in the school’s magazine as someone who is involved with recruiting and job placement for students.

In 2018, there was talk of Tartt helping establish a program at the school that focused on real-estate marketing. He met with Norton and the provost about it a few weeks before the Meek scandal. Tartt also volunteered to help raise funds for a new building for the journalism school. “I am just going to sit back, relax, and help you at the Meek School,” he once told Norton in an email.

Hundreds of emails between them indicate the two were close. They first met when Tartt was a student and Norton a professor. As an adult, Tartt acted as a confidant for Norton, who would vent about the stresses of his role. “This job has aged me severely,” the dean would eventually disclose, “and I am fading.” They talked politics and swapped news articles. Tartt clearly admired Norton. The dean was “the best and my HERO,” the businessman once told Norton.

They were in close contact on the weekend in September 2018 that led Meek to write his fateful Facebook post. They spent time together on game day. The next day, Tartt emailed Norton a video taken at an intersection in downtown Oxford, presumably after the home football game. Students are out enjoying themselves. The camera pans over to a group of Black students and the filmer says, “Goddamn, this is literally like being in the Congo jungle.”

Tartt, through a statement provided by a representative, said that he is not the narrator of the video. It was one among many shared on “a mass chain email” that included dozens of people, that representative told The Chronicle in an email. The police had responded to several fights that weekend. Tartt owns property on the Oxford Square and “was concerned about the effect that reports of violence might have on his business.” He shared the video with Norton to “make a university administrator aware of the problem and to hopefully direct campus police attention to the square after football games.”

Hours later, Tartt sent Norton a picture of a young Black woman wearing a black dress and heels. “I took this picture,” Tartt told the dean. “You know Oxford and Ole Miss have real problems when black hookers are working on Jackson Avenue. The African American visitors from other towns were competing for her affection. It made me sick.

“All may think I am living in the past and not progressive enough,” Tartt continued. “I happen to know what happens when a place is over taken [sic] by the wrong elements. For all the movement for total inclusion,” he wrote, “social engineering does not work.”

Other emails struck the same note. Tartt spoke of fights that had broken out, the “real African hookers,” and said that the “Ole Muss [sic] Culture has been ruined.” Once “a shooting happens they will all wish they never stopped playing Dixie and made up a stupid story about Colonel Reb,” — a reference to the university’s decisions to stop playing the Confederate-forces anthem on game days and to replace its mascot.

He mentioned “gangbangers” and called the new Landshark mascot “a disgrace.” After Saturday’s loss, “I had [to] watch the blind side [sic] to make me feel good about Ole Miss when I got home.”

Norton voiced some general agreement, telling Tartt, who’d complained that what he’d seen on the square was “sad and sick,” that he, too, “really was discouraged on Saturday night” and that it made him “weep what folk have allowed to happen in athletics in town, etc.”

“I think the marketplace will bring about change in Oxford, but it will take a long time,” Norton wrote in another email. “These folk will have to hit rock bottom before something useful will hit.”

“I focus on trying to keep building the Meek School,” Norton said in that email. “But the energy it takes means I cannot concentrate on the ineptitude around me. I make enough mistakes myself. So I keep trying to correct them.”

It wasn’t the first time Tartt had voiced bigoted opinions to Norton. Earlier that month, he had sent the dean a story about Serena Williams showing support for Naomi Osaka after losing to her in an emotional tennis match. Williams “looked like an [gorilla emoji],” Tartt told Norton in a following email. She “simply cheated, then broke her racket and then complained.”

The dean ignored that remark and praised the article, adding, “We need to have mercy and forgiveness.”

To which Tartt replied: “I wish you could have scene [sic] her [gorilla emoji] like behavior. No class. It did nothing to help a [sic] women’s cause.”

Days after Tartt emailed Norton about supposed problems in the square, Meek posted the photo that Tartt said he had taken. Meek told The Chronicle that he’d gotten both photos he posted from Tartt but from other people as well. Tartt called Meek and said he was concerned that “the square was getting out of control and that it left the wrong impression,” according to Meek.

Tartt disagrees with Meek’s “recollection of events concerning the photographs,” says his statement, which added that Meek “independently published the photographs” which were among many others “from many sources shared on group text messages and emails.”

“The fact of the matter,” the statement says, “is that Mr. Tartt is not a racist or bigoted person.”

Meek faced instant blowback. Tartt did not. He was still pursued by the university’s development office. He was appointed to a search committee to find a new chancellor.

Norton seems to have chosen not to disclose what he knew about the businessman’s role in the Meek saga. The two stayed in touch, though Norton reportedly complained to the provost and the vice chancellor for intercollegiate athletics that Tartt had “not contributed to our school despite our attempts to be kind to him.”

Tartt’s role would not be revealed until more than a year later, when first one and then apparently another mysterious group decided to act.

It wanted a lot, including correspondence between Norton and Meek, and Norton and Tartt, and it asked for emails containing many other terms specific to happenings in the journalism school.

Eventually, Transparent Ole Miss received a trove of emails, including Norton’s correspondence with Tartt.

Another group, Ole Miss Information, began sending excerpts of the most-explosive exchanges to faculty members and to reporters, including to The Chronicle. (To verify the emails, a reporter requested them from the university directly.)

Those excerpts reached Noel E. Wilkin, the provost. After validating them, he met with Norton. Wilkin declined to go into detail about what they discussed, but at the end of that meeting, Norton resigned from his deanship, returning to the faculty.

Where some saw capitulation, others saw cowardice.

Neither the school nor the university said anything publicly about the exchanges until after the Mississippi Free Press published a three-part series in August 2020. The stories revealed Tartt’s role in the Meek controversy, detailed many more exchanges between Norton and Tartt, and posited that some university leaders “are seeking to appease the older, whiter, wealthier alumni who pine for the University of Mississippi to return to the glory days of their youth.”

Soon after, Wilkin condemned the “appalling actions and hurtful, divisive comments” described in the articles. They do not reflect “what we expect from members of our university community,” he said in a video. And they “do not represent who we want to be.”

Should Norton have reflected those higher ideals by objecting when Tartt made racist comments? Some professors who spoke with The Chronicle sympathized with Norton, both because of his personality and his position. The former dean, said those who know him, avoids confrontation, and tries to see the best in people. That he didn’t call out a racist message is “part of his persona,” said Charles D. Mitchell, an associate professor of journalism, in an email. “Life has taught him there’s no gain in hating the haters. Change comes through engagement.”

They also pointed to the political realities of Norton’s job: to drum up money and resources in one of the most conservative states in the nation, where progressive dollars aren’t exactly a renewable resource. If university officials were to ask donors what they think on the subject of race before accepting money, “your receipts are going to go down dramatically,” said Bill Rose, a former faculty member and a friend of Norton’s. “That’s just a fact of life. It’s sad that that’s true. You could even say, That’s not right. But it’s a cold hard fact of life for universities who are strapped for cash all over America.”

Still, where some saw capitulation, others saw cowardice. That Norton tolerated Tartt’s language was for many faculty members a shock and a disappointment. (The Chronicle spoke to 18 current and former faculty members for this article.) In 2018, while the university was reeling from Meek’s Facebook post, Norton appeared in a video, backed by faculty members, and echoed the then-chancellor’s condemnation. For him to do that “knowing full well that all the information hadn’t been revealed” was hypocritical, said Timothy Allen Ivy, an adjunct instructional assistant professor in the school.

And Norton’s conduct spoke to problems that went beyond just one dean, some thought. Ellen Meacham, an adjunct instructional assistant professor, pressed the interim dean and other university leaders for answers. She wanted to know what policies were in place for vetting donors, if the development office was guided by any code of ethics, and what, if anything, would change. (Wilkin, the provost, told The Chronicle that when he and others meet with potential donors, they’re always looking for “mission alignment” — finding opportunities where “what we can do as an institution aligns with things that they think are important in the world.” That alignment is ensured through multiple checks, Wilkin said in an email, like through the university’s naming committee, which reviews proposals to name buildings or units before they’re sent up the chain.)

“I often get the impression,” Meacham told administrators in an email, “that our university leadership and fund raisers think they are at the mercy of some of these powerful forces because of money. But that does not have to be true.”

“I want to see UM campaigns that say and keep on saying, ‘This is who we are,” she said. “This is what we stand for. We invite you to be [sic] join us, but this is also what we will not tolerate. If you are for us, then give. If you aren’t, then BE ON YOUR WAY,’.

“I refuse to believe,” Meacham wrote, “that this is too much to ask.”

What Meacham understood is that resources are never given or solicited in a vacuum. Universities are sites imbued with meaning. The University of Mississippi’s is a live question. For years the institution has taken steps to distance itself from Confederate symbols and to contextualize landmarks, to demonstrate to Black students and employees that they can feel safe and supported on campus. A sector of alumni and conservative politicians, and some students, meanwhile, have repudiated those decisions.

It’s clear what version of the university Tartt believed in.

In an email to Norton, he reminisced about “bright memories” from his college days. “It was truly a great time at Ole Miss and Oxford.”

But now?

“Lame out-of-state liberals, punk spoiled rotten millennials, and racist faculty members have totally ruined what was the greatest place on EARTH!

Nothing last [sic] forever. … The money will dry up. Those who tore the traditions apart will have no memories and realize how great the sound of DIXIE was when they can’t put food on the table.”

That sparked some resistance in Norton. The version of the university that Tartt remembered, and the one he was describing now, were both fictions.

The dean told the alumnus: “You just do not know this campus.”

“We walk among you and work side by side with you,” the website says. “We love Ole Miss and want it to thrive. The secrets are killing us.”

Before the Free Press series ran, Ole Miss Information sent around excerpts of the most egregious exchanges between Norton and Tartt and implored faculty members in the journalism school to take action. (The emails are often blind cc’d so it’s not possible to know who all received them.)

Norton “hid this from everybody.” The dean had sympathized with Tartt. “If you want to stand beside that man rather than the truth go ahead,” the group wrote in April.

In July, the tone intensified: “Truth is our shibboleth! We are not bots. We all drink from the same cup. … Fear need not be a yoke suppressing action. Join us in revealing the truth. When the lies are no longer hidden all of us will breath [sic] free.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the call to arms fell flat. For one thing, everyone was dealing with the burgeoning Covid-19 pandemic. Some say they didn’t pay much attention to the emails. They were put off by the melodramatic rhetoric or the group’s anonymity, or they thought the messages were spam. It probably didn’t help that the group sent them from Yandex Mail, a Russian email service, and signed off with various character names from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four: Winston Smith, Emmanuel (or Manny) Goldstein, or Julia Dixon.

At least a few professors saw problems with the Free Press series. They questioned the outlet’s editorial choices and thought that not enough faculty members had been contacted. (Donna Ladd, the editor, responded to those criticisms and explained the outlet’s decisions in an editor’s note.) On August 6, 2020, the day after a faculty meeting, Ole Miss Information criticized professors for trying to figure out who was contacted by the Free Press. “Don’t pretend asking ‘did they call you?’ is anything appropriate to ask or anything other than an attempt to identify who spoke. Nice look for a j-school,” reads an email, signed by “Winston Smith.”

What Ole Miss Information wanted, it would say, was a “supportive and vibrant school with robust shared governance.” Its soaring rhetoric could at times sound naïve. It said it had raised concerns through other channels at the university that had gotten nowhere, and it insisted that anonymity was the only way it could act.

Some in the school wondered about the group’s endgame. It fixated on Norton, who’d resigned from his deanship months before and kept a salary the group felt was way too high. “Will hurt us all,” reads a September email from the Ole Miss Information, “and now he is laughing all the way to the bank.”

Someone “with an ax to grind” decided to take it out on this school and “in the age of easy anonymity had a field day,” said Mitchell, the associate professor, in an email. The First Amendment, he noted, does not require a critic to self-identify. But anyone “sincerely interested in fomenting progress,” he wrote, “would seek conversation instead of tossing grenades.”

To be sure, at least a few faculty members felt that Ole Miss Information had raised some legitimate concerns. But eventually, even they felt the group had veered into personal attacks and undermined the journalism school.

The group’s most intense public criticism was lobbed at Alysia Steele, an associate professor in the journalism school who had strongly criticized the Free Press series when it ran. She pitched a column about her perspective to Poynter, a media research organization. In the midst of going back and forth with a Poynter director about the essay, she got an email from Ole Miss Information with the subject line, “Poynter hit piece.”

“If this is how low jnm [Journalism and New Media] has sunk,” the email said, “we are even worse than under Norton. … What a sorry excuse for ethics,” it concluded, “and what a magnet for a defamation suit.”

The email jarred her. Steele had told few people about the essay. Poynter decided not to publish it, so Steele posted her essay on the web site Medium.

Days later, a Facebook page affiliated with Ole Miss Information called Steele’s piece “poorly written and error ridden.” If Steele’s writing “is a reflection of the quality of the Ole Miss journalism instructors” then students “are being ill served.” And “Mrs. Steele” “lacks the qualifications to hold her current job. In fact she lacked the qualifications to hold her previous nontenured assistant-professor position.”

To have her credentials called into question was demoralizing and insulting for Steele. Before arriving at the university, Steele, a decorated photo and multimedia journalism, had been part of team that won a Pulitzer Prize and is working to get her Ph.D. The public attacks, said Steele, who is Black, felt “like Jim Crow,” like someone was telling her to “know your place.”

The group wrote other personal criticisms, including of Debora Rae Wenger, the interim dean, on Facebook; and of Patricia Thompson, an assistant dean and assistant professor, on its website. In a Facebook post, the “Winston Smith” group listed associate and full professors who do not hold Ph.D.s and said they’d been hired or promoted into positions they weren’t qualified for, which was an “astronomical waste of taxpayer money.” In another post, Winston Smith bemoaned how programs that “water down faculty credentials” to the level of a community college should “not expect broad support from campus faculty with Ph.D.s and where rigorous peer reviewrd [sic] research is valued.”

That struck Joseph B. Atkins, a professor of journalism, as unfair. “What decent journalism program in the country does not at least have some faculty members who do not have a Ph.D.?”

The group had also reported ethics violations to question faculty competence and credentials, Wenger said in an email. “In every case, those allegations have been found to be without merit,” she said, but the pain for the faculty members involved has been “palpable and damaging.”

Black and international faculty members, in particular, felt targeted by Ole Miss Information. Many Black colleagues have been made to feel a “great deal of pain, fear, and distraction,” Meacham later wrote to the faculty. (Most of those faculty members did not respond to The Chronicle’s interview requests.) By late September last year, seven people within the school had formally complained that the work environment had become hostile. In early October, a majority of the tenured faculty members voted to submit a grievance letter to Wenger and to the university’s office of human resources.

The emails and posts have “increasingly created a chilling effect on faculty speech, dampened faculty collegiality, interfered with teaching and scholarship, and caused several to express they feel they work in a hostile environment,” reads the letter, backed by 12 faculty members. Later that month, Provost Wilkin assured the school that action was being taken. In response to the hostile work environment complaint, the Office of Equal Opportunity & Regulatory Compliance had opened an investigation.

News of the grievance letter only pushed Ole Miss Information further into its corner. Anonymous commentary, it wrote in an email, “has always been a powerful and legitimate tool for expressing dissent.

Agree with us or not, but do not accuse us of acting inappropriately.”

As the equal-opportunity office’s inquiry got underway, people in the school suggested someone they thought might be involved: Paul J. Caffera, the university ombuds. Why? It’s unclear. Some thought he had a relationship with a faculty member who had longstanding problems with Norton, and who was suspected to be behind or involved with Ole Miss Information.

Neither Caffera nor the equal-opportunity office responded to The Chronicle’s interview request. Nor did Gene Rowzee, who was then the office’s interim director.

In a November meeting with Caffera and his lawyer, Rowzee told them that there is a “belief among some of the folks” in the school that Caffera “may be causing or contributing to this hostile work environment” and that he may be using his office “to pursue a personal grudge for a friend or an intimate,” according to an account of the Zoom meeting.

In that conversation, Rowzee also said that while he had not obtained Caffera’s emails, if he got into a situation “where nobody is talking to me, then I have to go where the investigation leads me.”

By that point, Caffera had also been contacted by an investigator from the university’s police department who was also looking into the issues at the school, which, Caffera’s lawyer would later argue, was a “frightening escalation of the university’s approach to this situation.” Shortly after his meeting with Rowzee, Caffera went to court. He sued the university, claiming that he was doing so to stop the institution from compelling him to release confidential information.

In court documents, he said that he was not the author of any anonymous emails or social-media posts or affiliated with any anonymous group. The allegation that he was “abusing my office” on behalf of “a friend or intimate” was false, he said in a sworn affidavit. Caffera’s lawyer disparaged the equality office’s investigation, arguing that it was “based on just a vague and unprovable belief — a hunch.”

And, the lawyer said, the ombuds was being retaliated against. “It has long been clear,” his lawyer argued, “that certain leaders and other persons within the University’s School of Journalism and New Media have harbored enmity towards Caffera because of his faithful performance of his job.” (Both Wenger and Wilkin declined to comment on the litigation.)

Lawyers representing the university argued that Caffera was “creating nonexistent concerns and raising false alarms,” and asked the court to “disrupt an internal university investigation by immunizing him.” Under “the guise of protecting other employees,” Caffera was asking the court to intervene in the university’s ongoing personnel investigation regarding allegations of his misconduct. Therefore his “real aims,” they argued, were “to protect his own personal employment interests.”

Essentially, they argued, the university got a complaint about him, and now it had to investigate it. Employment policies “apply to him just as they apply to all University employees.”

While this played out, Caffera was put on leave, which alarmed many faculty members outside of the journalism school. He was reinstated in March, and both he and the university agreed to dismiss the case.

As for the investigation, after interviewing some 30 people, Rowzee concluded that the environment within the school was indeed hostile, and that a disproportionate amount of the harassment was directed toward people of color and international faculty members.

But his office couldn’t figure out if anyone affiliated with the university was involved. An email to his university account provoked a bounce-back message: He’d be leaving the office in June and would “not be returning.”

Within the journalism school, the atmosphere for some has changed. People talk less in faculty meetings. Though Steele has been able to sustain her work, she finds herself closed off from those around her. She’s in “this weird space,” she said, of not wanting to share her scholarship with her colleagues, of not wanting to let them into her life.

“I’m just a shell of the person I was before I came here,” she said.

The school has begun to grapple with the questions that Norton’s exchanges originally put on the table. Interim Dean Wenger announced that the school would schedule more training for faculty and staff members on what it means “to be anti-racist and to be allies for those who have felt excluded in some way.” It would overhaul its diversity plan, which has been in place since 2011. It developed and adopted gift-acceptance guidelines for the school to work with donors.

“This is an ongoing conversation,” Wenger said in the statement, “and we are listening.”

The reality is that fund raising for a modern research university is like breathing. It’s natural and constant. If state funding continues to decline, the university will look to donors and other sources to make up the deficit. But administrators “shouldn’t have to sort of tap dance with racist donors to try to get support for the university or the program,” said Professor Atkins. “And if their racism is part of that whole chemistry, I mean, then let them go. Forget them. Go to more enlightened donors.”

“Even if that’s tough,” he said, “that’s what you’ve got to do.”

The gift-acceptance guidelines, a one-page document, establish a donor-relations committee that will review the details of potential private gifts of $100,000 or more and make recommendations to the dean. When seeking gifts, the school will consider, among other things, “compatibility — how the intent of the donor matches the school’s use of the gift” and “mission — how the acceptance of the gift aligns with the mission of the school.”

Those are the ideals. How feasible they are to uphold is another question. It’ll be something for the new dean to figure out. The former dean was ground down by the dance he had to do with alumni and those outside the school. (Norton stepped down from the faculty in May.)

People who love the university “do not love the job my colleagues and I are doing,” Norton once wrote to Tartt. Alumni, Norton believed, define what an institution is. And the alumni’s notion of what the University of Mississippi should be differed from Norton’s.

They want a “propaganda machine for the right wing,” Norton wrote. A few people on the left have “said some stupid things in response” which has made “the decline of the university even more unhappy.” He was tired of being caught in the middle.

So he was stepping back from public life. “I gave it all I had for 10 years, and I am going to give it all I have for the rest of my term, but I am no longer socializing,” he told Tartt. The practice “does not bring the benefits to our school that I am supposed to bring to it.”

He no longer had the stomach for it.

[ad_2]

Source link