Nebraska Regents Vote Down Resolution on Critical Race Theory

[ad_1]

A majority of regents at the University of Nebraska on Friday did not back a resolution that said critical race theory should not be “imposed” in curriculum, training, and programming.

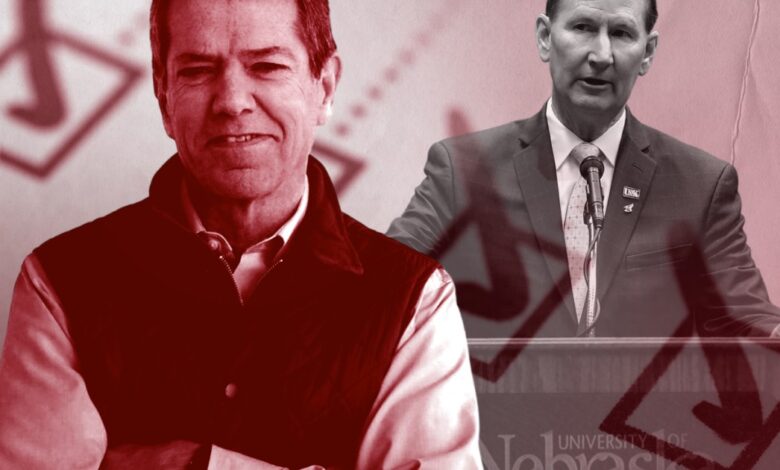

Five of the eight elected regents voted against the measure, which had been proposed by one of the board members, Jim Pillen. Pillen’s resolution also claimed that critical race theory “seeks to silence opposing views and disparage important American ideals” and that it “does not promote inclusive and honest dialogue and education on campus.”

Critical race theory is an academic framework that interrogates the relationship between race and racism and American legal systems. It has been depicted in conservative circles as anti-American and discriminatory, and has become something of a political football.

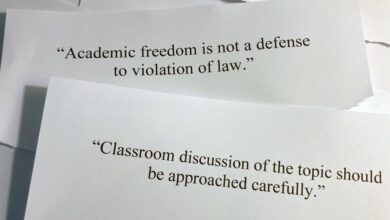

The university system’s faculty senates, student governments, and campus leaders were against the proposal. On Friday a majority of those who spoke during the public-comment portion of the board’s meeting opposed the resolution, calling it a threat to academic freedom and a “gross overstretch of authority.” They said Pillen — who is also a Republican gubernatorial candidate — was giving in to the “puzzling national hysteria” over the academic concept to cater to voters. Several students of color spoke about the importance of discussing topics of race and racism in the classroom.

During the meeting Pillen said his measure had been mischaracterized. It “does not ban the dialogue of CRT for students that seek it out on an elective basis.” Rather, “critical race theory should not be forced on our students and staff as an unquestionable fact. They should be free to debate and dissent from critical race theory without fear of silencing, retribution, or being labeled. They should also be free to avoid the concept of critical race theory altogether without penalty, if that’s what they choose.”

But those conditions, university leaders said, are already being met. Taking a course in critical race theory is not a requirement to graduate, Ted Carter, the system’s president, said at the meeting. He previously told The Chronicle that there is already a process through which students can complain if they feel they cannot express their views freely.

“We don’t impose ideas,” said Mark Button, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, during the meeting. “We assign them in order to critically evaluate, discuss, and debate them.” Button also told the board that he’d heard from program directors that several tenured and untenured faculty members of color were beginning to look for positions at other institutions. “This type of self-inflicted loss of competitiveness,” he said, “will hamper the great strides that we are already making in establishing the University of Nebraska as unparalleled among public research universities.”

Ultimately, Pillen was joined in his yes vote by two regents, Robert Schafer and Paul Kenney. Classrooms should be “a free marketplace” of ideas and thoughts, but at the same time, nothing “should be forced or thrust upon someone,” said Schafer.

Elizabeth O’Connor, who voted against the resolution, said that it’s “not the job of the university to teach that the world is fair, and that race doesn’t matter.” (A portion of Pillen’s resolution said that America is “the best country in the world” and that “anyone can achieve the American Dream here.”)

“It’s the job of the university to teach about the world the way that it actually is,” she said.

Timothy Clare, who also voted against the resolution, did so in part because it violated the board’s bylaws, he said. “Our role as a board is one of governance, not management, and I believe this resolution crosses that line.”

“Simply put,” he added, “this proposal is a solution looking for a problem and will no doubt create more problems than it solves.”

[ad_2]

Source link