An Admissions Process Built for Racial Equity? This Report Imagines What It Would Look Like

[ad_1]

Ditch the ACT and SAT. End early decision. Abolish preferences for legacy applicants now.

Critics of the admissions process have long demanded such changes in hopes of making the system more equitable for students. Over the last 20 years, a slew of proposed reforms have typically had two things in common: They (a) urged highly selective colleges to stop doing something, and (b) focused on a specific policy or practice in isolation, even though one discrete change alone — like, say, going test-optional — doesn’t automatically guarantee more equitable outcomes at a given college.

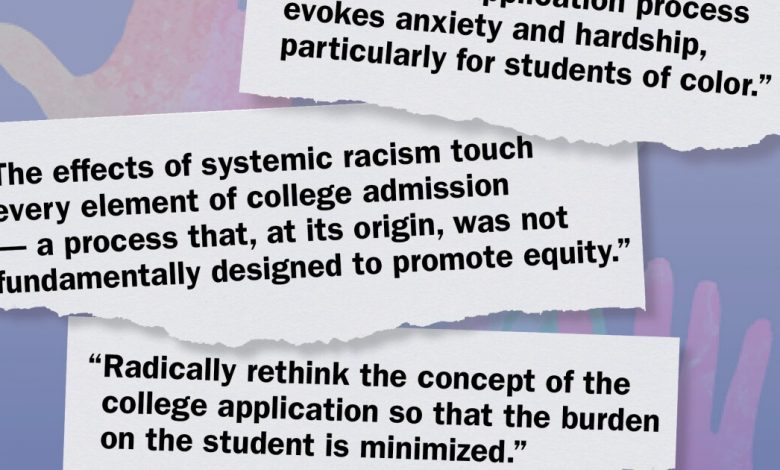

A report released on Wednesday by two prominent associations takes a broader view of what’s wrong with the admissions and financial-aid system by examining the complex process through the lens of racial equity. “The effects of systemic racism,” the report says, “touch every element of college admission — a process that, at its origin, was not fundamentally designed to promote equity.”

That last part is key. The admissions realm, forever talking up its lofty ideals but forever entrenched in the relentless competition for revenue and indicators of institutional awesomeness, is a system at odds with itself. But it does, more or less, what it was built to do.

Though no set of bold-type proposals is going to transform the profession, the report offers numerous recommendations for institutional leaders, as well as state and federal policy makers. The report argues that existing admissions and financial-aid processes can be rebuilt to better serve racial minorities, especially Black students. The question: What would those systems look like if promoting racial equity were the main objective?

The report, financed by the Lumina Foundation, was produced by the National Association for College Admission Counseling and the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators. Its findings and recommendations were drawn from interviews with a panel of more than 20 admissions and financial-aid experts, as well as recent college applicants.

Here are five key ideas from the report:

Examine the consequences of selectivity. Given the effects of systemic racism and the “inequitable system of inputs” the admissions process relies on, the report says, selective colleges should examine why they exclude applicants. That is, which subgroups of students their policies and practices tend to leave out: “Institutional awareness of who is likely to be excluded is essential to an understanding of racial inequity.”

Admissions officials should assess whether they could serve institutional goals with selections processes that minimize the effects of racial inequities. And institutional leaders should look for ways to “reconcile institutional prestige and equity goals.” One expert quoted in the report boiled it down to a choice: “Either you redesign the whole institution around equity, or you don’t.”

Simplify the application process. The more complex an application is, the more inequitable it is. Institutions, the report says, “should radically rethink the concept of the college application” to ease the burden on students. The current process “evokes anxiety and hardship, particularly for students of color” (and those who lack access to a school counselor or knowledgeable guide to help them).

A student’s performance in school “should be the nearly exclusive focus for taking the step to postsecondary education.” Colleges, the report says, should seek ways to incorporate more-nuanced assessments of applicants’ high-school performance, and consider minimizing or eliminating external assessments and additional requirements. “We still require them to fit this very traditional box,” one panelist said, “even though we say that we want nontraditional student to be part of higher-education spaces.”

Furthermore, admissions offices should help create a way to simplify and automate the transfer of student information to colleges in which students have expressed an interest. Colleges should either reduce or eliminate application fees — and make fee waivers widely available and easy to obtain.

Further streamline the federal-aid process. Colleges should ensure that their financial-aid materials include a notice that applicants may file their Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, as early as October 1, which would give them more time to locate documents they might need if selected for verification — and more time to make an informed college choice. And colleges should strive to get aid awards to students sooner.

The report urges Congress to codify the October 1 release of the FAFSA into statute. It also asks the Education Department to extend the 2021-22 verification waiver, which has reduced a major hurdle for many disadvantaged applicants. “Low-income and vulnerable students, who are most burdened by verification, have borne the brunt of this pandemic,” the report says, “and not renewing the verification waiver will make the college-admission process that much more difficult.”

Diversify the admissions profession. Enhancing the racial and ethnic diversity of admissions staffs, the report says, can increase an institution’s ability to “attract and relate to a diverse student population.” Colleges should prioritize racial equity in hiring and retaining admissions officers; conduct antiracism training for staff members; and hold listening sessions with current and prospective Black students, whose feedback could inform their recruitment practices.

Colleges should also take a close look at their prompts for essays required for admission and scholarship applications, especially those concerning challenges they have overcome. Some students who participated in the research said they felt that colleges expected them to fit a particular profile, by describing their hardships and struggle. One asked why “minority students have to showcase this resiliency like they are superhuman in order to get into college?”

Confront implicit bias in financial-aid offices. Financial-aid leaders should examine the extent to which implicit biases might affect their aid processes, including the case-by-case decisions officials must make when students appeal their aid awards. Colleges should consider how much rigorous academic requirements for scholarships “can be inherently inequitable for low-income students, who are disproportionately students of color” — and who might have experienced numerous challenges, attended high schools lacking rigorous curricula, and balanced family obligations with their schoolwork.

The report, “Toward a More Equitable Future for Postsecondary Access,” is less a long list of specific prescriptions than an urgent call for a reckoning with history. The admissions process as we know it wasn’t handed down from the clouds; it grew out of entrenched systems that have long worked against disadvantaged students.

As such, there are some serious caveats here. One: Many of the proposals go beyond the purview of admissions and financial-aid officials, who, the report says, “are often structurally confined from making the changes that they know need to be made to make higher education more accessible and equitable.” As powerful as those gatekeepers might seem from a distance, they can’t fix inequities in elementary and secondary education, or rewrite state and federal policies.

Also, all the admissions reforms in the world probably won’t help the many students who lack sound college advising — or any at all. The report urges postsecondary institutions to play a larger role in the professional development of school counselors and college advisers.

Angel B. Pérez, NACAC’s chief executive officer, has often said that many substantial changes in admissions probably can’t happen without a major overhaul of how higher education is financed, for starters. But he has cautioned admissions officials against throwing up their hands in the meantime. The report, he told The Chronicle, “opens the doors for leaders, institutions, policy makers, and NACAC, among other associations, to ask somewhat radical questions and make moves towards change.”

NACAC, Pérez said, plans to take up the report’s recommendations for cultivating diversity among the next generation of admissions officers: “If the profession is to thrive, and we are to attract more students of color to college, the profession must also be representative of our students today.”

Changing the way a big, complicated, hidebound system works isn’t easy. One reason, the report says, is “the tendency to assume that the system’s current design is fixed or a ‘given.’”

[ad_2]

Source link