‘The Biggest Mess’

[ad_1]

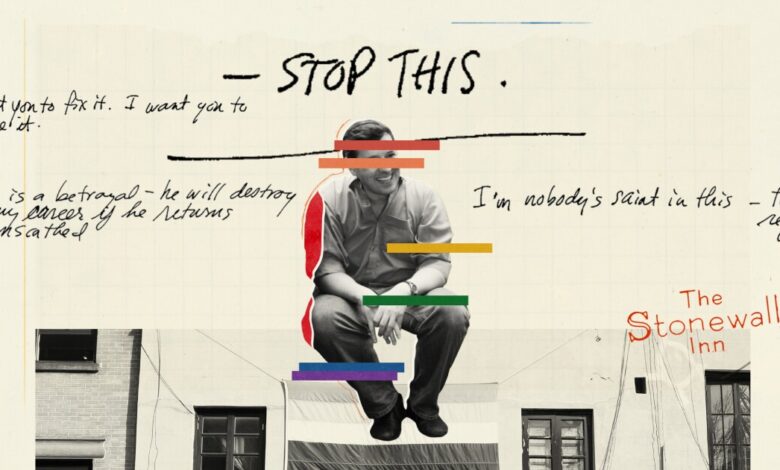

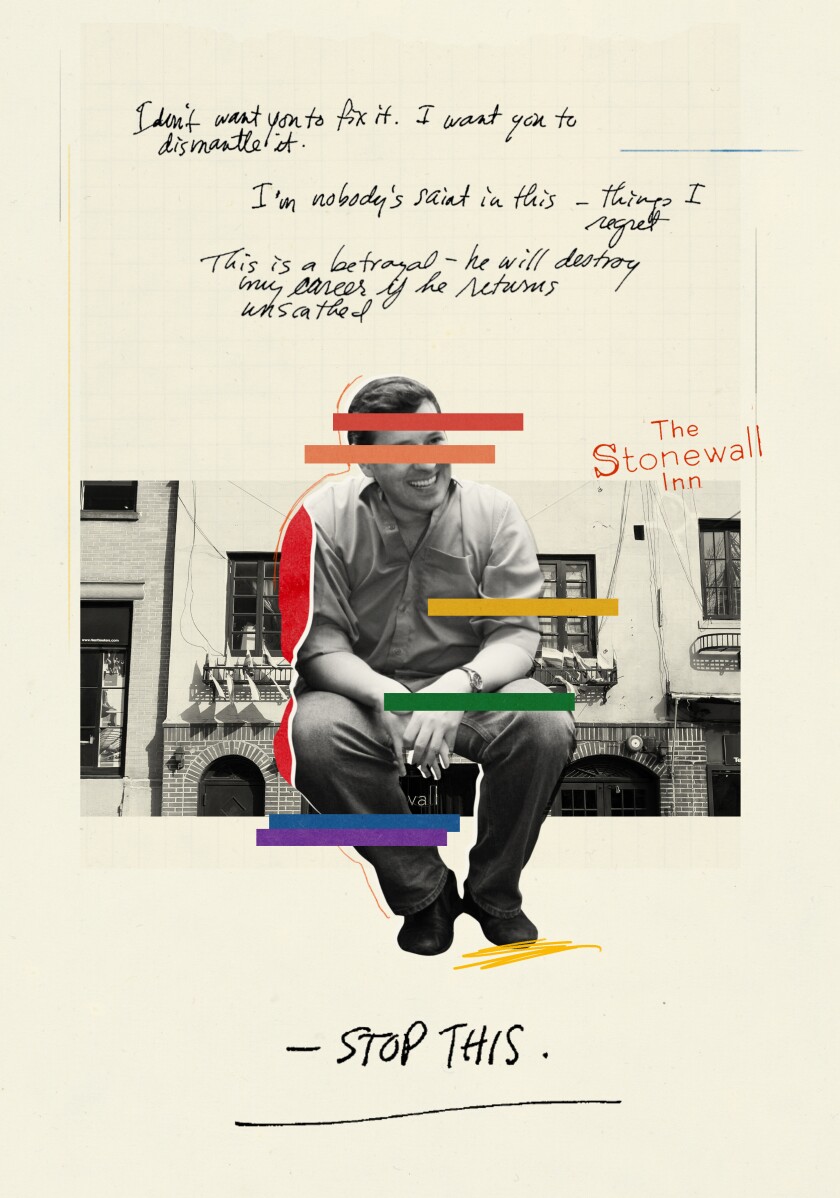

As a tray of liquor shots circulated around the party at the Stonewall Inn, an iconic gay landmark in New York City, Kelman watched while Parsons laughed with his colleagues from the HIV-research lab he directed. At the time, Kelman had worked for only a couple of weeks at the Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies and Training, known as CHEST. What little she knew of Parsons had come from her new colleagues, who had described the director as tempestuous and quick tempered, known to berate subordinates in the middle of the office.

But here, on May 4, 2018, Parsons appeared to be in his element, soaking up the raunchiness of a night that promised lewd humor, a drag-queen emcee, and serious drunkenness. This was “CHESTFest,” an annual bacchanal in honor of the center, which was affiliated with the City University of New York’s Hunter College, where Parsons was, at that time, a 51-year-old distinguished professor of psychology.

CHESTFest’s reputation preceded it. Kelman had heard from her coworkers about the previous year’s celebration: A booze cruise through the harbor with shirtless male dancers and, she had been told, hard drugs. The culmination of these events was when Parsons, as sole judge and jury, determined who was most inebriated and anointed that person with the title of “The Biggest Mess.” Strictly speaking, CHESTFest was optional. But Parsons was prone to ridiculing those who skipped it, and the party was considered the main staff bonding event of the year.

Even in her short time at CHEST, an organization of about 45 employees, Kelman had a sense that a lot about the management of the center and Parsons was off. She had recently completed a master’s degree in public health at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, only to find that her peers on the junior staff for the most part had little formal work experience outside of the insular world of CHEST and had mostly been promoted from within.

As a project coordinator on one of Parsons’s grants, Kelman worked for him, although he was not her direct supervisor. Before CHESTFest, though, she had yet to meet the director. When they finally did meet that night, he greeted her with a question: “Which one are you?”

Parsons had founded CHEST in 1996, building over the subsequent two decades a mighty cash cow that brought millions of dollars in grant money to the university. The federal grants that fueled CHEST had established Parsons as a seemingly untouchable sovereign in a vast university system that tended to give the professor what he wanted.

As became clear to Kelman that night, what Parsons wanted was a debaucherous celebration that teetered constantly on the border of impropriety. During a karaoke competition at the party, Parsons approached an employee onstage and unbuttoned the man’s pants, Kelman and other witnesses said. During another song, the professor lifted an employee’s shirt, to the person’s visible shock and embarrassment. It was a record-scratch moment that brought the festivities to an abrupt conclusion, Kelman recalled. The victim fled the Stonewall in tears, running to the street, where colleagues tried to provide consolation.

Bryan Thomas for The Chronicle

That was the beginning of the end of Parsons’s career at CUNY. Before long, the CHESTFest debacle would cost Parsons his job and his lab, and leave a lasting stain on his reputation. So too would it extinguish any lingering possibility that the university, which had benefited so handsomely and for so many years from Parsons’s research largesse, could any longer look the other way.

Stunned by what had transpired, Kelman retreated with a few coworkers to a nearby diner. Later, she texted a friend, writing, “There was a very visible sexual assault at the end of the party on Friday, so there’s a giant organizational reckoning happening.”

“The director is toxic AF,” she added. “Like, a straight up bully, verbally abusive to senior staff and mean to everyone else.”

What Kelman didn’t fully realize at the time was that this episode had been many years in the making, and something like it was entirely foreseeable. A Chronicle investigation has identified a host of red flags and complaints about Parsons and CHEST that failed to inspire anything resembling a meaningful investigation or apparent intervention. In the decade leading up to that night, at least six people had elevated concerns about Parsons to human-resources officials or to faculty leaders. But in no case did complainants ever hear back, they told The Chronicle. Meantime, top Hunter officials continued to sign off on raises, promotions, and new perks for Parsons. (In 2017 he earned $363,282.)

It was only during the fallout of the 2018 CHESTFest, when the university appeared to have no other choice, that an inquiry involving witnesses from across the organization’s history took place. In its wake, CUNY reached a legal settlement with some of the professor’s accusers, restricting what they can say about the case.

This account is based on more than 1,000 pages of public documents and interviews with more than two dozen people who worked with Parsons over the course of two volatile decades. Many of the sources who spoke with The Chronicle said they were reluctant to revisit what they described as trauma. Some said they feared that Parsons, even in his diminished professional state, had the power to damage their careers by torpedoing grant applications or badmouthing them to employers. For these reasons, The Chronicle has in several cases agreed to grant sources anonymity. The story they tell about Parsons, and CHEST, and the system that enabled him, is consistent and specific: Jeff Parsons’s behavior was no secret, and anyone who didn’t know about it could easily have found out.

The recruiter’s job was essential to the CHEST operation. For many of its studies, CHEST needed gay men, who were active in New York’s party circuit, to tell them about their sex lives, their drug use, and, if they were HIV-positive, how they managed — or failed to manage — taking their medications while high on cocaine or other club drugs.

CHEST got its start around the beginning of Bill Clinton’s second term as president, just when big federal money was starting to flow toward HIV-related research. Parsons, who is gay, was in the right place at the right time to capitalize on two things: Authorization of the breakthrough “cocktail” of antiretroviral drugs to treat HIV, and a liberal shift in national politics. Seemingly overnight, an area of research that had been politically poisonous was becoming more viable.

On one memorable night, the recruiter was invited to hit a bar with Parsons, who was participating in an outreach effort known as the Drag Initiative to Vanquish AIDS. The DIVAs, as the group’s members called themselves, would dress in drag and throw condoms around bars, conveying a jovial message about practicing safer sex.

The recruiter had hoped to advance within CHEST. He wanted to be more involved in research, and he thought that getting close to Parsons on a DIVAs outing might help. But he didn’t fully understand what that would mean. After entering a bar, he was taken aback when Parsons stopped to perform oral sex on a patron, the recruiter said.

The recruiter said he could not recall the name of the bar. But he remembered it as a typical gay bar — not a sex club. Parsons was sending a message about CHEST to everyone in the room, the recruiter said: “We are delicious here.”

The recruiter remembers being frightened and shocked. “In a low-level way, it felt like walking in on my parents. But it also felt like he was a monster. It felt like he was not safe.”

“I felt scared,” he added, “that he was … that there were no boundaries.”

In an interview with The Chronicle, the recruiter’s husband said that he recalled his then-boyfriend, with whom he lived at the time, telling him about Parsons performing oral sex in the bar. He also said he remembered what his boyfriend told him had happened next.

Hoping to impress his boss that night, the recruiter froze when, he said, Parsons directed him to perform the same sex act on someone in the bar. “He pressured me to give this guy a blowjob, and I didn’t want to,” the recruiter said.

Bryan Thomas for The Chronicle

Parsons declined to be interviewed for this article, and he did not respond directly to a detailed description of the incident with the recruiter or other allegations included in this report. In a statement, Jeffrey Lichtman, Parsons’s lawyer, wrote, “From what we’ve been able to ascertain, much of the allegations are from disgruntled former CHEST employees.”

Parsons has not been charged with a crime, and Lichtman added that “should any civil action be brought relating to these claims we look forward to defending against them inside a courtroom.”

The recruiter was, at that time of the incident, an out gay man in his late 20s. But he had grown up feeling he had “this disease called gay.” As a teenager, he had spent memorably regretful sessions with a psychiatrist whose job had been to talk him out of being homosexual. Parsons, in contrast, celebrated rather than pathologized the desire to have sex with men. In the bar that night, though, the recruiter was overwhelmed by a sense that Parsons’s version of gayness was horrifying and wrong.

“Suck his dick,” the recruiter said he remembered hearing Parsons say.

He tried to resist. He made light of the pressure.

“I remember saying, ‘I don’t want to, ha ha.’ Like trying to be cute in resisting, but really not wanting to,” the recruiter said.

To get out of the situation, the recruiter said, he finally gave a quick smooch to the man’s penis. “I was not forced, but I was definitely pressured into it by Jeff,” the recruiter said. “I don’t know that he knew how much I didn’t want to do it.”

Another former CHEST employee was in the bar that night, the recruiter said, but the recruiter was unsure if his colleague had witnessed the incident. Contacted by The Chronicle, the former employee said that he did not remember the specific episode but that he had heard Parsons boast about performing oral sex in public spaces.

The recruiter did not consider in the moment that the incident might constitute sexual harassment, although he remembered feeling guilty about what had happened. Months later, the recruiter quit CHEST to take another job, having worked at the lab for less than two years. Apart from his husband, he had, until now, never told anyone what had happened. Others did tell what had happened to them, though, and no one with the power to change it appeared to take serious action.

“He’s one of those people who knows that he is not palatable,” the student said of Parsons. “And so he waits until you’re embedded enough that he feels like you owe him or you’re not going to leave. And all of a sudden he reveals who he really is. It’s pretty much like Bram Stoker’s Dracula.”

The student recalls the precise moment when the scales fell from his eyes. Another Ph.D. student in Parsons’s department had a congenital limb deficiency that caused her fingers to be fused together. At a meeting where the woman was not present, the student said, Parsons referred to her as “Dolphin Girl,” a comment the student found stunning in its cruelty.

Over time Parsons’s inhibitions around the student eased. One summer, Parsons hosted a pool party at his house in New Jersey, bragging that the bartender he had hired was a porn star, the student recalls. As the student lay on a float in the pool, Parsons stopped to compliment his butt, the student said. Parsons would frequently talk about “how hot” certain CHEST employees or study participants were, the student said. He would rail, too, against anyone who left the center, which he saw as a betrayal. “I hope she’s happy teaching community college,” the student recalls him saying of a departing colleague. “That’s all she’ll ever do.”

Then there were the drugs. The student said he saw Parsons snort cocaine once in his office before a DIVAs event.

I felt scared that he was … that there were no boundaries.

“He felt immune,” said David S. Bimbi, one of Parsons’s longest-serving colleagues, who said he also saw Parsons use cocaine. “He operated that office like his fiefdom. If he wanted to do lines of cocaine on his desk, this is his office, this is his world. His ego got bigger and bigger and bigger. It just got crazy.”

By the spring of 2010, Parsons was building CHEST into an empire — and he was throwing his weight around at Hunter College. Parsons was bringing enormous amounts of money into the college’s psychology department, he said in an email to a top administrator, and yet he had to grovel for his share of it.

“I need a deputy chair for next year, or I seriously will resign,” Parsons wrote to Vita C. Rabinowitz, who was provost at the time.

Rabinowitz acquiesced. “You can certainly have a deputy chair,” she responded. “The department is in every way large and complex enough to deserve that.”

In the fall of 2011, Parsons sent another email to Rabinowitz, this time about the “space crisis” at CHEST. Parsons complained of being “seriously at my wits end” about space constraints and “tired of spending my sabbatical NOT writing as was intended.”

In response, Rabinowitz wrote: “I understand and I am beyond sorry. You don’t deserve this.”

That year, the center brought in $4.3 million in federal grants, a CHEST grant history shows. Not only was the center flush with cash, but its physical space — a few miles from Hunter College — meant that Parsons’s employer had little occasion to observe the day-to-day operations at CHEST. No one seemed to be watching the center, for instance, when an employee got so drunk at an office party that he had to be taken to a hospital, several CHEST sources said. (The former employee did not respond to interview requests.)

Who was responsible for Parsons? Who was responsible for CHEST? The byzantine administrative structure of the City University of New York makes that question more complicated than one might think, and most employees at CHEST weren’t coached on the nuances. Parsons was employed by Hunter, but most of his subordinates were employees of the Research Foundation of the City University of New York, which manages grants for all of the university’s campuses. He also had a doctoral appointment at the CUNY Graduate Center, an independent campus where most of the university’s doctoral programs are based, and where the graduate students who worked at CHEST took their classes. Employee complaints could have gone to any of these entities, and it is not clear if they communicated with one another when people reported Parsons.

When the graduate student whom Parsons had mentored finally quit, he reported his concerns to Michelle Fine, a distinguished professor of psychology and urban education at the Graduate Center. He recalls telling her that CHEST was toxic and that Parsons was mistreating students. (Fine said the student did not tell her about the cocaine.)

The student told Fine about “the environment, the language, the treatment of staff, the treatment of ‘subjects’ in studies,” she said. “Nobody brought me a sexual-harassment grievance. The kind of thing that came out at the very end, that is not the story I had heard. Although nobody was surprised.”

Fine and a former faculty colleague, Suzanne C. Ouellette, had heard from multiple students that there were problems at CHEST — and they felt a duty to do something about it, they said. Together, they related these concerns in person to Maureen O’Connor, who was then executive officer of the psychology program, and Tracey A. Revenson, who was the deputy executive officer, the professors said. Fine said she also contacted a faculty member from Hunter’s committee on sexual-harassment awareness, whose name she could not recall.

The director is toxic AF. Like, a straight up bully.

O’Connor, who is now president of Palo Alto University, said in an email that she had “no memory of a specific meeting” with the two professors about Parsons. Revenson, in an email, said she had “no recollection of a formal meeting” with the professors, adding, “in fact, my role did not include handling student concerns.” As faculty colleagues, Revenson said, she and Fine had “had many informal conversations” about students. Ouellette said that she recalled the conversation about Parsons as “informal.” There was no mistaking, however, that the two professors were concerned about the experiences students were having at CHEST, they said.

“Suzanne and I were seen as making trouble,” Fine said. “There was a tension around what I would now call whistle-blowing.”

Until 2018, in the fallout of CHESTFest, no administrator or human-resources official ever contacted the graduate student to talk about his experience, he said. If they had, they would have gotten an earful. By leaving CHEST, the student lost the financial support that had come with the position, forcing him to teach more classes to make ends meet and stalling his academic progress.

“My life became 500 percent harder,” the student said. “I’m probably going to be in debt for the rest of my life thanks to Jeff, because it was either student loans or be homeless.”

Parsons had secured for the occasion a posh private room surrounded by glass walls that peered into the restaurant’s high-end wine collection. The director ordered for himself and another CHEST colleague an expensive bottle of red wine, Bimbi recalls, admonishing Bimbi when he poured himself a glass of it.

The money that flowed into CHEST came from federal grants, notably the National Institutes of Health, which has strict rules prohibiting the use of grant money for purchasing alcohol. In light of that, CHEST colleagues assumed he had another source of revenue from which to draw for his parties. Multiple CHEST sources said Parsons had boasted of having an unrestricted “slush fund” or “lush fund,” which he said had been approved by Jennifer J. Raab, the president of Hunter College. When the Del Frisco’s check arrived that night, Bimbi said, Parsons laughed and pronounced: “Thank you, Jennifer Raab.”

A CUNY spokesman said that, “in his role as director of CHEST, Parsons was able to submit receipts to get reimbursed for appropriate expenses, including alcohol, from a Hunter College expense account.” Parsons “did not submit receipts nor was he reimbursed” for the 2011 dinner, CHESTfest 2018, or the booze cruise the year prior, the spokesman said.

Asked if Raab had approved the creation of the expense account for Parsons, the spokesman said that program leaders “normally go to the college provost and/or the president” to establish such accounts.

Raab was not made available for an interview.

As the dinner at Del Frisco’s was coming to a close, Parsons began cajoling the woman with whom he had shared the bottle of wine, directing her to press her breasts against the glass wall of the private room, several attendees said. “Come on, flash your tits,” Bimbi recalls Parsons saying.

The woman complied.

Another woman, a former CHEST employee, said she was so upset by Parsons that she got up and left. She understands, she said, why the other woman had agreed to expose her breasts. Moment to moment, people at CHEST did what they had to do to get through it.

“You have to find a way to go along with it — and you might even try to convince yourself, ‘We’re all just having fun here,’” the former employee said. “I think that happened to me as well.”

The incident at the dinner, the former employee continued, highlighted the complicated power dynamics that allowed Parsons to manipulate subordinates. “Jeff is gay. He’s not trying to have sex with me or sex with this woman,” the former employee said. “But that’s not what sexual harassment is. It’s an abuse of power.”

A third person who attended the dinner confirmed that he had also witnessed the incident. (The woman who was pressured that night declined interview requests, saying in an email, “I have moved on with my life.”)

There is no indication anyone reported the incident, and that’s not surprising to Bimbi. Crossing Parsons could be disastrous for a person’s career, particularly for graduate students, Bimbi said, who needed Parsons’s blessing to use data collected at CHEST.

“If he fired you, you lost your dissertation,” said Bimbi, who is now a professor of health sciences at LaGuardia Community College. “This is the culture: I can’t say a fucking word.”

But that was about to change.

The first complainant was Aaron S. Breslow, who had joined CHEST in 2010 as a research assistant. Like others who were looking to advance at CHEST, Breslow knew that the surest way to get ahead was to drink with Parsons. The best opportunity to do that was at one of the small pre-parties held in Parsons’s office before the full staff left for a CHESTFest or a happy hour, Breslow said.

“He would be behind his enormous desk,” Breslow said, “and everyone else would be on the other side of the desk, drinking mostly tequila and probably vodka. He would talk about which employees he liked and which he didn’t. He would ask for personal details about employees.”

“If you wanted a drink, you needed to approach his desk,” Breslow added. “He would pour shots for people. It was all about power.”

Breslow quit CHEST in 2013. Before he left, he reported his concerns to the CUNY research foundation’s human-resources department, he said. Among other things, Breslow said, he described “a pervasive culture of harassment, and a sexually hostile work environment.” He mentioned that the workplace was particularly hostile toward transgender people, telling officials that Parsons had once referred to a transgender staff member as “a man in a skirt.”

In the coming months, at least two other departing CHEST employees complained to the foundation’s human-resources department. One of them was William Mellman, who resigned in January 2014 from his position as a project manager. Mellman complained about a toxic culture at CHEST, noting in particular his ethical concerns about the center’s failures to protect employee privacy related to gender identity and HIV status. In response, foundation officials suggested he talk things out with Parsons, Mellman said. “It was as if they wanted us to shake hands and move on.”

He would pour shots for people. It was all about power.

The foundation’s human-resources department then heard from Jarad Ringer, who had been CHEST’s director of education and training. Ringer was surprised, he said, to hear employees talk openly at the center about their own drug use and their partying with Parsons. He noticed, too, that Parsons would make comments about staff members’ butts and say things like, “I wonder who he’s having sex with.” After less than a year on the job, in October 2014, Ringer had grown so frustrated with CHEST that he stormed out of a senior staff meeting that had turned contentious. (Ringer’s supervisor soon told him that he would not be welcome back at the center.)

Parsons was not present at the meeting, but one of Ringer’s colleagues texted the director afterward. Ringer had said “he felt attacked, that he felt unsafe, that CHEST was bullshit, and he was going home,” the colleague reported. Ringer, the colleague added, was “unhinged,” saying that he was going to the foundation “to complain about the leadership here at CHEST.”

Nothing in the communications, which were provided to The Chronicle in response to a public-records request, suggests there was concern for Ringer. Rather, he was described as a threat. Parsons’s immediate reaction was to suggest that the office locks be changed. Another person who was present at the meeting said that Ringer’s behavior was “shocking” and that she did not “feel safe” around him, a document shows.

When Ringer contacted human resources by phone, he said, “They told me there had been multiple complaints about Jeff.” But Ringer’s concerns appeared to go nowhere. “I definitely felt like I was being dismissed,” he said, “and I was pissed.”

None of the three complainants were followed up with, they said. Wendy Patitucci, the foundation’s senior director of human resources, did not respond to interview requests.

In addition to Breslow, Mellman, and Ringer, a former CHEST administrator told The Chronicle that, in the last four years of his employment, he had met informally a couple of times a year with the foundation’s human-resources department, describing the center as a toxic workplace. The former administrator, who never filed a formal complaint, choked up as he talked about the missed opportunities to rein in Parsons.

“I’m sorry,” he said in a cracking voice. “It’s still extremely emotional for me. When I first heard what happened at that CHESTFest I broke down in tears. … Even though I didn’t know the people involved, I felt responsibility. I would be happy to never hear his name again.”

As complaints appeared to fall on deaf ears, a pervasive sense grew at CHEST that there was no point in bothering to report anything.

“RFCUNY was the team of enablers that propped up Parsons, absolutely,” Breslow said. “We needed them to step in and they refused to.”

By 2014, there was mounting evidence something was seriously wrong at CHEST. A couple of years after, though, Hunter College was toasting Parsons’s success in a sacred space. In 2016 CHEST celebrated its 20th anniversary at Roosevelt House, home to Hunter’s public-policy institute. Raab, the college’s president, praised Parsons at the time for “brilliantly and passionately” guiding the center, saying, “We salute him with great admiration.”

Dressed in a dark suit and pinkish tie, Parsons described CHEST’s evolution from a fledgling center to a research behemoth that had raked in $55 million in grants. The secret of that success, Parsons said, was CHEST’s mantra: “Sex positive, no judgments.”

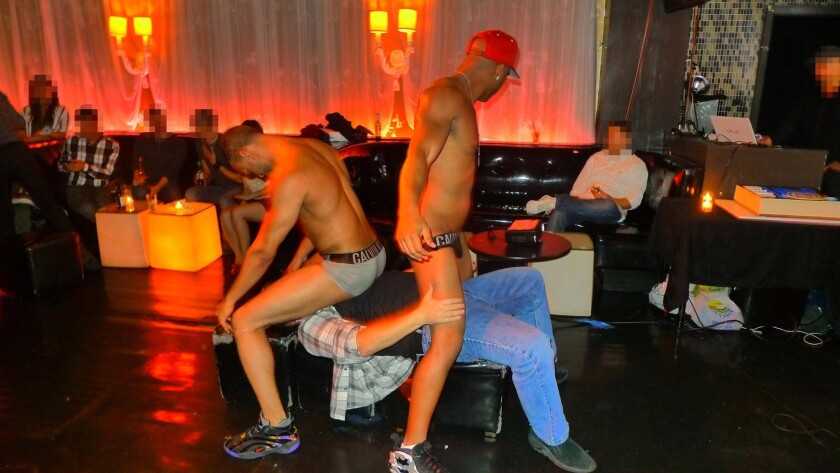

Three nights later, at Elmo, a popular restaurant and bar in Chelsea, CHEST gathered for a decidedly less restrained celebration. Photos from the event, provided to The Chronicle by a CHEST source, show employees looking on as Parsons lies on a bench with a bare-chested dancer in briefs grinding on his face, as another works on his lap. Another photo shows Parsons, martini glass in hand, his mouth agape over a fleshy dildo.

Photo provided by an anonymous source to The Chronicle

What Parsons did in his private life was his business. But CHEST events, which employees felt obligated to attend, eviscerated any line between Parsons’s role as the center’s director and his party-boy persona. Anyone who worked long enough at CHEST was likely to be summoned to watch the boss at a sexualized, alcohol-fueled work event.

Throughout the night at Elmo, photos from the center’s history were projected onto a screen, attendees said. Contained in the slideshow were the two faces of CHEST. In one photo, Parsons stood alongside Hunter’s president for a ceremonial ribbon-cutting in front of the center’s new facility near Penn Station. In another, Parsons, dressed in drag, gleefully gripped a stripper’s penis.

That didn’t work.

The following evening, a Saturday, Parsons sent an apology to CHEST staff members. “I want to say how incredibly sorry I am for what happened last night,” Parsons wrote. “My behavior took what should have been a celebration of the wonderful work we do and created an uncomfortable environment for everyone.”

“CHEST is not made great by me, it’s made great by all of you working hard on important aspects of our research,” he continued. “I will work to try and regain your trust, but I realize that will take time.”

Prior to sending the email to all of CHEST’s employees, Parsons had sent a draft version of the apology to someone else whose name the university redacted in documents provided to The Chronicle. In the subject line of the email, Parsons had written, “Is this enough?”

It wasn’t.

CHEST employees mobilized against Parsons, making a collective case to rid the center of its director and forcing action from administrators who time and again had left him unchecked. The fallout, which had been building since that fateful Friday night, kicked into overdrive the following week, documents show. The center’s employees filed complaints, and some met with John Rose, Hunter’s dean of diversity and compliance; and Patitucci, the human-resources director at the foundation. Employees were “traumatized,” they wrote in a complaint, by having witnessed a coworker “casually humiliated, harassed, and bullied” by Parsons.

A few days after CHESTFest, Parsons had told a colleague that “what they are saying simply did not happen,” documents show. But there is evidence Parsons was heavily intoxicated at the party. Days after the event, Parsons’s husband, Christopher Hietikko-Parsons, told a CHEST employee that Parsons had “blacked out” after the party and remembered nothing of the night, documents provided in response to a public-records request show. In one of Parsons’s own text messages from the evening, he wrote that he was “too drunk to read” a work-related text. He added that he “may go blow [redacted] in the bathroom.”

Yet as the walls were closing in on Parsons, he maintained that he would return to his post after a yearlong sabbatical. He believed this, he told colleagues, because he had the backing of Raab, Hunter’s president. She had told him as much in person, Parsons said. On Wednesday, May 9, 2018, days after Parsons’s transgressions had been reported to Hunter officials, Parsons was granted an audience with Raab, he told a colleague.

“Jeff said that Jennifer had assured him that he would be able to return after his sabbatical,” a CHEST employee wrote in a detailed account of the days after CHESTFest. “He said that she told him that ‘he can say he’s stepping down but that in her mind, he’ll always be at CHEST.’”

CUNY

Raab did not respond to numerous interview requests or specific questions sent to her public-relations representative. Hunter College, citing privacy exemptions in New York State’s public-records statutes, refused to provide records of communications Raab may have had with Parsons. In response to a request for any records of the president’s meeting with Parsons, Hunter College said none exist.

Buoyed by what he described as the president’s full support, Parsons privately lobbied four of his lieutenants to help perpetuate the narrative that he wasn’t going anywhere. “I’m not leaving,” Parsons wrote in a private Slack channel. Doing so, Parsons reminded them, would be devastating to the center and its employees. Grants tied to Parsons’s projects provided “64% of the funding to CHEST,” he wrote. “If I leave, 6 out of 10 jobs are lost.”

Parsons complained, too, of a “mob mentality” at the center, where anyone who dared to support him was ostracized. “Not everyone is on the same page about what a demon I am.”

Word spread at CHEST that Parsons, who had evaded accountability for so long, still appeared to have the support of Hunter’s president. Intentionally or not, Raab’s meeting with Parsons had lent credence to the notion that he remained untouchable. “That put the wind out of our sails,” a former employee said. “He was laying it down: ‘Don’t even try.’”

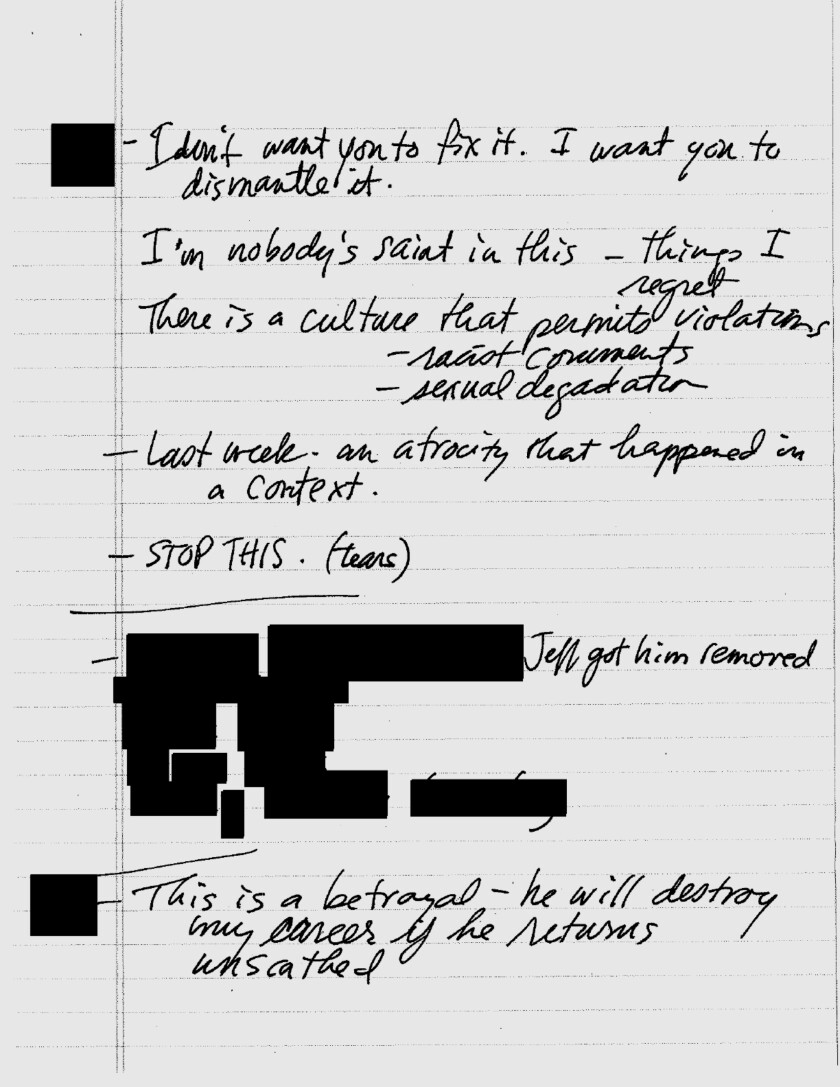

“I don’t want you to fix it,” one employee told officials. “I want you to dismantle it.”

Still, employees said they feared that Parsons would go unpunished. And what then? What would happen to those who had come forward? “This is a betrayal,” the employee said. “He will destroy my career if he returns unscathed.”

CUNY

In handwritten notes of the interview, an investigator recorded the employee’s plea: “STOP THIS. (tears).”

Days into the investigation, Patitucci, the foundation’s human-resources director, was forwarded an email from a faculty member in Hunter’s psychology department who said that “there is a long history of documented abuse” by Parsons at the Graduate Center “that has largely been ignored.” Forwarding the email to two high-level foundation officials, Patitucci wrote, “The pile grows.”

On May 17, 2018, nearly two weeks after CHESTFest, Parsons was placed on paid administrative leave as the center’s director, and, a few days later, as a distinguished professor. The center’s deputy director, Thomas Borkowski, and CHEST’s operations director, Carlos Ponton, were also placed on leave.

As the scope of the problem came into view, the foundation and CUNY hired an outside investigator to examine the allegations. It would fall to Debora L. Osgood, a former national enforcement director for the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, to sift through the sordid history that was now bubbling furiously to the surface.

In the course of Osgood’s inquiry, a host of information crossed the transom that raised questions about the apparent lack of oversight that had preceded this moment. Complaints brought to officials had appeared to go nowhere. Evidence, including photographs of wild CHEST gatherings posted on Facebook, had been hiding in plain sight.

At one point in Osgood’s investigation, she and Patitucci discussed a search for records of complaints from six different former CHEST employees. Patitucci knew of two such cases, she said, but noted that the foundation had, for several years, a “policy of purging emails every year.”

Seven years before the investigation, a professor from Fordham University had caught wind of problems at the center. David Marcotte, a Jesuit priest and clinical psychologist at Fordham, had developed an intervention for HIV-positive substance users that was being tested at CHEST. In 2011 a person working on the study quit, citing “extreme problems” with CHEST employees drinking in the office in the presence of research participants, documents show. In a brief interview with The Chronicle, Marcotte said, “Students were concerned. I do remember them talking to me.” Marcotte said that speaking any further about CHEST would be “a little dicey,” and he did not respond to a follow-up email asking if he had ever reported the problems to anyone.

Valerie Chiang for The Chronicle, photos from Getty Images

Complainants who came forward after CHESTFest 2018 also made “allegations related to financial improprieties at CHEST including the improper use of funds provided by CUNY and through federal grants,” according to a July 19, 2018, letter from the research foundation outlining the investigative process. But foundation officials stressed that these matters were not within the scope of Osgood’s investigation. Still, some documents compiled during the investigation focus on money.

In one interview, an employee said that the Stonewall event had been “charged to one of Jeff’s accounts that allows for alcohol use.” (An investigator, in handwritten notes, placed an asterisk next to this information.)

Other documents provided to The Chronicle give a snapshot of Parsons’s travel and expenses. Over 10 ½ months in 2012-13, Parsons spent $52,234.62 on 14 trips to conferences and meetings, records show. Six of those trips happened in June and July 2013, when Parsons visited Miami; San Diego; Lisbon; San Juan, Puerto Rico; Paris; and Honolulu.

Over the course of a single month, in July 2017, Parsons charged $4,105.50 to a purchasing card, records indicate. Included in the expenses are $1,131.81 for an iPad Pro in gold; $227.43 for transportation around Paris; and an $11.99 charge for Hulu, which is described in an attached receipt as “videos for research.” In that same month, Parsons’s AT&T bill included a charge of $944.76 for an iPhone 7 in gold.

None of the records establish evidence of misconduct. Asked if CUNY had found that Parsons had inappropriately used any money, a CUNY spokesman said in an email, “No investigation has identified the source of any funds that he may have misappropriated.”

Lichtman, Parsons’s lawyer, responded with a statement. “CUNY’s word salad response signifies nothing,” he wrote, “and the lack of any criminal investigation into Dr. Parsons signifies everything. What CUNY should be saying is the simple truth: no financial misconduct occurred here.”

We needed them to step in and they refused to.

Several former employees who spoke to The Chronicle questioned the propriety of CHEST’s business relationship with Mindful Designs, a video-production company owned by Parsons’s husband. From 2011 to 2018, the company was paid $656,000, or an average of $82,000 a year, the New York Post previously reported. A CUNY spokesman told the newspaper that the Mindful Designs arrangement had been cleared by a conflict-of-interest panel. Documents provided to The Chronicle show that, in 2018, Jeffrey Slonim, the research foundation’s chief counsel and board secretary, signed off on two independent contractor’s agreements with Mindful Designs totaling $210,000. (The second agreement was signed just four days before CHESTFest.)

Osgood’s investigation unfolded over about a year, drawing on witnesses, documents, photos, and videos. Taken together, Osgood concluded, the preponderance of the evidence supported a finding that it was more likely than not that Parsons had violated multiple policies, including CUNY’s drug-and-alcohol policy and its sexual-harassment policy. Parsons was also found to have engaged in “unprofessional conduct.”

As for the deputy director, Borkowski, Osgood found he had more likely than not subjected employees to unfair or improper treatment. Records related to Ponton, the director of operations, were not provided to The Chronicle. (Neither Borkowski nor Ponton are still working for the research foundation, according to CUNY officials. Efforts to reach the two men were unsuccessful.)

Publicly, CUNY has said little about the investigation, acknowledging nothing about the university’s own breakdowns in oversight. On July 12, 2019, Félix V. Matos Rodríguez, CUNY’s chancellor, announced that Parsons had resigned when faced with disciplinary proceedings aimed at his termination. The chancellor added that, going forward, “Avenues for reporting potential misconduct have been reinforced and clarified with the staff.” Matos Rodriguez commended the employees who had come forward, urging others to report misconduct “so we can take appropriate and prompt action.”

Provided with The Chronicle’s findings, a CUNY spokesman said in an email on Tuesday that the university had responded swiftly “when CHEST employees brought Dr. Parsons’ reprehensible behavior to Hunter officials.” Since Parsons’s departure, the spokesman wrote, “the university and its Board of Trustees have taken substantial measures to prevent similarly toxic situations; to make sure that all members of the CUNY community are aware of their rights and how to report sexual misconduct; and to train all those responsible for receiving those complaints how to handle them with speed and sensitivity.”

“We are grateful,” the spokesman added, “for the courage of the staff members and students who came forward and put an end to Parsons’ behavior.”

The kind of accountability that many at CHEST had hoped for remains elusive: Who was responsible for letting this happen? If Osgood’s investigation found an answer, CUNY chose not to share it with those who had united against Parsons and forced the administration to act. Even now, the university won’t do that. Citing attorney-client privilege, CUNY denied The Chronicle’s public records requests for Osgood’s final report. Ironically, the credentials that had made Osgood seem unimpeachable — an outside lawyer following the evidence — have also served to ensure that the full breadth of her findings and conclusions will probably never see the light of day. (Osgood declined an interview request.)

What’s happened at CUNY fits into a larger national pattern. As survivors of sexual abuse and misconduct demand more institutional accountability, colleges have leaned on attorney-client privilege to keep records under wraps. Five years after Larry Nassar, a former Michigan State University sports doctor, was publicly accused of sexual abuse, the university’s Board of Trustees has continued to resist calls to waive privilege and release all relevant records.

In sexual-misconduct cases, it is “standard operating procedure” for universities and other organizations to evade accountability by invoking attorney-client privilege, said Rachael Denhollander, a lawyer and Nassar’s first public accuser. This ensures that the focus remains on the abuser, and not the organization in which he operated, she said. When survivors realize that the use of an outside lawyer means they’ll never know the full truth, they experience “compounding trauma,” Denhollander said. “What that means is it’s not just your abuser you can’t trust,” she said; “it’s everybody around you, you cannot trust.”

Behind the scenes, CUNY and Parsons quietly agreed, in 2019, to legal settlements totaling $1.4 million with people who had worked at CHEST, documents show. On April 30, 2019, a couple of months before CUNY’s chancellor announced Parsons’s resignation, CUNY and Parsons agreed to pay a total of $425,000 in a settlement with a CHEST employee. (Of that sum, $75,000 came from Parsons.) On September 3, 2019, CUNY, Parsons, and Parsons’s husband settled for $975,000 with five current or former CHEST employees. (Parsons and his husband agreed to pay $75,000 of that total, allocated in equal parts to three of the claimants.) In both settlements, about a third of the money went to lawyers representing the claimants.

Both agreements contain a key stipulation: The claimants can never suggest to “any person” that Parsons or CUNY have ever admitted to doing anything wrong.

[ad_2]

Source link